London Stone facts for kids

The London Stone is a very old and famous landmark in the City of London. It is a piece of stone found at 111 Cannon Street. The stone is made of oolitic limestone and measures about 53 by 43 by 30 centimeters (21 by 17 by 12 inches). It is what's left of a much bigger stone that stood in the same area for many centuries.

The name "London Stone" was first written down around the year 1100. Nobody knows for sure when the Stone was first put there or why. Some people think it might be from the Roman times. People have been curious about it since the Middle Ages. However, modern ideas that it was a special religious object or has magic powers are not true.

Contents

What the London Stone Looks Like

The London Stone you see today is only the top part of what was once a much larger object. It is a block of oolitic limestone. This type of stone is made from tiny round grains. The stone is about 53 cm wide, 43 cm high, and 30 cm deep.

Experts in the 1960s thought the stone was Clipsham Limestone. This is a good quality stone from Rutland that was used for building in Roman and medieval times. More recently, some think it might be Bath stone. This stone was often used for monuments and sculptures in early Roman London.

The Stone is now on the north side of Cannon Street. It is across from Cannon Street station. You can see it in a special opening in the wall of the building at 111 Cannon Street. It is protected by a Portland stone frame.

History of the London Stone

Nobody knows exactly when the London Stone was put in place or what its first job was. There have been many guesses over the years.

The Stone was first on the south side of a street called Candlewick Street. This street later became modern Cannon Street. It was across from the west end of St Swithin's Church. Old maps from the 1550s and 1560s show it in this spot.

A London historian named John Stow wrote about it in 1598. He called it "a great stone called London stone." He said it was "pitched upright" and "fixed in the ground verie deep." A visitor from France in 1578 said the Stone was about 90 cm (three feet) tall above ground. It was also 60 cm (two feet) wide and 30 cm (one foot) thick. So, even though it was a famous landmark, the part of the Stone above ground was not huge.

The Stone in the Middle Ages

The earliest mention of the Stone is thought to be around the year 1100. A record from Canterbury Cathedral talks about land "neare unto London stone." This record was about a property given to the cathedral by a man named "Eadwaker at London Stone." This means people lived near the Stone and used its name to describe where they were.

Many people in medieval London took the byname "at London Stone." This was because they lived close to it. One famous person was "Ailwin of London Stone." He was the father of Henry Fitz-Ailwin. Henry was the first Mayor of the City of London. He became mayor between 1189 and 1193 and led the city until he died in 1212.

The London Stone was a very well-known landmark. In 1450, a man named Jack Cade led a rebellion. He was fighting against the government of King Henry VI. When Cade and his men entered London, he struck his sword on London Stone. He then said he was "Lord of this city." People at the time did not say why he did this. There is no sign that it was a traditional ceremony.

From the 16th to 17th Centuries

By the time of Queen Elizabeth I, the London Stone was more than just a landmark. It was a place tourists wanted to see. Visitors might have heard different stories about it. Some said it was there before London even existed. Others claimed King Lud, a legendary builder of London, put it there. People also thought it marked the center of the city. It was also used for putting up notices and advertisements. In 1608, a poem listed it as one of London's "sights."

During the 17th century, the Stone was still used as a way to describe a location. For example, a book about Queen Elizabeth I was sold at a shop "neere London stone." Many other books from this time also mentioned London Stone in their publishing details.

In 1671, a group called the Worshipful Company of Spectacle Makers used the Stone. They broke many bad quality spectacles on it. They said the glasses and frames were "not fitt to be put on sale." So, they were "broken in all pieces" on the "remayning parte of London Stone." This might mean the Stone was already smaller. Perhaps it was damaged in the Great Fire of London five years earlier. The fire had destroyed St Swithin's church and nearby buildings. Later, a small stone cover was put over the Stone to protect it.

From the 18th Century to Early 20th Century

In 1598, John Stow noted that if carts hit the Stone, their wheels would break, but the Stone would stay strong. By 1742, it was getting in the way of traffic. The remaining part of the Stone was moved from the south side of the street to the north side. It was first placed next to the door of St Swithin's Church. This church had been rebuilt by Christopher Wren after the Great Fire.

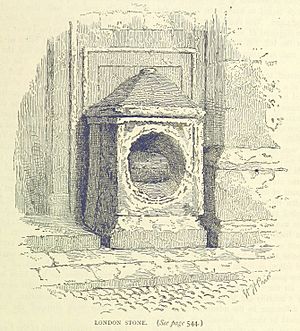

It was moved again in 1798. Then, in the 1820s, it was placed in a special space in the middle of the church wall. It had a strong stone frame and a round opening to see the Stone. In 1869, a group called the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society added a protective iron grille. They also put up a sign in Latin and English above it.

In the 1800s and 1900s, London Stone was often mentioned in history books and guidebooks. Tourists would visit it. The American writer Nathaniel Hawthorne saw it in the 1850s. He wrote about the marks on top, which people said were made by Jack Cade's sword.

In 1937, Arthur Mee, who started The Children's Newspaper, described it as "a fragment of its old self." He said some believed it was "a stone set up in Stone Age days." An American archaeologist, George Byron Gordon, wrote about it in 1924. He said London Stone was "the very oldest object in London streets." He even claimed medieval kings would strike it with their swords after being crowned. These stories, while fun, are not true.

From 1940 to Today

In 1940, St Swithin's church was badly damaged by bombs during the Blitz. But the outer walls stayed standing for many years. London Stone was still in its place in the south wall. In 1962, the church ruins were taken down. A new office building, 111 Cannon Street, was built there. London Stone was placed in a new Portland stone alcove in this building. It had glass and an iron grille to protect it. Inside the building, it was behind a glass case. The Stone and its casing became a special listed structure in 1972.

In the early 2000s, the office building was planned to be rebuilt. In 2011, there was a plan to move the Stone to a new spot. But groups like the Victorian Society and English Heritage objected. The plan was stopped.

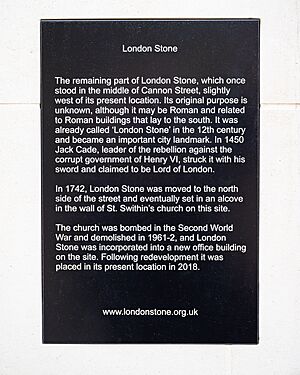

Until 2016, a WHSmith shop was on the ground floor of the building. The London Stone was hidden behind a magazine rack inside the shop. It was not easy to see. In March 2016, permission was given to knock down the building and build a new one. The Stone was moved to the Museum of London for a while. It came back to Cannon Street in October 2018. The new building now shows London Stone publicly. It is on a stand, inside a Portland stone case, and behind glass. A sign next to the Stone tells its story:

London Stone This is the remaining part of London Stone. It once stood in the middle of Cannon Street, a little west of here. We don't know its first purpose, but it might be Roman. It was called 'London Stone' by the 1100s and became a major city landmark. In 1450, Jack Cade, who led a rebellion, struck it with his sword and said he was Lord of London.

In 1742, London Stone was moved to the north side of the street. It was later placed in a special spot in the wall of St. Swithin's church, which was on this site.

The church was bombed in World War II and taken down in 1961–62. London Stone was then put into a new office building here. After the building was redeveloped, it was placed in its current spot in 2018.

The London Stone in Stories

Because the London Stone was so well-known, it often appeared in London stories and literature.

Old Stories and Plays

In an old poem from the early 1400s called "London Lickpenny," a lost person walks past London Stone. The poem says:

Then went I forth by London Stone

Thrwgheout all Canywike Strete...

Around 1522, a funny poem was published. It was about a wedding between London Stone and a water fountain called the "Bosse of Byllyngesgate." The poem joked about them dancing. It suggested that both the Stone and the fountain were known for being strong and reliable.

The story of Jack Cade and the Stone was made into a play by William Shakespeare. It's in his play Henry VI, Part 2. In the play, Cade hits London Stone with a staff, not a sword. Then he sits on the Stone like a king and gives orders.

In 1598, London Stone was in another play called Englishmen for My Money. In this comedy, three foreigners get lost in London at night and bump into the Stone.

Later, the London Stone was important in the writings of William Blake. In his long poem Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion, he wrote that London Stone was a Druidic altar where sacrifices happened. In other works, he saw it as the center of his magical city of London, a place for justice.

Modern Books and Comics

In recent years, the Stone has appeared more often in fantasy novels. In Peter Ackroyd's novel The House of Doctor Dee (1993), a character believes London Stone is the last part of a great, lost city.

London Stone is shown as an evil object in Charlie Fletcher's children's books, the Stoneheart trilogy (2006–2008). It also appears in The Midnight Mayor (2010) by Kate Griffin. In China Miéville's Kraken (2010), the Stone is the heart of London. The shop that housed it hides the headquarters of "Londonmancers," who know about magic in the city.

The third book in The Nowhere Chronicles by Sarah Pinborough is called The London Stone (2012). It's about the Stone being stolen. In Marie Brennan's Onyx Court series (2008–2011), the Stone is part of a magic link between humans and the fairy world under London.

The Stone is in several parts of Edward Rutherfurd's novel, London (1997). It is shown as a marker for Roman roads. It also helps connect different time periods in the story.

The Stone is a main part of a DC Comics Vertigo story called The Knowledge (2008). It features John Constantine's friend, Chas Chandler. The Stone also appears in the Dark Fae FBI series (2017) by C. N. Crawford and Alex Rivers. In these books, it is a place for old sacrifices and channels memories and power.

The Stone is also mentioned in Nicci French's crime novel Tuesday's Gone (2013).

See also

In Spanish: London Stone para niños

In Spanish: London Stone para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |