Institución Libre de Enseñanza facts for kids

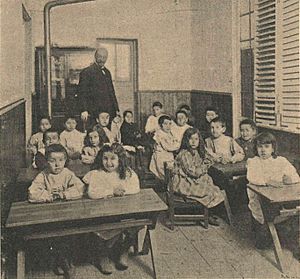

The Institución Libre de Enseñanza (ILE), which means Free Teaching Institution in English, was a special school project in Spain that lasted for over 60 years (from 1876 to 1939). It was inspired by a way of thinking called Krausism, brought to Spain by Julián Sanz del Río. This institution had a huge impact on Spanish thinkers and helped bring new ideas to education in Spain during a time called the Restoration.

The Institución Libre de Enseñanza was started in 1876 because the government, led by Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, was limiting what professors could teach. A group of professors from the Central University of Madrid had been removed from their jobs. They believed in academic freedom, meaning they should be able to teach without being told what to say about religion, politics, or morals. These professors, including Augusto González de Linares, Laureano Calderón, Gumersindo de Azcárate, Teodoro Sainz Rueda, Nicolás Salmerón, Francisco Giner de los Ríos, and Laureano Figuerola (who became the first leader of the ILE), decided to create their own school. They wanted to offer a different kind of education, starting with university-level classes and later expanding to include primary and secondary schools. This new school was private and didn't follow government rules about teaching.

Many important thinkers and artists supported this educational project. Some of them were Joaquín Costa, Leopoldo Alas (Clarín), Ramon Perez de Ayala, José Ortega y Gasset, Gregorio Marañón, Ramón Menéndez Pidal, Antonio Machado, Joaquín Sorolla, Augusto González Linares, Santiago Ramón y Cajal, and Federico Rubio. They all wanted to see education, culture, and society in Spain improve.

Contents

How the ILE Started and Grew

The government at the time, led by Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, wanted Spain to be a very traditional Catholic nation. In 1875, a rule was made that severely limited academic freedom. It said that teaching could not go against the ideas of the conservative Roman Catholicism in Spain. This meant professors couldn't teach anything that challenged traditional religious beliefs.

From 1881 onwards, new teachers who had been trained at the ILE began to teach there. These included Manuel Bartolomé Cossío, who took over from Giner as the head of the Institution, Ricardo Rubio, Pedro Blanco Suárez, Ángel do Rego, José Ontañón Arias, and Pedro Jiménez-Landi. They helped the project grow and ensured its future. The ILE became a very important center for Spanish culture until the Spanish Civil War in 1936. It brought many new and advanced teaching and scientific ideas from other countries into Spain.

Many famous people contributed to The Bulletin of the Institución Libre de Enseñanza, a publication of the ILE. These included Bertrand Russell, Henri Bergson, Charles Darwin, John Dewey, Santiago Ramón y Cajal, Miguel de Unamuno, Montessori, Leo Tolstoy, H. G. Wells, Rabindranath Tagore, Juan Ramón Jiménez, Gabriela Mistral, Benito Perez Galdos, Emilia Pardo Bazán, Azorin, Eugenio d'Ors and Ramón Pérez de Ayala. People closely connected to the ILE were Julián Sanz del Río, Demófilo, and the poets Antonio Machado and Manuel Machado.

The ILE also encouraged studying Spain's past in a new way. This led to the creation of the Center for Historical Studies, led by Ramón Menéndez Pidal, who founded the Spanish school of language studies. The ILE also created places for artists and scientists to connect with new European ideas. Two important examples were the Residencia de Estudiantes, led by Alberto Jiménez Fraud, and the Junta para la Ampliación de Estudios (Board for Advanced Studies and Scientific Research), organized by José Castillejo.

The group of poets known as the Generation of '27 was greatly influenced by the Institución Libre de Enseñanza. However, this period of modernization was stopped by the Spanish Civil War and the Franco dictatorship that followed. Under Franco's rule, all the progressive educational resources of the ILE were taken away. People who supported the ILE were forced to leave the country or faced harsh criticism and punishment if they stayed. Those who left spread their ideas across Europe and Latin America.

In Franco's Spain, the ILE was unfairly blamed for many of the country's problems. For example, in 1940, a group sponsored by a Catholic organization wrote a book attacking the ILE. They even suggested destroying the ILE's children's school in Madrid and covering the ground with salt. This was meant to be a harsh reminder to future generations of what they called "the betrayal" of the ILE.

After Spain became a democracy again in 1978, efforts began to recover the legacy of the ILE. Today, the funds and history of the ILE are managed by the Fundación Francisco Giner de los Ríos, a foundation created for this purpose.

Where the ILE Was Located

The ILE's first planned location was in the Paseo de la Castellana, but the founders decided against it. Instead, they rented an apartment at Calle Esparteros No. 9 (now No. 11). Later, they moved to Infantas No. 42, and then to Paseo del Oblisco No. 8 (which became Paseo del General Martínez Campos No. 14 and No. 16 in 1914).

This new location had a garden and was on the edge of Madrid, which was much better for the ILE's teaching style. In 1908, more buildings were added, including the Giner Pavilion and Soler Hall.

During the Spanish Civil War, the ILE building was badly damaged and looted. Some trees were even cut down by a group of Falangists, leaving only a very old acacia tree and some privet bushes. In 1940, the site was taken over by the Ministry of Education. It was repaired and reopened in 1945 as the Joaquin Sorolla School Group. After 1955, it was used for school food services.

After Spain's return to democracy, the building was briefly used as the Eduardo Marquina National College (1980–1985). Finally, in 1982, it was given back to the Free Institution of Education. Recent updates have given the ILE modern buildings.

How the ILE Influenced Spain

The Institución Libre de Enseñanza played a key role in encouraging the Spanish government to make important changes in laws, education, and society. Because of its influence, the National Pedagogical Museum and the Junta de Ampliación de Estudios were created. The Junta de Ampliación de Estudios, led by José Castillejo, was first set up to send Spanish students to study abroad, no matter their political beliefs. Later, new centers were created under the Junta, like the Center for Historical Studies, the National Institute of Physical-Natural Sciences, and the Residencia de Estudiantes. The Residencia de Estudiantes, directed by Alberto Jiménez Fraud, was a place where many famous writers, artists, and scientists lived and shared ideas. People like Federico García Lorca, Luis Buñuel, Salvador Dalí, Jorge Guillén, and Severo Ochoa lived there. Even Albert Einstein gave a lecture there in 1923.

Between 1907 and 1936, the ILE's ideas for new ways of teaching led to the creation of pioneering projects. These included the Instituto Escuela, school vacation camps, the International Summer University of Santander, and the Misiones Pedagógicas. The Misiones Pedagógicas operated under the Second Republic and aimed to spread education and culture to people in rural areas of Spain.

About a year after Francisco Giner de los Ríos passed away in 1915, his followers created a foundation named after him. This foundation aimed to continue the ILE's work and educational goals. The Foundation published Giner's Complete Works between 1916 and 1936.

Today, there are still schools connected to the Francisco Giner de los Ríos Foundation that continue to use the ILE's educational model, with some changes. One example is the Colegio Estudio, founded in 1940 by Jimena Menéndez Pidal, Angels Gasset, and Carmen Garcia del Diestro. This school educated many Spanish thinkers and politicians. Other similar private schools, like Colegio Base and Colegio Estilo, founded in 1959 by Spanish writer Josefina Aldecoa, also emerged.

A unique example of the ILE's lasting impact is the Colegio Fingoi in Lugo. It was founded in 1950, during the Franco era, by Antonio Fernández López, a businessman who wanted to keep the ILE's ideas alive in Spain.

People Connected to the ILE

Early Members

The first members of the ILE were mostly men who joined Francisco Giner de los Ríos after he returned to the university in 1881. They included Manuel Bartolomé Cossío, Joaquín Costa, Leopoldo Alas (Clarín), Alfredo Calderón, Eduardo Soler, Messia Jacinto Adolfo Posada, Pedro Dorado Montero, Aniceto Sela, and Rafael Altamira.

Second Group of Members

Giner called the younger people who followed the ILE's ideas his "children." This group included Julián Besteiro, Pedro Corominas, José Manuel Pedregal, Martin Navarro Flores, Constancio Bernaldo Quiros, Manuel and Antonio Machado, Domingo Barnés, José Castillejo, Gonzalo Jimenez de la Espada, Luis de Zulueta and Fernando de los Rios.

Third Group of Members

Those born between 1880 and 1890 were known as Giner's "grandchildren." Important students from this time included José Pijoán, Juan Ramón Jiménez, Francisco Ribera Pastor, José Ortega y Gasset, Américo Castro, Gregorio Marañón, Manuel García Morente, Lorenzo Luzuriaga, Paul Azcarate and Alberto Jiménez Fraud.

The Women of the Institución Libre de Enseñanza

Women played a very important role in the ILE, even if their contributions were not always as widely recognized at the time. Over the years, many women involved in ILE projects have been highlighted. Some of these include Amparo Cebrián, Carmen García del Diestro, Laura García Hoppe, Gloria Giner de los Ríos García, María Goyri, Matilde Huici, María de Maeztu, Jimena Menéndez-Pidal, María Moliner, María Luisa Navarro Margati, Alice Pestana, Laura de los Ríos Giner, Concepción Saiz Otero, María Sánchez Arbós, María Zambrano, and Carmen de Zulueta.

One of the most important new ideas from the ILE was its support for women being fully included in society. This meant giving them equal chances to get an education and to have professional careers.

The Asociación para la Enseñanza de la Mujer (Association for the Education of Women) was also created. Its leaders included Manuel Ruíz de Quevedo, Gumersindo de Azcárate, and José Manuel Pedregal. Another ILE member, Aniceto Sela, helped start the Institución para la Enseñanza de la Mujer de Valencia. Several founders of the ILE were involved in projects that helped women in society, such as Juan Facundo Ríaño, Rafael Torres Campos, and Francisco Giner de los Ríos himself, who taught psychology at the Escuela de Institutrices.

See also

In Spanish: Institución Libre de Enseñanza para niños

In Spanish: Institución Libre de Enseñanza para niños

- Escuela Moderna

- Generation of '98

- Noucentisme

- Regenerationism

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |