Hoodening facts for kids

Hoodening is a fun folk custom from Kent, a county in south-eastern England. It involves a special wooden hooden horse carried by someone hidden under a cloth. This tradition is a unique part of Kent's history.

Long ago, hoodening was mostly found in East Kent. But in the 1900s, it also spread to West Kent. It's like other "hooded animal" customs found across the British Isles.

From the 1700s to the early 1900s, farm workers performed hoodening around Christmas time. They formed teams with the hooden horse and visited local homes and shops. They expected a small payment for their performance. Today, this specific practice doesn't happen anymore. However, the hooden horse is now part of other Kentish folk traditions. These include Mummers' plays and Morris dances, which happen at different times of the year.

People still debate where the hoodening tradition came from. Some thought the name "hooden" was linked to an old god named Woden. But historians and folklorists don't think this is true. Most experts now believe "hooden" refers to the "hooded" cloth worn by the person carrying the horse. Similar customs like the Mari Lwyd in Wales or the Old Tup in northern England also exist. These traditions might have become popular in the 1500s and 1600s. This was when hobby horses were fashionable among rich people.

The first mention of hoodening in writing was in the 1700s. Over time, many thought the tradition was disappearing. In the early 1900s, a folklorist named Percy Maylam studied and wrote about it. He published his findings in a book called The Hooden Horse in 1909. After the First World War, the custom seemed to have ended. But it was brought back in a new way in the mid-1900s. The hooden horse then became part of modern Kentish folk traditions.

Contents

What is Hoodening?

Sources show that the hoodening tradition was quite similar across East Kent. Even though there were some small differences.

The Hooden Horse and Team

The main part of the custom was the hooden horse. It was usually a wooden horse's head on a pole about four feet long. The horse's jaw could move with a string. A person would carry the horse while hidden under a dark cloth.

A team of "hoodeners" would carry the horse through the streets. There were usually four to eight men in the team. This group included the person carrying the horse. There was also a "Groom" or "Driver" who led the horse with a whip. A "Jockey" would try to ride the horse. A "Mollie" was a man dressed as a woman. And one or two musicians would play music. All these men were farm workers, often those who worked with horses.

The Performance

The team performed the custom around Christmas time, often on Christmas Eve. They would arrive at people's houses and sing a song before being let inside. Once inside, the horse would prance and snap its jaw. The Jockey would try to ride it. The Mollie would sweep the floor with a broom and playfully chase any girls. Sometimes, they would sing more songs or carols. After getting paid, the team would leave to visit another house.

Where was Hoodening Found?

Historians have found records of 33 hoodening traditions in Kent before the 1900s. These were mostly along the eastern and northern coasts of the county. All of them were in East Kent, and the custom was not known in West Kent.

Why East Kent?

The folklorist Percy Maylam noticed that hoodening was not found west of Godmersham. This area was well-populated when the hoodeners were active. Maylam also noted that all the areas with the tradition used the East Kentish dialect. Another folklorist, E. C. Cawte, studied where hoodeners appeared. He found no clear reason why the custom didn't spread further.

Similar Customs in Britain

Hoodening was part of a bigger "hooded animal" tradition in Britain. These customs often shared similar features. They used a hobby horse and were performed around Christmas. They involved singing or speaking to ask for payment. And the team often included a man dressed in women's clothing.

- In South Wales, the Mari Lwyd tradition involved groups of men with a hobby horse visiting homes at Christmas.

- In parts of Derbyshire and Yorkshire, the Old Tup tradition featured groups carrying a hobby horse with a goat's head. They also visited homes around Christmas.

- The folklorist Christina Hole saw links between hoodening and the Christmas Bull tradition in Dorset and Gloucestershire.

- In south-west England, there are two hobby horse traditions: the Padstow 'Obby 'Oss festival and Minehead Hobby Horse. But these happen on May Day, not at Christmas.

The exact origins of these traditions are not fully known. But since there are no mentions of them from the late Middle Ages, they might have come from the popularity of hobby horses in the 1500s and 1600s. This is similar to how Morris dances became popular across England before developing into regional styles.

What Does "Hooden" Mean?

Percy Maylam noted that in the 1800s, people often spelled the word as hoden. But he preferred hooden because it sounded more like the way people said it. He said "hooden" rhymes with "wooden." The hoodeners he spoke to didn't know what the word meant or where the tradition came from.

Possible Meanings

The word hoodening has an unknown origin.

- One idea is that hooden came from a mispronunciation of wooden. This would refer to the wooden horse. Maylam didn't think this was likely for the Kentish dialect.

- Another idea is that hooden refers to the "hooded" cloth worn by the person carrying the horse. Historian Ronald Hutton thought this was the "simplest" explanation. Folklorists Cawte and Charlotte Sophia Burne also thought it was the most likely. Maylam disagreed, saying the cloth was too big to be called a hood.

An old writer named Alfred John Dunkin thought Hodening came from Hobening. He linked it to the Gothic word hopp, meaning horse. Maylam thought this idea could be ignored.

Maylam also thought hoodening was a changed version of a Morris dance. He suggested it might have been linked to the folk hero Robin Hood. But others disagreed. They pointed out that Robin Hood was an archer, not a horse rider. Also, Robin Hood games happened in May, not at Christmas.

Early Medieval Origins?

In 1807, someone suggested that hoden was linked to the Anglo-Saxon god Woden. They thought the tradition might be a leftover from a festival for Saxon ancestors. In 1891, it was suggested the custom was once called "Odining," after the god Odin.

Maylam was interested in the idea that hodening came from Woden. But he found no strong proof for it. He noted that the "W" in "Woden" likely wouldn't be lost in the Kentish dialect. For example, the village Woodnesborough keeps its "W." Both Burne and Cawte also thought linking the tradition to Woden was unlikely.

Folklorist Geoff Doel thought hoodening might be much older than its first written mentions. He suggested it could be a Midwinter ritual to help plants grow. He noted that other English winter customs, like the Apple Wassail, are seen this way. He also wondered if the horse in the tradition was linked to the white horse symbol of Kent. Or to Hengest and Horsa, who are important in Kent's early history. However, the white horse became a symbol of Kent much later, in the 1700s. So, any old link to hoodening is probably not true.

Hoodening in the Past

Late 1800s Sightings

Many years later, a Kentish writer named J. Meadows Cooper said he saw a hooden horse party in a pub near Margate on Boxing Day in 1855. Another local, Mrs. Edward Tomlin, remembered the hooden horse visiting her home near Margate at Christmas from the 1850s to 1865.

Percy Maylam also found stories of hooden horses in Herne and Swalecliffe. These stopped in the 1860s. Another was active from Wingate Farm House in Harbledown in the 1850s. And one at Evington had stopped by the 1860s. He found another at Lower Hardres that was active from the 1850s until 1892.

In 1868, a newspaper mentioned hoodening in Minster, Swale on Christmas Eve 1867. The writer was surprised, thinking the horse was "extinct."

In 1888, a book about the Kentish dialect mentioned Hodening as carol singing. But it said Hoodening used to be a "masquerade" with the hooden horse. They learned this from a farmer who used to send a horse around. Later, a man would pretend to be the horse with a wooden head. The authors thought the custom had stopped. But Maylam believed this was wrong. He said hoodeners were still active in St Nicholas-at-Wade in the early 1900s. Locals remembered it happening there since the 1840s.

In 1889, a letter from Charles J. H. Saunders appeared in a newspaper. He spoke to older people in Thanet about hoodening. They said it stopped about 50 years before. This was after a woman in Broadstairs was so scared by the horse that she died. He said a wooden head was often used instead of a real horse skull. The hoodening group usually had a "Jockey" who sat on the carrier's back. People would try to knock him off, which sometimes led to fights. The group also had two singers, two helpers, and a man dressed as an "old woman" with a broom. When they knocked on doors, the old woman would sweep people's feet and chase girls until they were paid. Saunders thought the custom was only on the Isle of Thanet. But other letters in 1891 said it was still happening in Deal and Walmer.

Percy Maylam's Research

Percy Maylam was a solicitor and amateur historian. In the 1880s, he started researching hoodening. He looked for mentions of it in books and newspapers. He also interviewed people involved in three active traditions: at St Nicholas-at-Wade, Walmer, and Deal. He wanted to record the custom before it was lost.

Maylam published his research in 1909 as The Hooden Horse. It was praised by other folklorists. Maylam found that only one hooden horse was still actively used in Thanet. This was at Hale Farm in St. Nicholas-at-Wade. It was brought out every Christmas to visit Sarre, Birchington, and St. Nicholas-at-Wade.

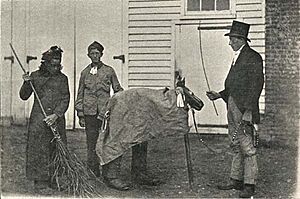

On Christmas Eve 1906, Maylam saw another hooden horse in Walmer. It came into a hotel tearoom with two musicians. The horse was led by a man named Robert Laming. They were wearing normal clothes, but said they used to wear special smocks. They didn't have a Mollie. The hotel owner's daughter put money in the horse's mouth. Then the group moved on to other shops. Maylam later arranged for photos of the Walmer horse and its team.

Maylam also interviewed people involved in the Deal hoodening tradition in 1909. One older man, Robert Skardon, said his father used to lead the group. They had a man dressed as a woman, called a "Daisy," but this had stopped. Skardon had given up the tradition. But the hooden horse was now owned by Elbridge Bowles, who continued the tradition after Christmas each year. They visited Deal and nearby villages. Maylam also learned about a fourth hooden horse owned by farm workers near Sandwich.

Maylam believed the custom would naturally die out. He hoped the hooden horses could be kept in museums. And brought out for special public events to keep them part of Kentish culture. Maylam's book was republished in 2009 as The Kent Hooden Horse. It is still seen as a very important study of the custom.

Hoodening Today

After Maylam's book, hoodening seemed to disappear. Some say the First World War ended the tradition.

Modern Revival

The first time the custom was brought back after the war was at the 1936 Kent District Folk-Dance Festival. A new horse was made for this festival, based on an old one from Sarre. The hobby horse wasn't originally part of Morris dancing. But it became a symbol for some Morris dance groups after the Second World War. Maylam's book greatly influenced this revival.

The Aylesford horse was adopted by the Ravensbourne Morris Men in 1947. This was the first time the custom was known in West Kent. In 1945, a horse was brought out in Acol to celebrate the end of World War II. This was a link between the old tradition and the new revival.

Barnett Field, a folklorist, built a hooden horse for his group, the East Kent Morris Men, in 1953. It was based on the Deal horse from Maylam's book. This horse was shown at the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in June 1953. It was then used by both the East Kent Morris Men and the Handbell Ringers. They took it to perform in Europe, creating "handbell hoodening." The Handbell Ringers also used the horse to collect money for charity at Christmas.

From 1954, the horse was also part of a Whitsun celebration. It was paraded from Charing to Wye. A special church service was held where the Morris Men danced with the horse. In 1956, a pub in Wickhambreaux was renamed The Hooden Horse. This led to a new custom called "hop hoodening." Different groups would tour villages in East Kent, starting at Canterbury Cathedral and ending with a barn dance.

In 1957, Field met Jack Laming, who had been in a hoodening group as a boy. Laming taught Field more about the tradition. They found an old hooden horse at Walmer's Coldblow Farm. This horse is now on display at the Deal Maritime and Local History Museum. In 1961, Field and his wife started the Folkestone International Folklore Festival.

Since World War II, the hooden horse has also been revived in Whitstable. It is often brought out for the Jack in the Green festival in May. A group called the Ancient Order of Hoodeners owns it. Since 1981, the Tonbridge Mummers and Hoodeners have used a horse in a play.

An annual conference for hoodeners was also started. A member of the St. Nicholas-at-Wade hoodeners, Ben Jones, created a website about the tradition. In 2014, a pub in Broadstairs was renamed The Hoodening Horse after the custom. The success of hoodening's revival in Kent might be because people in Kent want to show their unique culture, separate from nearby London.

Images for kids

-

Hoodeners in Deal, Kent in 1909

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |