James Tod facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Lieutenant-Colonel

James Tod

|

|

|---|---|

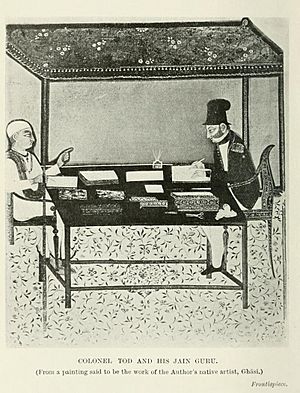

The frontispiece of the 1920 edition of Tod's Annals and Antiquities of Rajast'han

|

|

| Born | 20 March 1782 |

| Died | 18 November 1835 (aged 53) London

|

| Occupation | Political agent, historian, cartographer, numismatist |

| Employer | East India Company |

|

Notable work

|

|

| Spouse(s) |

Julia Clutterbuck

(m. 1826–1835) |

| Children |

|

| Parent(s) |

|

Lieutenant-Colonel James Tod (born March 20, 1782 – died November 18, 1835) was a British officer. He worked for the British East India Company. He was also a scholar who studied the history and geography of India.

Tod used his official job and his hobbies to write many books. These books were about India, especially the area called Rajputana. Today, this area is known as Rajasthan. Tod often called it Rajast'han.

Tod was born in London and grew up in Scotland. He joined the East India Company's army in 1799. He quickly moved up in rank. He became a captain and worked with a royal court in India.

After a war called the Third Anglo-Maratha War, Tod became a Political Agent. His job was to help unite parts of Rajputana under the East India Company. During this time, he gathered most of the information for his books.

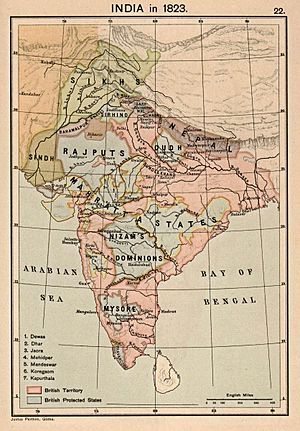

Tod was good at his job at first. But other people in the East India Company questioned his methods. His work was limited, and his areas of control became smaller. In 1823, because of health issues, Tod left his job and went back to England.

In England, Tod published several books about Indian history and geography. His most famous book was Annals and Antiquities of Rajast'han. He wrote it using the notes he took during his travels. He left the army in 1826. That same year, he married Julia Clutterbuck. James Tod died in 1835 when he was 53 years old.

Contents

James Tod's Early Life and Career

James Tod was born in Islington, London, on March 20, 1782. He was the second son of James and Mary Tod. His family was well-known. He went to school in Scotland, but we don't know exactly where. His family had a long history in Scotland. Some of his ancestors even fought with Robert the Bruce, a famous Scottish king. Tod was proud of this history. He felt a strong connection to the brave values of those times.

Many Scots at that time looked for adventure. Tod joined the British East India Company. He studied at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich. In 1799, he left England for India. Other family members, including his father, had also gone to India. His father had owned a farm there.

Tod started as a young officer in the Bengal Army. He became a lieutenant in 1800. By 1805, he was part of an escort for an important British official. This official worked at a royal court in India. By 1813, Tod became a captain and led this escort.

The royal court often moved around the kingdom. As they traveled, Tod studied the land and its geology. He used his training as an engineer. He also hired others to help him with this work. In 1815, he created a map. He gave this map to the Governor-General of India, the Marquis of Hastings.

This map of "Central India" became very important for the British. Soon after, the Third Anglo-Maratha War began (1817-1818). During this war, Tod worked in the intelligence department. He used his knowledge of the region to help the British. He also planned military strategies.

James Tod as a Political Agent

In 1818, James Tod became a Political Agent. This meant he worked for the British government in western Rajputana. The British East India Company had made agreements with the Rajput rulers. This allowed the British to have indirect control over the area.

An old book about Tod says he worked hard to fix the problems in Rajputana. He helped repair damage from invaders. He also tried to heal old family fights. His goal was to rebuild society in the region.

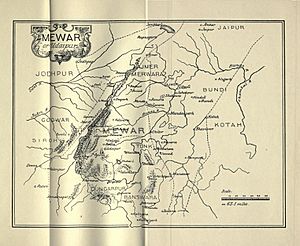

Tod continued his surveying work. This area was dry, mountainous, and challenging. His responsibilities grew quickly. He first worked in Mewar, Kota, Sirohi, and Bundi. Soon, he also took on Marwar. In 1821, he was given charge of Jaisalmer too. These areas were important. They acted as a protective zone against possible Russian advances from the north.

Tod believed that Rajput states should only have Rajput people. He thought this would make the areas more stable. This would also stop outside forces from influencing the people. He asked Charanas (bards) to create a list of the 'Thirty Six Royal Races of Rajasthan'. Tod's teacher, Yati Gyanchandra, led this group.

Tod had many successes. He helped bring peace back to the region. Within a year, many deserted towns and villages were filled with people again. Trade improved. Even with lower taxes, the government collected more money than ever before. For five years, Tod earned the respect of the local leaders and people. He helped several royal families, including the Ranas of Udaipur. They had been ruined by Maratha raiders.

Challenges and Return to England

Not everyone in the East India Company respected Tod. His boss, David Ochterlony, was worried about Tod's quick success. He also felt Tod did not talk to him enough. One Rajput prince complained about Tod's deep involvement in his state. This led to Marwar being removed from Tod's control.

In 1821, Tod favored one side in a royal dispute. This went against his orders. He received a strong warning. His power was limited, and he had to consult Ochterlony more. Kota was also taken from his control. In 1822, Jaisalmer was removed too. Officials worried that he was too sympathetic to the Rajput princes.

These losses of power made Tod feel his reputation was too damaged. He felt he could no longer work well in Mewar, the only area he still controlled. He resigned his job as Political Agent in Mewar that year. He said it was due to poor health.

A bishop named Reginald Heber wrote about Tod. He said that the government in Calcutta suspected Tod of corruption. They reduced his powers. But later, they realized their suspicions were wrong.

In February 1823, Tod left India for England. He took a long route through Bombay for his own enjoyment.

Later Life and Legacy

In his last years, Tod gave talks about India in Paris and other European cities. He joined the new Royal Asiatic Society in London. He even worked as their librarian for a while. In 1825, he had a stroke because he worked too much. He left the army the next year, after being promoted to lieutenant-colonel.

He married Julia Clutterbuck in 1826. They had three children: Grant Heatly Tod-Heatly, Edward H. M. Tod, and Mary Augusta Tod. Tod's health had been poor for most of his life. He died on November 18, 1835, soon after returning to England from Italy. He was 53. He had another stroke on his wedding anniversary, and died 27 hours later.

Tod's View of the World

Historians have studied James Tod's ideas. He saw the Rajputs as natural friends of the British. This was because both groups had struggled against the Mughal and Maratha states. Some historians believe Tod's ideas influenced British policy in western India for over a century.

Tod liked the idea of Romantic nationalism. This idea suggests that each state should have only one main community. Because of this, he wanted to remove Marathas and other groups from Rajput lands. He also helped create treaties to redraw the borders of different states. Before his time, some borders were unclear. Tod wanted clearer lines between the states, and he succeeded.

Tod also believed that British rule had simply replaced Maratha rule. He thought this stopped the Rajputs from becoming true nations. He was one of the people who created "indirect rule." In this system, princes managed local affairs but paid tribute to the British for protection. However, he also criticized this system. He felt it prevented the Rajput states from becoming truly independent.

Tod wrote in 1829 that indirect rule led to "national degradation" for the Rajput areas. He believed this weakened them. He questioned if allies who couldn't rule themselves could be trusted. He wondered if they might turn against the British if they had a chance.

Tod saw the Muslim Mughals as harsh rulers and the Marathas as greedy. But he thought the Rajput social system was like the feudal system in medieval Europe. He also felt their way of telling history was like the poets of the Scottish Highlanders. He believed there was a system of checks and balances between rulers and their lords. He also noted their family feuds and a peasant class.

Tod thought the Rajputs were on the same path of development as European nations like Britain. He used these ideas in his books. He suggested that British people and Rajputs had a shared history. He even thought they might have a common ancestor from long ago. He believed this could be proven by comparing their myths and legends.

Later, in the 1880s, another British administrator named Alfred Comyn Lyall disagreed with Tod. Lyall said that Rajput society was tribal, based on family ties, not feudal. If Rajput society was not feudal, then it wasn't on the same path as European nations. This meant there was no need to think they should become independent states.

Tod loved bardic poetry. This showed the influence of Sir Walter Scott's books about Scotland. Tod rebuilt Rajput history using old Rajput texts and stories. He also used philology (the study of language in historical sources) to learn about parts of Rajput history that even the Rajputs didn't know. He used religious texts called Puranas for this.

James Tod's Published Works

His most famous work is Annals and Antiquities of Rajast'han.

New Editions of His Works

The Royal Asiatic Society is working on a new edition of the Annals. This is to celebrate the Society's 200th birthday in 2023. A team of experts is preparing the original text. They are also adding new introductions and notes. A companion book will also be published. It will help people understand this important text. It will include extra pictures and old documents. This new edition is being published by the Society and Yale University Press.

See also

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |