Jacob Gens facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jacob Gens

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | 1 April 1903 Ilgviečiai, Russian Empire

|

| Died | 14 September 1943 (aged 40) Vilnius, German-occupied Lithuania

|

| Cause of death | Execution |

| Nationality | Lithuanian |

| Known for | Head of the Jewish police of the Vilnius Ghetto Head of the Vilnius Ghetto |

Jacob Gens (born April 1, 1903 – died September 14, 1943) was a very important leader in the Vilnius Ghetto during World War II. The Vilnius Ghetto was a small, crowded area in the city of Vilnius (now in Lithuania) where Jewish people were forced to live by the Germans.

Gens came from a family of merchants. After Lithuania became independent, he joined the Lithuanian Army and became a captain. He also studied law and economics at college. He worked as a teacher, accountant, and administrator. He was married to a woman who was not Jewish.

When Germany invaded Lithuania, Gens first led the Jewish hospital in Vilnius. In September 1941, when the ghetto was created, he became the chief of the ghetto's police force. In July 1942, the Germans made him the head of the entire Jewish government inside the ghetto. Gens tried to make life better for the people in the ghetto. He believed that by working for the Germans, he could save some Jewish lives.

However, Gens and his police also helped the Germans gather Jewish people for deportation and execution. This happened in late 1941 and when smaller ghettos were closed down in 1942 and 1943. His actions, especially his difficult choices to save some people by giving up others, are still debated today.

The Gestapo (German secret police) executed Gens on September 14, 1943. This happened just before the Vilnius Ghetto was completely destroyed. Most of its residents were sent to forced labor camps or death camps. Gens' wife and daughter managed to escape the Gestapo and survived the war.

Contents

Early Life and Career

Jacob Gens was born on April 1, 1903, in a place called Ilgviečiai, which is now in Lithuania. His father was a merchant, and Jacob was the oldest of four sons. He went to school and learned many languages, including Lithuanian, Russian, German, and Yiddish.

In 1919, Gens joined the new Lithuanian Army. He became an officer and was known for his leadership skills and good mood. He fought in the Polish–Lithuanian War.

After leaving the regular army in 1924, Gens taught physical education and Lithuanian at a Jewish school. He married Elvyra Budreikaitė, who was not Jewish, and they had a daughter named Ada in 1926. Gens continued his studies at Kaunas University and worked for the Ministry of Justice. He earned a degree in law and economics in 1935. Later, he returned to the army and was promoted to captain. He also worked for a company called Shell Oil and a Lithuanian co-operative.

Gens was a Zionist, which means he supported the idea of creating a Jewish homeland in what was then called Palestine.

Leading the Jewish Hospital

When the Soviet Union took over Lithuania in 1940, Gens lost his job. He moved to Vilnius and found a hidden job at the Jewish hospital. He managed to avoid being sent to Soviet labor camps.

On June 24, 1941, the German Army entered Vilnius. Gens was then put in charge of the Jewish hospital. The Germans ordered the creation of a Judenrat, or Jewish Council, to manage the Jewish community. In September 1941, the Germans killed most of the first Judenrat members.

When the Vilnius Ghetto was formed, the Jewish hospital was included inside the larger ghetto. This was unusual, as most ghettos did not have their hospitals inside.

Chief of the Ghetto Police

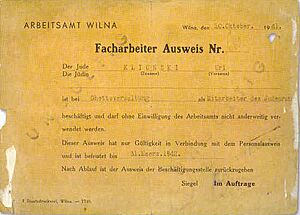

In September 1941, Jacob Gens was made the commander of the Jewish Ghetto Police in the Vilnius Ghetto. His main jobs were to follow German and Judenrat orders and to keep law and order inside the ghetto. A very important task was to find any anti-German activities.

The police force started with about 200 men. Gens chose Salk Dessler as his second-in-command. Many police officers, including Gens, were part of a Jewish political group called Revisionist Zionists. This sometimes caused disagreements with other Jewish political groups in the ghetto.

Difficult Choices in 1941

In late 1941, the Germans began "Aktions" in the ghetto. These were selections of people who would be deported and killed at a nearby place called Ponary. Gens was worried that these actions would lead to a huge massacre of everyone. He convinced the Gestapo to let the Jewish police gather the people to be deported.

Gens and his police had to decide who would be sent away. This was a terrible and controversial task. He believed it was necessary to sacrifice some people to save others. He tried to get more work permits from the Germans, but they refused.

During one "Aktion" in November, people's work permits were checked. These permits allowed a person to protect their spouse and two children under 16. Gens tried to save extra children. For example, he once moved a third child from one family to another family that only had one child, right under the noses of German officials.

All the people taken from the ghetto were killed at Ponary. By December 1941, only about 12,500 to 17,200 residents were left in the ghetto. Before the German occupation, about 60,000 Jews lived in Vilnius.

Gens and the Judenrat knew about the killings at Ponary by the end of September 1941, when some survivors returned. Gens urged them to keep quiet to avoid panic. By late December 1941, most people in the ghetto knew about the massacres.

Working with the Judenrat

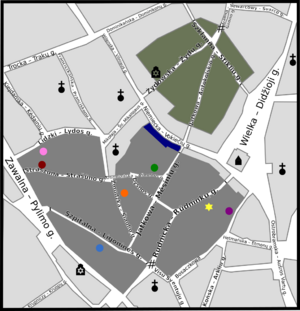

After the "Aktions" of 1941, there were no more large-scale deportations from the Vilnius Ghetto for a while. This calm period lasted through 1942 and early 1943. During this time, Gens' police department managed the ghetto's three police areas and its prison.

Gens became more powerful than the head of the Judenrat, Anatol Friend. The Germans supported Gens, making it clear that he was not under the Judenrat's control. Gens was popular with the ghetto residents, partly because he chose to live in the ghetto even though he might have been able to escape.

The Jewish police controlled who could enter and leave the ghetto. Gens' policy was to allow smuggling of food and other needed items when no Germans were watching. But if Germans were present, the police would search thoroughly and sometimes beat smugglers. Gens believed that if the Germans thought the Jewish police weren't strict enough, they would replace them with German guards, which would stop all smuggling. He also said that even when Germans were present, any confiscated items were brought into the ghetto for the residents, which wouldn't happen with German guards.

Head of the Vilnius Ghetto

On July 10, 1942, the Germans dissolved the Judenrat because they thought it was not effective. Gens was then appointed as the overall head of the ghetto. He kept his role as police chief and was called "chief of the ghetto and police in Vilnius." He asked the former Judenrat members to stay on as heads of different departments, and they agreed.

Gens' Ideas and Actions

Some ghetto residents jokingly called Gens "King Jacob the First." Historians describe him as a strong leader who made important decisions for the ghetto's survival. Gens believed that working for the Germans was the only way for some people to survive. He hoped to keep some of the ghetto residents alive until the Nazi occupation ended. He was very strict and believed he alone could save a part of the ghetto's population. This belief makes him a controversial figure even today.

Closing Smaller Ghettos

In late 1942, the Germans began to close down smaller ghettos in the Vilnius area, and Gens helped them. These included ghettos in Oszmiana, Švenčionys, Soly, and Michaliszki. During one of these actions on October 25, Gens gave up 400 elderly people from Oszmiana to save the remaining 600 Jewish residents. He even bribed a Nazi officer to accept the lower number. The Jewish police from Vilnius, along with some Lithuanians, were forced to kill the 400 Jews. Some people in the Vilnius ghetto were very upset by Gens' involvement, but others felt he made the right choice to save some lives.

By April 1943, most of these small ghettos were gone. Their residents were either moved to labor camps, shot, or sent to the Vilnius Ghetto. On April 4–5, the last residents were put on trains under the supervision of the Vilnius Jewish police. Gens joined his policemen when the train passed through Vilnius and was arrested with them when the train arrived at Ponary. Gens and the policemen were released, but the other Jews on the train were killed. It seems the Germans tricked Gens about where the trains were going. Gens defended his actions by saying that the Jewish police's involvement saved at least some ghetto residents who would otherwise have been killed by the Germans.

Working with Jewish Resistance

Gens had a difficult relationship with the Jewish resistance groups. He allowed some resistance members to escape the ghetto. However, he was against their plans for armed resistance because he feared it would put the entire ghetto in danger. Gens did promise to help the resistance groups and may have said he would join a revolt if the time was right. He gave money from the Judenrat funds to the Fareynikte Partizaner Organizatsye (FPO), a resistance group. He also provided a pistol to another resistance group called the "Struggle Group."

In July 1943, a German officer demanded that Gens hand over Yitzhak Wittenberg, a leader of the FPO. Wittenberg was arrested but freed by FPO members. Gens then spread the word that if Wittenberg did not surrender, the Germans would destroy the ghetto. The ghetto residents supported Gens in this difficult situation. On July 16, Wittenberg turned himself in and died soon after.

Welfare and Cultural Activities

While Gens was in charge, he made sure the ghetto had good sanitation and health services. Even though the ghetto was very crowded and often dirty, there were no major epidemics, and fewer people died from disease compared to other ghettos. Children's homes were set up in March 1942 for orphans or children whose parents couldn't care for them.

In May 1942, Gens got German permission for ghetto residents to sell their belongings that they had left with non-Jewish people outside the ghetto. This allowed residents to get some value for their property. In October 1942, the Jewish police were allowed to bring Jewish property back into the ghetto. Gens also started a program to collect, repair, and give out winter clothing to the poor. This helped many people survive the cold winter of 1942–1943.

Gens also started a theater in the ghetto, where people could enjoy plays and poetry readings. He supported the ghetto library and even ordered all residents to give their privately owned books (except textbooks and prayer books) to the library. He also tried to set up a publishing house. Gens believed these cultural activities helped people feel free from the harsh reality of the ghetto, saying, "Our body is here in the ghetto, but they have not broken our spirit."

Family and Privileges

Gens' wife and daughter lived near the ghetto. His wife used her maiden name to protect herself and their daughter. Gens did not deny rumors that they were divorced, thinking it would help keep his family safe. In a letter to his wife, Gens wrote, "My heart is broken. But I shall always do what is necessary for the sake of the Jews in the ghetto."

Gens' mother and a brother, Solomon, were also in the Vilnius Ghetto. Another brother, Ephraim, was the head of the ghetto police in the Šiauliai Ghetto and was the only Gens brother to survive the Holocaust.

The Germans gave Gens some special privileges. He did not have to wear the yellow badge (Star of David) on his clothes like other Jews. Instead, he wore a white and blue armband. He could enter and leave the ghetto freely, and his daughter did not have to live in the ghetto. Gens and the Jewish police were also allowed to carry pistols.

Death and Legacy

On September 13, 1943, the Germans ordered Gens to report to the Gestapo headquarters the next day. He was told to run away, but he chose to go, saying that if he fled, "thousands of Jews will pay for it with their lives." Jacob Gens was executed by the head of the Vilnius Gestapo on September 14, 1943. The Gestapo claimed he was killed for giving money to the FPO resistance group.

The Vilnius Ghetto was completely destroyed between September 22 and 24, 1943. Thousands of residents were sent to labor camps, while 5,000 women and children were sent to Majdanek, where they were killed. Hundreds of elderly and sick people were shot at Ponary. A few Jewish people who remained in Vilnius were shot just before the Soviet Army arrived. Some FPO members escaped to the nearby forests.

Gens' wife and daughter were informed of his death by a Jewish policeman and managed to hide until Soviet troops arrived. They later moved to Australia and then to the United States.

Historians have debated the role of Jewish leaders like Gens in the ghettos. Some early historians criticized them for helping the Germans. However, more recent historians understand that these leaders faced incredibly difficult choices with almost no power to change the Germans' demands.

Jacob Gens is considered "one of the most controversial Jewish ghetto leaders." Some say his actions were harmful, but others believe he always tried to do what was best for his people. Historian Yitzhak Arad said that Gens' policy was "the only one that afforded hope and some prospect of survival." Another historian, Vadim Altskan, noted that Jewish leaders had no experience dealing with such terrible situations.

Gens is a main character in Joshua Sobol's plays Ghetto and Adam. These plays show him as a complex person forced to make impossible choices between two bad options.