How the Other Half Lives facts for kids

How the Other Half Lives: Studies among the Tenements of New York (1890) is a famous book by Jacob Riis. It was one of the first books to use photojournalism, which means telling stories with pictures. The book showed the terrible living conditions in the poor areas of New York City in the 1880s.

Riis's photographs helped people in the upper and middle classes of New York City see the problems in the slums. This book inspired many changes to improve housing for working-class people. Its impact was felt right away and still influences society today.

Contents

Life in 19th Century New York City

New York City in the 1880s

In the 1880s, many wealthy and middle-class people did not know about the dangerous conditions in the slums. These slums were where many poor immigrants lived. After the American Civil War, the United States became a big industrial country. More and more people moved to cities.

Many immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, Asia, and Jewish communities came to the United States. A lot of them settled in New York City. In the 1880s, over 5.2 million immigrants arrived in the U.S. This caused New York City's population to grow by 25%. This made the housing problem, especially with tenements, much worse.

After the Civil War, some people who used to live in the worst slums became rich enough to move out. Others had died in the war. Also, a new elevated train line built in the Bowery in 1889 made some neighborhoods even worse than before.

People knew about the slum problem even before Riis's book came out. Some reformers thought that sharing wealth more fairly would help. Other groups, like the American Red Cross, tried to help locally. But these efforts were not big enough to solve the whole problem.

What Were Tenements?

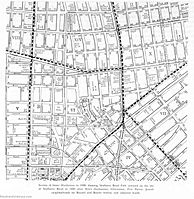

By 1865, New York City had over 15,000 tenement buildings. The city's population was almost 1 million. Tenements were buildings for poor people, designed to fit as many families as possible into a small space. They were usually built on narrow lots, about 25 by 100 feet.

In 1867, a law called the Tenement House Act was passed. It defined a tenement as:

- A building rented to more than three families living separately.

- Or, more than two families on one floor, who cook their own meals.

- These families would share hallways, stairs, yards, or bathrooms.

After this law, a common design for tenements was the "dumbbell" shape. This design was supposed to let in more natural light and fresh air. It also aimed to add more bathrooms and follow new fire safety rules.

However, many landlords did not improve their buildings much. When asked about safety, one building superintendent even said he was happy with hard wood because it "burned slowly." This showed how little some people cared about the safety of tenement residents.

About Jacob Riis

Jacob Riis came to New York City from Denmark in 1870. He wanted to make a name for himself. It was hard for him to find work, and he ended up living in the slums of New York's Lower East Side. After a short trip back to Denmark, he returned to New York and became a police reporter. During this time, Riis became very religious and wanted to help others.

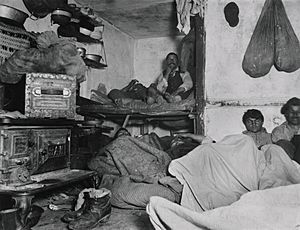

Riis started using photography as a hobby. He soon found it very helpful for his police reports. When he began using magnesium flash powder, he could take pictures in the dark and dirty tenement rooms. This allowed him to show the true conditions.

How the Other Half Lives was not Riis's only book about the slums. He wrote other books like The Children of the Poor and The Battle with the Slums. These books also showed more details about life in these poor areas.

The Book's Story

In January 1888, Riis bought a special camera. He then went on a mission to take pictures of life in the New York City slums. He took his own photos and also used pictures taken by other photographers. On January 28, 1888, Riis gave a presentation called "The Other Half: How It Lives and Dies in New York." He used his images projected onto a screen and described what they showed.

Throughout 1888, Riis continued giving his talks in churches around New York City. Newspapers like New York Sun and New York Evening Post wrote about his lectures.

In February 1889, Riis wrote a magazine article based on his talks for Scribner's Magazine. It was very popular. The full book, How the Other Half Lives: Studies among the Tenements of New York, was published in January 1890.

The book's title comes from a famous French writer named François Rabelais. He wrote, "one half of the world does not know how the other half lives."

How the Other Half Lives described the bad living conditions in New York slums. It also showed the sweatshops inside some tenements, where workers earned only a few cents a day. The book talked about working children, who labored in factories or as newsies (newsboys).

Riis explained that the tenement housing system had failed because of greed and neglect from richer people. He believed that the high crime rates and other problems among the poor were linked to their lack of proper homes. Chapter by chapter, he used his words and photos to show the harsh lives of the poor. His work "spoke directly to people's hearts."

Riis sometimes used words that are not okay today when talking about different groups of people. However, he always believed that the poverty in these communities was caused by the terrible conditions around them, not by the people themselves.

Riis ended How the Other Half Lives with ideas on how to fix the problems. He said that these solutions were possible. He also argued that wealthy people would not only gain financially from helping, but they also had a moral duty to do so.

How the Other Half Lives was different from other charity writings of its time. It used photography to prove the terrible conditions. This helped people understand that the poor were not poor by choice. It showed that the dangerous and unhealthy conditions they lived in were forced upon them by society. Riis convinced people that the slums needed to be fixed, not just ignored.

See also

In Spanish: Cómo vive la otra mitad para niños

In Spanish: Cómo vive la otra mitad para niños