James Burnett, Lord Monboddo facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Lord Monboddo

|

|

|---|---|

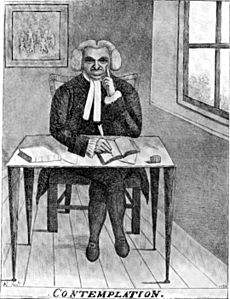

Engraving of Lord Monboddo by C. Sherwin, 1787 (after John Brown)

|

|

| Born | bapt. 25 October 1714 Monboddo House, Kincardineshire, Scotland

|

| Died | 26 May 1799 (aged 84) Edinburgh, Scotland

|

| Education | Marischal College, University of Aberdeen University of Edinburgh |

| Occupation | Philosopher, linguist, judge |

James Burnett, Lord Monboddo (born 1714, died 1799) was a Scottish judge and a very smart thinker. He was interested in how languages change over time and how humans might have developed.

He is best known today for his early ideas about how languages and even humans themselves have changed and grown over many years. In 1767, he became a judge in Scotland's highest court, the Court of Session.

As a judge, Burnett took the special title "Lord Monboddo," named after his family's home, Monboddo House. He was one of many scholars at the time who started thinking about how living things might change over time. Some people even say he had ideas similar to natural selection, which was later written about by Erasmus Darwin. Erasmus Darwin's grandson, Charles Darwin, later developed these ideas into the famous scientific theory of evolution.

Contents

Early Life and Family

James Burnett was born in 1714 at Monboddo House in Scotland. He went to school in his local area, then studied at Marischal College in Aberdeen. After that, he studied law at the University of Groningen for three years.

In 1736, he returned to Scotland and became a lawyer in Edinburgh. He married Elizabethe Farquharson, and they had two daughters and a son. His younger daughter, Elizabeth Burnett, was well-known in Edinburgh for her beauty. Sadly, she died young, at age 24.

James Burnett's friend, the famous Scottish poet Robert Burns, liked Elizabeth very much. He even wrote a poem about her, praising her beauty.

Early in his law career, Burnett worked on a very important case called the Douglas "cause." It was about who should inherit a large family fortune. The case was very complicated, like a mystery novel, and involved events in Scotland, France, and England. Burnett worked for the young heir and won the case after many years of legal battles.

A Judge and Thinker

From 1754 to 1767, Lord Monboddo helped run the Canongate Theatre. He really enjoyed this, even though some other judges thought it wasn't serious enough for a judge. He even met David Hume there, who was a famous thinker and acted in one of the plays.

After becoming a high court judge, Monboddo started holding "learned suppers" at his home in Edinburgh. At these dinners, he would talk about his ideas with other smart people. He would ride his horse to London every year and visit other thinkers there. Even the King enjoyed his interesting discussions!

Lord Monboddo died at his home in Edinburgh on May 26, 1799. He is buried in Greyfriars Kirkyard in Edinburgh, along with his daughter Elizabeth.

Ideas on Language

In his large book series, The Origin and Progress of Language (published from 1774 to 1792), Burnett looked at how languages are built. He believed that humans developed language skills as their surroundings and ways of living changed.

He was one of the first to notice that some languages use very long words for simple ideas. He thought that in early languages, people needed to be very clear. So, they added extra sounds to words to make sure they were understood. He believed this happened when clear talking was important for staying safe.

Monboddo studied the languages of people from different parts of the world, like the Island Caribs, Eskimo, Huron, and Tahitian peoples. He saw that these languages often had many syllables in their words, even though some earlier thinkers had thought they were just simple grunts.

He also had the idea that these languages often had many vowel sounds, while languages like German and English had fewer. He thought this was partly because Northern European languages had more words, so they didn't need to make words as long to be clear.

Monboddo also thought that the ancient Greek language was the most perfect language. He believed this because of its complex structure and sounds, which allowed it to express many different feelings and ideas. He was also the first to suggest the idea that all humans originally came from one place on Earth. He came to this idea by thinking about how languages changed over time. This shows how he was thinking about the evolution of humans.

Thinking About Evolution

Some scholars see Monboddo as an early thinker in the theory of evolution. He explored how language and society began and had ideas similar to Darwin's later theory.

One of his successors, Charles Neaves, felt that Monboddo didn't get enough credit for his ideas on evolution. Erasmus Darwin (Charles Darwin's grandfather) mentioned Monboddo's work in his own books.

Monboddo also debated with another scientist named Buffon about how humans are related to other primates. Buffon thought humans were completely separate from apes, but Monboddo disagreed. He argued that apes must be related to humans, sometimes calling them the "brother of man."

Monboddo once said that humans might have been born with tails that were removed at birth. This made some people laugh at him, and he later took back this idea. But even with this unusual idea, many people see him as someone who thought about evolution before it became a widely accepted theory.

He seemed to argue that animal species changed and adapted to survive. His observations about how primates might have developed into humans showed he had some idea of evolution. Monboddo also studied children who grew up away from people (called feral children). He was one of the few thinkers of his time who saw them as human, not monsters, and believed they could learn to reason.

Monboddo also thought about how humans learned to use tools first, then developed social groups, and finally created language. This was a very new idea for his time, as many people believed God had created humans and given them language instantly. However, Monboddo was a very religious person. He believed that the stories of creation were like allegories (symbolic stories) and didn't doubt that God created the universe.

As a farmer and horse breeder, Monboddo understood how important selective breeding was. He even applied this idea to humans, suggesting that people could improve future generations by choosing their partners wisely. This shows he understood how natural processes could lead to changes over time.

Monboddo thought that early humans were wild, lived alone, and ate plants. He believed that modern people suffered from many illnesses because they were no longer living in nature.

His Unique Personality

Burnett was known for being quite unusual. He always rode his horse between Edinburgh and London instead of taking a carriage. Another time, after a court decision about a horse went against him, he refused to sit with the other judges. Instead, he sat below the bench with the court clerks!

In 1787, when he was 71, he was visiting a court in London. Part of the floor started to collapse, and everyone rushed out. But Monboddo, who was partly deaf and couldn't see well, was the only one who didn't move. When asked why, he said he thought it was "an annual ceremony" that didn't involve him.

In his younger years, Burnett suggested that the orangutan was a type of human. At that time, "orangutan" was a general term for all kinds of apes. He might have believed a naval officer's report that described a group of monkeys as human. Monboddo believed that humans were not just creatures of reason, but creatures who could *learn* to reason, even if it was a slow and difficult process.

He once said that all humans must have been born with tails that were removed by midwives. His friends made fun of him for this, and he took back the idea later. But some people now see this as him thinking about how species change. He seemed to argue that animals adapted to survive, and his ideas about how apes became humans were a form of evolutionary theory. Monboddo also believed that children found living in the wild were still human and could learn to think. He thought orangutans were human because his sources said they could feel shame.

See also

In Spanish: Lord Monboddo para niños

In Spanish: Lord Monboddo para niños