Hine's emerald facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Hine's emerald |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Female Hine's emerald | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Odonata |

| Infraorder: | Anisoptera |

| Family: | Corduliidae |

| Genus: | Somatochlora |

| Species: |

S. hineana

|

| Binomial name | |

| Somatochlora hineana Williamson, 1931

|

|

|

|

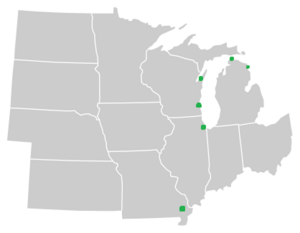

| Current US range, one additional population is present in Ontario | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The Hine's emerald (Somatochlora hineana) is a special dragonfly that needs protection. It lives in parts of the United States and Canada. You can find them in Illinois, Michigan, Missouri, Ontario, and Wisconsin.

Baby Hine's emeralds, called larvae, live in shallow, moving water. They like fens (wetlands with lots of minerals) and marshes (wetlands with grassy plants). They often hide in crayfish burrows. The biggest dangers to this dragonfly are losing their homes or their homes changing. Because of this, the Hine's emerald is protected by law in both the United States and Canada.

Contents

What Does the Hine's Emerald Look Like?

The Hine's emerald dragonfly changes how it looks throughout its life. When they are young, called nymphs, they look like other baby dragonflies. A fully grown nymph is about 0.9 inches (2.3 cm) long.

Adult Hine's emeralds have special features that make them unique. They have a dark-green body section called a thorax with two yellow stripes on the sides. Their eyes are brown for the first few days after they become adults. After about three days, their eyes turn a bright emerald green. Their wings are clear with a little amber color near the body. As they get very old, their wings become smoky.

An average adult Hine's emerald is about 2.5 inches (6.4 cm) long. Their wingspan (how wide they are with wings spread) is about 3.5 inches (8.9 cm). Female dragonflies are usually a little longer than males.

Hine's Emerald Life Cycle

Hine's emeralds go through three main stages: egg, larva, and adult. Both the egg and larval stages happen in water. These dragonflies spend most of their lives as larvae, which can last 2 to 4 years. How long this stage lasts depends on how much food they have, how deep the water is, and the temperature.

While they are larvae, they live in small streams. They grow by shedding their skin many times, a process called molting. When a larva is ready to become an adult, it climbs onto a plant like a cattail. It then sheds its skin one last time. The adult dragonfly comes out of the old skin and flies away.

Nymphs usually become adults in June and July. About the same number of male and female nymphs turn into adults. The adult stage lasts for 4 to 6 weeks and has three parts:

- Pre-reproductive stage (before they can have babies)

- Reproductive stage (when they have babies)

- Post-reproductive stage (after they have babies)

During these stages, adults hunt for food, claim their areas, and have babies. Overall, Hine's emerald dragonflies live for 2 to 4 years.

Reproduction

Before they can have babies, a male dragonfly must find and claim an area. These areas are about 2–4 metres (6.6–13.1 ft) wide and are close to water. Male dragonflies fly around these spots and protect them from other dragonflies.

A female starts the mating process by flying into a male's area. The male will then chase her. Once he catches her, he holds onto her body. They then fly to nearby bushes, and mating begins. After mating, the female dips her tail into shallow water many times to lay her fertilized eggs. Hine's emeralds usually have babies once and then die soon after. They reproduce in June, July, and August.

What Do Hine's Emeralds Eat?

Hine's emeralds are meat-eaters during both their larval and adult stages. Adult Hine's emeralds eat small flying insects like mosquitoes and gnats. They usually hunt while flying, especially along the edges of forests. These forest edges are often next to roads.

During the pre-reproductive stage, their hunting flights last 1 to 3 minutes. During the reproductive stage, these flights can last up to 15 minutes. Dragonflies ready to reproduce might fly up to 1.2 miles (1.9 km) during these hunts. Sometimes, many adult dragonflies hunt together in large groups. Hunting in groups might help protect them from animals that want to eat them.

Baby Hine's emeralds (nymphs) hunt at night. They eat other water-dwelling larvae, like those of mosquitoes or mayflies. Scientists think that nymphs might eat different kinds of prey as they grow. When hunting, nymphs stay very still and wait for their prey to come close.

Where Do Hine's Emeralds Live?

Hine's emeralds live in different wet places like wetlands, ponds, wet meadows, forests, and marshes. All these places have some important things in common:

- They have slow-moving streams with lots of minerals.

- They have both open areas for hunting and wooded areas for resting.

- They have crayfish burrows, which baby dragonflies use for shelter.

- They have exposed or slightly covered bedrock (rocky ground).

- They have paths like roads, forest clearings, streams, and railroads that help dragonflies move around.

Other things about their homes, like the types of plants, can be different in various regions.

Today, Hine's emeralds live in parts of the United States (Illinois, Michigan, Missouri, Wisconsin) and Canada (Ontario). In the past, they also lived in Ohio, Indiana, and Alabama. But because their homes have changed so much, they probably don't live in those states anymore. We don't know if they ever lived in other states.

The first time Hine's emerald dragonflies were described was in 1931 near Indian Lake in Ohio. The IUCN Red List says there are 47 known places where Hine's emeralds live. This includes Ontario, Canada, and the US states of Illinois, Michigan, Missouri, and Wisconsin.

Hine's Emerald Ecology

Several animals eat Hine's emeralds. Crayfish, turtles, amphibians, and other water animals eat the nymphs. Spiders, frogs, birds, and large dragonflies eat the adults.

Some of these predator-prey relationships might actually help the Hine's emeralds. A study from 2006 suggests that devil crayfish (Lacunicambarus diogenes) help Hine's emerald nymphs survive. When Hine's emerald habitats dry up in late summer, crayfish burrows stay wet. By living in these burrows, the nymphs have a better chance of surviving dry periods. It's not known if Hine's emeralds have similar helpful relationships with other animals.

How Many Hine's Emeralds Are There?

We don't have much information about how many Hine's emerald dragonflies there were in the past. The IUCN Red List says that current numbers are steady, with an estimate of over 30,000 dragonflies worldwide. As of 2013, the population in Door County, Wisconsin is the largest and most important, with as many as 20,000 individuals.

In the United States, there are two main recovery groups: the Northern Recovery Unit and the Southern Recovery Unit. The Northern group has two populations: Northern Wisconsin and Michigan. The Southern group has four populations: Ozaukee County Wisconsin, Southwest Wisconsin, Illinois, and Missouri. Populations are considered unique if they are separated by at least 30 miles. This means there's a low chance of them mixing their genes.

These six populations are made up of 27 smaller groups. This means there are 69 total places where Hine's emeralds are found. Thirty-five of these places are fully protected, and 21 are partly protected. Eleven places are not protected, and we don't know the protection status of the last two. We are missing information on how many adult dragonflies are reproducing in many of these smaller groups. This makes it hard to know how well conservation efforts are working.

A review in 2013 suggested future actions to help conservation. One important step is to study how Hine's emerald populations change over time. More information is also needed about key population details, like the smallest possible population sizes and current numbers. It's also important to study the genetic differences between populations. Helping Hine's emeralds reach stable population sizes would allow them to be moved from "endangered" to "threatened" on the Endangered Species Act list. To do this, up-to-date population data is very important.

Protecting the Hine's Emerald

Conservation Status

The Hine's emerald dragonfly was first suggested as an endangered species in October 1993. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service said there were three main reasons why it needed federal protection. Its homes were broken up, and its populations were small and spread out. By January 1995, the Hine's emerald was officially added to the Endangered Species Act (ESA) as an endangered species. When it was last checked in 2008, it was the only dragonfly species on the Endangered Species Act list.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service published a plan to help the species recover in 2001. The main goal was to bring the dragonfly back to healthy population numbers. The plan created the Northern and Southern Recovery Units. To be moved to a less serious status on the Endangered Species Act, certain goals must be met. Each Recovery Unit needs at least three smaller groups with 500 reproducing adults for at least 10 years. Also, there must be two breeding sites for each smaller group. These areas must have federally protected homes.

The Fish and Wildlife Service suggested many ideas to help Hine's emeralds survive. This includes protecting water areas and limiting land use. Buying land and creating nature preserves are also ways to protect the species. They also stressed the importance of managing existing populations and studying how they change. To do this, they need to look for new Hine's emerald populations and create education programs. The plan's goal is clear: "make sure the Hine's emerald populations can survive long-term by stopping or reversing their decline and dealing with what threatens them."

In a 2013 review, four main goals for changing the species' status were listed:

- Each Recovery Unit must meet the population goals from the first plan. As of 2013, some Northern Recovery Unit populations were doing well, but no Southern Recovery Unit populations had met this goal.

- There must be at least two breeding homes for each smaller group. Each breeding home must get water from different sources. As of 2013, this goal had not been met, and only 12 of 27 smaller groups had more than one breeding site.

- The homes that support these smaller groups must be officially protected and managed. This includes controlling plants and animals that don't belong there and restoring local water sources. Actions to reduce cars in the area are also suggested.

- A plan to monitor each population must be created. This plan needs to include yearly estimates of how many dragonflies there are. This last goal has not been met because we don't know enough about their breeding and home structures. Many areas lack the tools needed to check population sites.

In Canada, the Hine's emerald is listed as endangered under the Species at Risk Act since 2017. It seems to live in a small area in Ontario, mainly in the Minesing Wetlands. The dragonfly's survival is at risk due to city growth and the spread of unwanted plants like European common reed (Phragmites australis subsp. australis) and glossy buckthorn (Frangula alnus).

The Hine's emerald dragonfly was last checked by the IUCN Red List on June 8, 2018. At that time, it was listed as "Least Concern." This is different from the ESA's older classification of "Endangered."

Important Homes for Hine's Emeralds

The current important homes for Hine's emeralds cover 26,531 acres of land. This land is mostly in different counties in Illinois, Michigan, Missouri, and Wisconsin. The expected costs to protect this land are between $10.5 million and $25.2 million over 20 years. This plan for important homes was finalized in 2010. However, this plan is quite different from the first ideas and rulings.

Threats to Hine's Emeralds

The plan to help Hine's emerald dragonflies recover was published in 2001. At that time, the main dangers were losing or changing their homes and pollution. Hine's emeralds live in marshes and wetlands, which are already rare places. Losing more of these homes would harm the remaining dragonflies. The recovery plan explained that building new factories, farms, and businesses caused the most damage. This damage led to the species' decline.

A review in 2013 looked at more recent dangers. It listed common threats at many Hine's emerald sites. These threats include:

- Homes being broken into smaller pieces

- Changes to water flow

- Pollution

- Dragonflies being hit by vehicles

- Invasive animals and plants

Homes Breaking Apart

Hine's emerald dragonfly populations are at risk when their homes get broken into smaller pieces. As of 2012, studies were looking into things that block dragonfly movement, like roads and bridges. They wanted to see how these barriers affect how dragonflies fly and spread out. If Hine's emeralds cannot spread properly, it can lead to small, isolated groups. This also reduces their genetic diversity, which makes them weaker against other dangers.

Invasive Animals

Animals that are not native to an area can harm Hine's emerald homes. Beavers, wild hogs, and nine-banded armadillos are the main potential threats. They can damage the dragonflies' homes. Beaver dams can flood the wetlands where Hine's emeralds live. When wild hogs look for food, they can damage Hine's emerald habitats. As of 2013, wild hogs were only a threat in Missouri. However, their numbers have grown in other states where Hine's emeralds live. Armadillos also affect Hine's emerald homes when they dig for food. Armadillos dig up soil looking for insect larvae and also dig in burrows. The impact of armadillos on Hine's emerald homes will need to be watched as armadillos spread to new areas.

Invasive Plants

Plants that are not native can affect Hine's emerald homes, how they act, how they move, and where they have babies. Woody plants and cattails growing too much in Hine's emerald homes can affect how adult dragonflies fly. Invasive woody plants can also reduce the amount of water under the ground. This water is very important for baby Hine's emeralds. The spread of plants like the common reed might reduce crayfish numbers. This would mean fewer crayfish burrows for baby Hine's emeralds to hide in.

Human Impact

Humans can affect Hine's emerald dragonflies in many ways. Most human impact involves destroying or changing their homes. Reducing the size of their homes breaks up populations. Digging quarries, filling wetlands, and creating landfills are examples of harmful human actions.

Pollution is another way humans can harm Hine's emerald populations. Landfills can release harmful chemicals that pollute surface and groundwater. Both surface and groundwater are very important for Hine's emeralds when they are larvae. Fun activities and farming can also affect Hine's emerald populations. The bug killers, weed killers, and fertilizers used in these activities could harm the dragonflies. Fertilizers might also change Hine's emerald homes in ways that hurt the species.

Conservation Efforts

The Hine's emerald is on the Federal list of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants. This means the species is protected under the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (ESA). The Hine's emerald is also listed as endangered in Illinois, Wisconsin, Missouri, and Michigan. This gives the species protection at both the state and federal levels.

Protecting Their Homes

Many groups help protect Hine's emerald homes. State and County groups protect the homes of three smaller groups in Illinois. The University of Wisconsin and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR) help protect Hine's emerald homes, like the Gardner Swamp Wildlife Area. They protect the home of the population in Ozaukee County, Wisconsin. The WDNR also protects the home of the population in Southwest Wisconsin. The U.S. Forest Service or Missouri Department of Conservation protects Hine's emerald homes in Missouri. These groups protect most of the homes for two of the Missouri smaller groups. State and Federal groups protect homes in the Northern Recovery Unit. They protect the homes of five out of the 16 smaller groups.

Groundwater Protection

Areas where groundwater is refilled are very important for Hine's emerald homes. Researchers have worked to map the areas that supply water to many Hine's emerald homes. However, they have not mapped these areas for all Hine's emerald sites yet. More research is needed to find these areas for all sites. Sections 7 and 9 of the ESA protect all identified groundwater recharge areas. The Illinois Natural Areas Preservation Act protects identified areas in Illinois.

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |