Hopewell Furnace National Historic Site facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Hopewell Furnace National Historic Site |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Location | Union Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania, USA |

| Nearest city | Reading, Pennsylvania |

| Area | 848 acres (343 ha) |

| Established | August 3, 1938 |

| Visitors | 49,980 (in 2005) |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Hopewell Furnace National Historic Site |

Hopewell Furnace National Historic Site is a special place in southeastern Berks County, near Elverson, Pennsylvania. It shows us what an American 19th-century "iron plantation" was like. An iron plantation was a community built around a furnace that made iron.

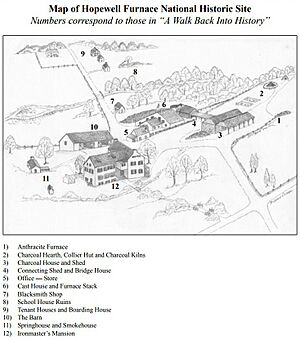

This furnace used charcoal for fuel and a "cold-blast" method to make iron. Many buildings have been restored, like the furnace itself, the big water wheel, and the machinery that helped the furnace work. You can also see the ironmaster's house, a company store, a blacksmith's shop, a barn, and homes where workers lived.

Hopewell Furnace started around 1771. It was founded by an ironmaster named Mark Bird. His father, William Bird, was also a famous ironmaker in Pennsylvania. The furnace was busiest between 1820 and 1840. It even made a lot of iron again during the American Civil War.

But by the mid-1800s, new ways of making iron came along. Furnaces started using anthracite coal instead of charcoal. This made smaller furnaces like Hopewell Furnace old-fashioned. The furnace stopped working in 1883.

In 1938, the government made Hopewell Furnace a National Historic Site. This means it's a very important historical place protected by the National Park Service. It was one of the first cultural sites to join the National Park System.

Today, Hopewell Furnace has 14 restored buildings and covers 848 acres of mostly wooded land. It's part of the Hopewell Big Woods and is surrounded by French Creek State Park and State Game Lands. These areas helped provide the natural resources the furnace needed.

Contents

Mark Bird: The Founder of Hopewell Furnace

Mark Bird took over his family's iron business in 1761 after his father passed away. He owned two forges and a furnace on 3,000 acres of land. Mark Bird quickly made his business much bigger. By 1763, he owned 8,000 acres and added the Hopewell and Jones Good Luck mines.

In 1770, he bought more land in Berks and Chester Counties. He planned to build a new furnace near his father's old forge and the Hopewell mine. By 1771, Hopewell Furnace was up and running. An early stove plate from 1772 even had "Mark Bird-Hopewell Furnace" stamped on it.

Mark Bird's Role in the American Revolution

Mark Bird was also important during the American Revolutionary War. He was a member of the Pennsylvania Committee of Correspondence and the Pennsylvania Provincial Conference. He served as a colonel in the local militia. He was also elected to the Pennsylvania General Assembly and became a judge.

As a Deputy Quartermaster General, his furnace made cannons and cannonballs for the Continental Army and Continental Navy. However, the money he received from Congress was not enough to cover his growing business costs.

Challenges and the End of Bird's Ownership

After the war, the country faced economic problems. Mark Bird had to close his ironworks in Berks County in 1784. He said, "...I was Ruined, by the Warr, it was not Drunkenness, Idleness or want of Industry."

After floods and a fire, Bird had to mortgage his properties in 1786. In 1788, Hopewell Furnace was sold at an auction to James Old and Cadwallader Morris. Mark Bird then moved to North Carolina, a place where people could go to avoid their debts. He passed away there in 1816.

The Buckley Family and Hopewell's Golden Age

By 1789, Hopewell Furnace was the second-largest of 14 furnaces in Pennsylvania. It could make 700 tons of iron each year. But it still wasn't making a profit. In 1794, James Wilson bought the furnace, but he also had to sell it in 1796 and left to avoid his own debts.

Buckley Family Takes Over

In 1800, Daniel Buckley and his brothers-in-law, Matthew and Thomas Brooke, bought Hopewell Furnace. They ran it as a family business for the next 83 years. Daniel Buckley's son, Matthew Brooke Buckley, took over after his father died in 1828. Later, his grandson, Edward S. Buckley, managed the furnace.

The family made many improvements. In 1801, they fixed the bellows, which were used to blow air into the furnace. In 1804, they updated the furnace, built a new charcoal house, and improved the water wheel and water channels. They changed the old overshot wheel to a breastshot wheel.

Making New Products

From 1808 to 1816, the furnace had to close due to a national economic downturn and legal issues. But when it reopened, they added a cupola furnace in 1817. This allowed them to melt pig iron again to make cast iron products.

They made many useful items like sash weights, pots, skillets, kettles, flat irons, and stove plates. The 1830s were the most successful years for Hopewell. From 1825 to 1844, stove plates were their most profitable product. In 1839, they made an amazing 5,152 stoves!

Changes and Closure

Clement Brooke was the manager and ironmaster from 1816 to 1848. He added to the ironmaster's house, made the spring house and company store bigger, and built homes for workers and a schoolhouse.

Stove plate production ended in 1844. For the next four decades, the furnace mainly produced pig iron. One of their customers was the Reading Railroad. The furnace finally stopped working on June 15, 1883. The remaining iron was sold off over the next five years.

Bringing Hopewell Furnace Back to Life

In 1935, the United States government bought the Hopewell Furnace property. They paid $100,000 for 4,000 acres of land. In 1938, the Secretary of the Interior officially named it a National Historic Site.

Plans began to restore the area to how it looked during its busiest time, from 1820 to 1840. In 1946, 5,000 acres of the land were given to the state for recreation. The historic site kept 848 acres.

Restoration work started in the 1950s. By 1952, many parts of the furnace, the blacksmith shop, water wheel, blast machinery, barn, worker houses, and cast house were rebuilt and restored. Workers used traditional methods, like wooden dowels and hand hewn beams, to make it look just like it did in the past.

Challenges and Preservation Efforts

Hopewell Furnace is one of the oldest sites in the National Park Service. Because of its age, it needs a lot of ongoing care and repairs. In recent years, the costs for maintenance have been high.

Local groups are working hard to help. They are focused on saving and organizing old documents from when the furnace was active. This helps everyone better understand and share the history of this important place.

Images for kids

See also

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |