Jack Cade's Rebellion facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Jack Cade's Rebellion |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

Jack Cade's Rebellion, shown in a mural of the history of the Old Kent Road

|

|||

| Date | 1450 | ||

| Location |

South-east England

|

||

| Resulted in | Government victory | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|

|||

| Lead figures | |||

|

|||

| Casualties | |||

|

|||

Jack Cade's Rebellion was a big uprising in 1450 against the English government. It took place in the south-east of England between April and July. People were unhappy with unfair rules and corrupt officials close to the king. England had also lost battles in France during the Hundred Years' War.

Jack Cade led an army of men from south-eastern England. He marched on London to make the government change. He wanted to remove the "traitors" he blamed for bad leadership. This was one of the biggest uprisings in England during the 1400s.

When the rebels entered London, some of them started taking things. The people of London then turned against the rebels. They fought a bloody battle on London Bridge. To stop the fighting, the king offered pardons to the rebels. He told them to go home. Cade ran away but was caught on 12 July 1450 by Alexander Iden. Cade was badly hurt and died before he could be put on trial in London. This rebellion showed the problems in England at the time. It also set the stage for the Wars of the Roses.

Contents

Who Was Jack Cade?

|

Jack Cade

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1420–1430 Probably Sussex

|

| Died | 12 July 1450 Cade Street, Sussex

|

| Other names |

|

| Known for | Jack Cade's rebellion |

We do not know much about Jack (or John) Cade. He did not leave any personal papers. Rebels often used fake names, so historians have to guess based on rumors. Historians believe he was born in Sussex between 1420 and 1430. They agree he was from the lower classes of society.

During the rebellion, Cade called himself "Captain of Kent." He also used the name "John Mortimer." The name "Mortimer" was a problem for King Henry VI. This was because Henry's main rival for the throne was Richard, Duke of York. Richard had Mortimer family connections through his mother.

The idea that Cade might be working with York made the king act quickly. At the time, the Duke of York was in Ireland. There is no proof that he helped fund or start the uprising. Cade likely used the name "Mortimer" to make his cause seem more important. When the rebels were pardoned on 7 July 1450, Cade got a pardon as "Mortimer." But when it was found out he lied about his name, the pardon was canceled.

Cade's followers called him "John Mend-all" or "John Amend-all." This was because he wanted to fix people's complaints. He also wanted to bring order back to the government. We do not know if Cade chose this nickname himself.

Why Did the Rebellion Start?

Before Jack Cade's Rebellion, England faced many problems. People were growing more unhappy with King Henry VI. Years of war against France had made the country poor. Losing battles in France also made people worried about an invasion. Coastal areas like Kent and Sussex were already being attacked by French soldiers.

The English government did not give enough supplies to its soldiers. So, soldiers often took things from towns on their way to France. The people who lost their goods got no help. The king's order to set up warning fires along the coast made people even more afraid of a French attack. These fears made many English people join together. They wanted the king to fix their problems or step down.

At court, there were disagreements about the war with France. King Henry wanted peace. But his uncle, the Duke of Gloucester, and other nobles wanted to keep fighting. These arguments led to the king's close friend, William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk, being sent away.

Many people also believed the king had bad and dishonest advisors. The Duke of Suffolk was at the center of these problems. When the duke's body was found on the shores of Dover, the people of Kent were scared. Rumors spread that the king would punish Kent for the duke's death. People were tired of the Duke of Suffolk's unfair ways. So, the common people of Kent, led by Jack Cade, marched on London. About 5,000 people joined the uprising.

In the spring of 1450, Cade helped create a list of complaints. It was called "The Complaint of the Poor Commons of Kent." This list showed the problems of the common people. It also included concerns from some members of parliament and nobles. The document had fifteen complaints and five demands for the king.

One main point was that Cade's followers were wrongly blamed for the Duke of Suffolk's death. The rebels also wanted investigations into dishonest actions in government. They asked for corrupt high officials to be removed. Cade's list said King Henry was unfair for not punishing his dishonest officials. These officials were accused of cheating in elections and taking money unfairly. They were also accused of using their power to hurt others.

Besides the Duke of Suffolk, the rebels specifically named Lord Saye and officials Crowmer, Isley, and St Leger. Lord Saye and his son-in-law Crowmer were close to the king. They held important jobs in Kent. Both had been High Sheriff of Kent and members of the king's council. In 1449, Saye became the Lord High Treasurer. Isley and St Leger also served as Sheriffs and MPs in Kent. When the king did not fix their problems, the rebels marched on London.

The Uprising Begins

In May 1450, the rebels started to gather in an organized way. They began to move towards London. Cade sent messengers to nearby areas to ask for more help and men. By early June, over 5,000 men had gathered at Blackheath. This was about 6 miles (9.7 km) south-east of the City of London. Most of them were farmers, but there were also shopkeepers, craftsmen, and some landowners. Some soldiers and sailors returning from the French wars also joined.

The king wanted to stop the rebellion quickly. He sent a small group of his royal soldiers to end it. Sir Humphrey Stafford and his cousin William Stafford led the royal forces.

The royal forces did not realize how strong the rebels were. They were led into a trap at Sevenoaks. In a fight on 18 June 1450, both Stafford cousins were killed. Cade took Sir Humphrey's expensive clothes and armor for himself.

On 28 June, William Ayscough, the unpopular Bishop of Salisbury, was killed by an angry crowd in Wiltshire. William Ayscough was the king's personal advisor. His position made him one of the most powerful men in the country. The king was afraid he might be next. He was also shocked by the rebels' fighting skill. So, the king went to Warwickshire for safety.

Feeling stronger after their victory, the rebels moved to Southwark. This was at the southern end of London Bridge. Cade set up his base at The White Hart inn. On 3 July 1450, he crossed the bridge and entered the city with his followers. To make sure he could move freely, Cade cut the ropes on the bridge. This stopped it from being raised against him.

When he entered London, Cade stopped at the London Stone. He hit the stone with his sword and declared himself Lord Mayor. This was a traditional way to claim power. By hitting the stone, Cade was symbolically taking back the country for the Mortimers. He claimed to be related to them.

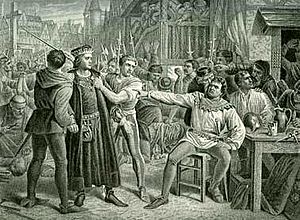

Inside the city, Cade and his men started trials. They looked for and punished those accused of corruption. At Guildhall on 4 July, James Fiennes, 1st Baron Saye and Sele, the Lord High Treasurer, was put on a quick trial. He was found guilty and taken to Cheapside. There, he was executed.

Fiennes' son-in-law, William Crowmer, was also executed by the rebels. The heads of the two men were put on poles. They were paraded through the streets of London. Their heads were then put on London Bridge.

Cade had promised his followers would behave well. But as the rebels moved through the city, many, including Cade, started to take things. They also acted disorderly.

Slowly, Cade's inability to control his men made the people of London turn against them. The citizens had first felt sympathy for the rebels. On 7 July, Cade's army went back over the bridge to Southwark for the night. London officials then closed the bridge to stop Cade from re-entering the city.

The next day, 8 July, a battle started on London Bridge. It was between Cade's army and the citizens and officials of London. The fight lasted until the next morning. The rebels had to retreat, and many were hurt or killed. One writer said that at least 40 Londoners and 200 rebels died in the battle.

Cade's Capture

After the battle on London Bridge, Archbishop John Kemp (the Lord Chancellor) convinced Cade to send his followers home. He did this by offering official pardons and promising to meet the rebels' demands. However, King Henry VI soon canceled all the pardons he had given.

The king issued a document called "Writ and Proclamation by the King for the Taking of Cade." In it, the king said the pardons were not approved by Parliament. He accused Cade of tricking people into joining his rebellion. The king also said no one should help Cade. A reward of 1000 marks was offered to anyone who could capture Jack Cade, dead or alive.

Cade fled towards Lewes. But on 12 July, he was caught by Alexander Iden in a garden where he was hiding. Iden would later marry the widow of William Crowmer, who the rebels had executed. In the fight, Cade was badly wounded. He died before he could be taken to London for trial. To warn others, Cade's body was put on a mock trial and then executed at Newgate. His body was dragged through London. Then, his body was divided. His body parts were sent to different towns in Kent. These towns were believed to have strongly supported the rebellion.

What Happened Next?

To stop more uprisings, Humphrey Stafford, 1st Duke of Buckingham got permission from the king. He was to find the rest of Cade's followers and bring them to trial. The search happened in areas where the rebellion had strong support. These included Blackheath, Canterbury, and the coastal areas of Faversham and the Isle of Sheppey. The investigations were very thorough. In Canterbury, eight followers were quickly found and executed.

Even though Jack Cade's Rebellion ended after his death, the feeling of rebellion did not go away. Inspired by Cade, many other areas in England revolted. In Sussex, the yeomen brothers John and William Merfold started their own rebellion. Unlike Cade's revolt, the men of Sussex were more extreme in their demands. This anger might have grown because the king had canceled the pardons. A document after the Sussex rebellion said the rebels wanted to kill the king and all his lords. They wanted to replace them with twelve of their own men. The rebellions in Sussex did not get as many followers as Cade's.

These smaller rebellions did not cause many deaths or immediate changes. But they were important steps leading to the Wars of the Roses. These big battles for the English crown would end the Lancaster family's rule. They would also bring the York family to power. The weakness of the Lancaster family and the English government had been shown.

Also, Cade's list of demands asked the king to welcome the Duke of York as his advisor. This clearly told the king that people wanted the duke to return from exile. When Richard, Duke of York, finally came back to England in September 1450, some of his demands were based on Cade's manifesto.

Images for kids

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |