History of Portugal (1834–1910) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kingdom of

Portugal and the Algarves Reino de Portugal e dos Algarves (Portuguese)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1834–1910 | |||||||||

|

Anthem: Hino da Carta

"Anthem of the Charter" |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Capital | Lisbon | ||||||||

| Common languages | Portuguese | ||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholic | ||||||||

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy | ||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||

|

• 1834–1853

|

Queen Maria II(first) | ||||||||

|

• 1908–1910

|

King Manuel II (last) | ||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||

|

• 1834–1835

|

Pedro de Holstein (first) | ||||||||

|

• 1910

|

António Teixeira (last) | ||||||||

| Legislature | Cortes Gerais | ||||||||

|

• Upper house

|

Chamber of Peers | ||||||||

|

• Lower house

|

Chamber of Deputies | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 26 July 1834 | |||||||||

|

• Lisbon Regicide

|

1 February 1908 | ||||||||

|

• Revolution of 1910

|

5 October 1910 | ||||||||

| Currency | Portuguese real | ||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | PT | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

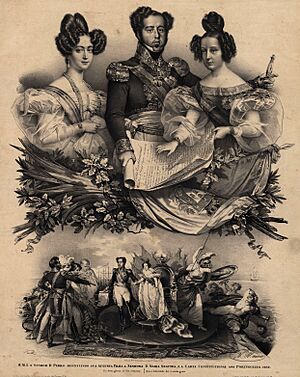

The Kingdom of Portugal was a country ruled by a king or queen from 1834 to 1910. This period started after a big conflict called the Liberal Civil War. The government was a constitutional monarchy, meaning the king or queen shared power with a parliament, following a set of rules called a constitution.

After the war, Portugal faced many changes. There were often new governments, and a new political party, the Portuguese Republican Party, grew stronger. People were unhappy with how the country was run. This was made worse when Britain demanded Portugal give up its plans to connect its colonies in Africa (today's Angola and Mozambique). This event, called the British Ultimatum, made many Portuguese feel humiliated.

Things got even more difficult when King Carlos I tried to rule more strictly. This led to his assassination in 1908. Finally, in 1910, a revolution ended the monarchy, and Portugal became a republic.

Contents

Political Challenges and Corruption

After the Civil War, different groups had different ideas about how Portugal should be governed. Some people called the government "Devourism" (Devorismo). This term meant that politicians were using public money for their own benefit, like a "gang made up to devour the country."

The government was often weak, and there wasn't a clear plan for the country. Military leaders sometimes got involved in politics. The young Queen Maria II became queen at just 15 years old. She wasn't ready to rule alone. Her advisors, who were mostly nobles, tried to use her power to stop the liberal changes.

There were two main political groups:

- Moderates: They supported the Constitutional Charter of 1828.

- Liberals: They wanted to bring back the more democratic Constitution of 1822.

Both groups were disorganized, and their ideas weren't very clear. Many politicians switched sides often. Most people in Portugal couldn't read or write, so they didn't have much say in politics. Education was mostly in cities, where merchants and government workers had more chances to improve their lives.

Economic Struggles

Portugal's economy struggled after the war. It still relied on farming and taxes from land. There wasn't enough money available for businesses to buy new machines or build factories. Because of this, the economy didn't grow much. Even in 1910, most workers were in small shops, not large factories.

Writers and thinkers, known as the "Generation of the 70s," wrote in newspapers about how to improve the economy. They looked at how countries like France and Britain were growing. Some, like Antero de Quental, even started thinking about socialism. They worried about rich people having too much power, people leaving rural areas, and poverty in cities. They also thought about social fairness and what the government should do to help its citizens.

Towards the end of the 1800s, Portugal's economy declined. This can even be seen in the average height of people. Portuguese people became shorter compared to other Europeans. This was because wages were low, and Portugal was slow to industrialize. Also, not enough money was spent on education, which meant people didn't get the skills needed for new industries.

New Laws and Reforms

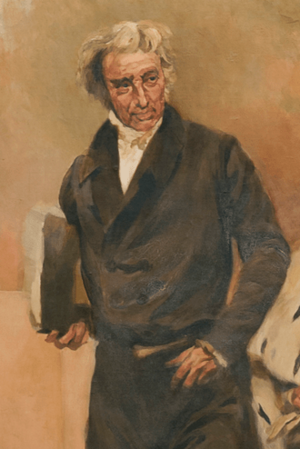

During the constitutional monarchy, many new laws were proposed. A key figure was Mouzinho da Silveira. He believed that politics should help improve people's lives and the economy. His ideas were later adopted by new politicians.

Some of his important changes included:

- Making taxes fairer.

- Ending tithes (payments to the church).

- Reducing taxes on exports.

- Stopping the government from controlling local trade.

- Separating the courts from government offices.

- Allowing more free trade and stopping some monopolies.

These changes aimed to reduce the special privileges of the wealthy, create more equality, boost the economy, and make the government work better.

Separating Church and State

In 1834, Joaquim António de Aguiar made a big change: he ended government support for religious groups and took control of their lands and buildings. This was called Mata-Frades (Killer of Brothers). The government hoped to sell these lands to poor people, but most couldn't afford them. Instead, rich people and land owners bought them.

Changing Local Government

Another change was how local areas were managed. There was a big debate about whether power should be centralized (controlled by the national government) or decentralized (controlled by local governments). In 1836, the government reduced the number of municipalities (local administrative areas) because many couldn't govern themselves well. This changed back and forth over the years. Eventually, local governments started getting financial help from the national government.

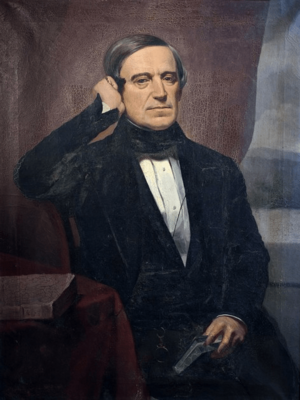

New Civil Code

For a long time, Portugal's laws were a mess. They were old and hard to understand. Many people knew they needed to be updated. In 1867, a new set of laws, called the Portuguese Civil Code, was created. It was based on the work of Judge António Luís de Seabra. This new code organized laws about people, property, and legal rights. It was used for a very long time, until 1967.

Political Conflicts: Setembrismo and Cartismo

For the first two years, the Constitutional Charter was the law. But the government and opposition couldn't agree. Queen Maria II changed the government four times and then called new elections. The opposition felt the Charter was causing problems and wanted to go back to the 1822 Liberal Constitution.

In September 1836, a revolution in Lisbon forced Queen Maria II to bring back the 1822 Constitution. The new government members were called Setembristas. This movement was a reaction to political instability. It was supported by the military and city dwellers, but constant demands from the public made it hard for the government to act.

The Queen tried to fight back, but her attempt failed. In 1837, military leaders tried to restore the Charter, but this "Revolt of the Marshals" also failed after many people died.

During their time in power, the Septembrists created public schools and art academies. They also expanded Portugal's colonies in Africa and banned slavery in 1836. They tried to unite the different political groups by creating a new Constitution in 1838, which was a compromise between the Chartists and the Septembrists.

In 1842, a politician named Costa Cabral led a takeover in Porto with the Queen's support. The Queen brought back the 1826 Charter. But there were still many disagreements. A military uprising in 1844 was put down, but Cabral's government struggled to control popular unrest.

Maria da Fonte Uprising

Many of Costa Cabral's new rules directly affected people in the countryside. He made local governments responsible for healthcare and finances, which felt like going back to old medieval systems. Two new rules, banning church burials and assessing land, worried rural people. They feared the government would take their land.

In April 1846, a revolt started in a village called Fontarcada. This uprising was called the Revolution of Maria da Fonte because women were very active in it. They carried weapons, burned land records, and even attacked a military group. Some rebels even supported the old king, Miguel, but mostly they just wanted to stop the government from taking their land and imposing taxes.

Unhappy politicians used this peasant uprising to attack Cabral's government. They forced him to leave the country. But the Queen then formed a new government with more loyal politicians.

Patuleia Civil War

The peasant uprising soon turned into a civil war called the Patuleia. It was a fight between the Septembrists and the Chartists. This war spread across the country. It was a mix of different groups, including Septembrists and supporters of the old king, who were all against the Cabralist politicians. The fighting was so bad that other countries like Great Britain and Spain had to step in to stop it. The war ended with the Chartists winning, and an agreement was signed in 1847 that offered forgiveness to the Septembrists.

Regeneration Period

After 1847, Portugal had a period of calm. Not much happened politically for a few years. Then, Marshal Saldanha, a military leader, started a revolt in 1851. Few people supported him at first, but eventually, he gained strong support in Porto. He called his movement "Regeneration," meaning a renewal of the political system. The Queen, worried about another civil war, brought him into the government.

Rotativism: Taking Turns in Power

This led to a period where the main political parties agreed to work together. The Constitution didn't change, but how the government worked did. Elections became more direct, and Parliament could investigate government actions. There was a lot of excitement for national unity. Costa Cabral went into exile again, and the country started a program to improve its infrastructure, like roads and railways.

The old Chartists and non-Chartists formed new parties: the Partido Regenerador (Regenerator Party) and the Partido Histórico (Historic Party). Later, the Septembrists formed the Partido Progressista (Progressive Party). The Regenerator and Historic parties were central parties that supported the monarchy and wanted to rebuild the economy. However, after 1868, there were still many political problems, and the focus on public works led to financial difficulties for the country.

This period of cooperation ended in 1868 due to financial problems and unrest. In 1870, Marshal Saldanha again took control with the army, trying to force political reforms.

In 1890, the British government gave Portugal an ultimatum. They demanded that Portugal remove its troops from parts of East and South Africa. Portugal had managed some of these territories for centuries. The Portuguese government had to agree, which made many people feel very humiliated and angry.

Assassination of King Carlos I

On February 1, 1908, King Carlos I and his family were returning to Lisbon. As their open carriage passed through a main square, two republican activists, Alfredo Luís da Costa and Manuel Buíça, shot at them. Manuel Buíça, a former army sergeant, fired five bullets. Three bullets hit and killed the king. Another bullet fatally wounded his oldest son, Luís Filipe, who was next in line for the throne. During the chaos, the police killed the two attackers and an innocent bystander. The carriage was rushed to a nearby building, where both the king and the prince were declared dead.

The king's youngest son, Manuel, quickly became the new King of Portugal. He was only 18 years old.

King Manuel II ruled for only a short time. Republican groups continued to attack the monarchy. Even though the young king was popular, his reign was difficult. He tried to be a good king and follow the rules of the constitutional monarchy. He was concerned about social issues, like helping the working class, but he didn't have much time to make big changes.

The 5 October 1910 Revolution

After elections in August 1910, the Republican party had only 14 representatives in the parliament. Even with support from other parties, they had far fewer seats than the pro-monarchy politicians. The governments during King Manuel II's reign were often unstable, and he changed the government seven times.

Militant Republicans and their allies, a secret society called the Carbonária, didn't want to wait any longer. Between October 4 and 5, 1910, members of the Carbonária, republican youth, and parts of the army started a takeover against the monarchy. The young king and his family managed to escape from their palace and went into exile in England.

On the morning of October 5, 1910, the Republic was declared from the balcony of Lisbon City Hall. This event ended eight centuries of monarchy in Portugal and began a new era for the country.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Portugal (1834-1910) para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Portugal (1834-1910) para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |