Jean-Baptiste Henri Lacordaire facts for kids

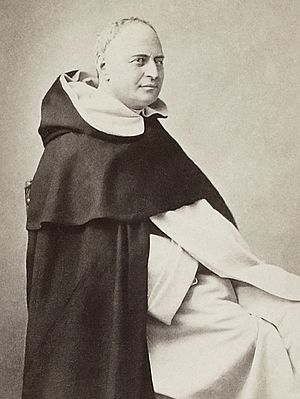

Jean-Baptiste Henri-Dominique Lacordaire (born May 12, 1802 – died November 21, 1861) was a famous French priest, speaker, writer, and thinker. He was also a political activist. He is well-known for bringing back the Dominican Order (a group of Catholic priests and brothers) to France after the French Revolution. Many people thought Lacordaire was the best speaker from a church pulpit in the 1800s.

Contents

Early Life and Studies

Henri Lacordaire was born in Recey-sur-Ource, France, on May 12, 1802. His father was a doctor in the French navy. Henri was raised in Dijon by his mother, Anne Dugied, after his father died in 1806. He had three brothers, and one of them, Jean Théodore Lacordaire, became a scientist who studied insects.

Henri was raised Catholic but stopped practicing his faith during his studies at the Dijon Lycée (a type of high school). He then went on to study law. He was very good at public speaking in Dijon, where he joined a group of young people interested in politics and literature. Here, he learned about ideas that supported the Pope's strong authority. These ideas slowly made him less interested in the Enlightenment thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau. However, he still believed in individual freedoms and the ideals of the 1789 French Revolution.

In 1822, he moved to Paris to finish his law studies. Even though he was too young to argue cases in court, he was allowed to do so and won several cases. A famous lawyer named Berryer noticed his talent. But Lacordaire felt lonely and bored in Paris. In 1824, he returned to Catholicism and soon decided to become a priest.

With help from the Archbishop of Paris, Monseigneur de Quélen, Lacordaire started studying at a religious school called Saint-Sulpice in 1824. His mother and friends were not happy about his choice. He continued his studies in Paris, but he later said the education there was not very good. He wrote that people sometimes thought he was "mad" during his time at the seminary.

In 1827, he became a priest for the Archdiocese of Paris. He first worked as a chaplain for a convent of nuns. The next year, he became a chaplain at Lycée Henri-IV. This experience made him realize that many young French people in public schools were losing their faith.

Working for God and Freedom

Feeling discouraged, Lacordaire almost went to the United States to be a missionary. But the French Revolution of 1830 kept him in France. He met Father Hugues Felicité Robert de Lamennais, a leading Catholic thinker. Lacordaire had not always agreed with Lamennais, but in May 1830, Lamennais convinced him to support a mix of strong papal authority and liberal ideas. This meant supporting the Pope's power while also believing in modern freedoms.

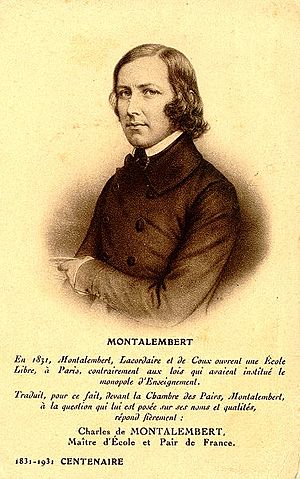

Lacordaire, Lamennais, and their friend Charles de Montalembert supported the July Revolution in France. They wanted the new laws of 1830 to be fully followed. They also supported other freedom movements in countries like Poland, Belgium, and Italy. On October 16, 1830, they started a newspaper called L'Avenir (which means "The Future"). Its motto was "God and Freedom!" In a time when many people were against the Church, the newspaper tried to combine Catholic faith with democratic ideas.

They asked for freedom of the press (the right to publish without government control), freedom to form groups, and the right for more people to vote.

They also strongly supported freedom of education. Lacordaire believed that if the government controlled schools, it would harm religious teaching. He thought many students lost their faith after leaving school. He was against the government having a monopoly (total control) over universities. On May 9, 1831, Lacordaire and Montalembert opened a free school, but the police closed it two days later. Lacordaire defended himself in court but could not stop the school from being permanently shut down.

Lacordaire was especially strong in his demand for the Church and State to be separate. He urged French priests to refuse the salary paid by the government. He wanted the clergy to live simply, like the early apostles. On November 15, 1830, he said, "Freedom is not given, it is taken." These demands, along with his criticism of bishops appointed by the new government, caused a scandal among French bishops. Most of these bishops supported the French king and local church authority, not the Pope's absolute power. The strong words in L’Avenir led the French bishops to put Lamennais and Lacordaire on trial. But they were found not guilty.

In December 1830, the editors of L’Avenir created the General Society for the defense of religious freedom. They stopped publishing L’Avenir on November 15, 1831. Lacordaire, Lamennais, and Montalembert, known as the "Pilgrims of Freedom," went to Rome to ask Pope Gregory XVI for support. They hoped to present their ideas to him. At first, they felt hopeful, but they soon became disappointed by the Pope's cool welcome. On August 15, 1832, the Pope condemned their ideas in a letter called Mirari Vos. He did not name them directly, but he clearly spoke against their demands for freedom of conscience and freedom of the press.

Even before this condemnation, Lacordaire started to distance himself from his friends. He returned to Paris and continued his work as a chaplain. On September 11, he published a letter saying he would obey the Pope's judgment. He then convinced Montalembert to do the same. In 1834, he also challenged Lamennais, who refused to accept the Pope's decision. Lamennais left the priesthood and wrote a book criticizing the kings and priests. Pope Gregory quickly condemned Lamennais's book. This event made it difficult for new, modern ideas to be openly discussed in Catholic circles for a long time. Lacordaire further separated himself from Lamennais. He expressed his sadness about the results of the 1830 Revolution and said he would remain loyal to the Church. He criticized Lamennais for being too proud and trying to put human authority above the Church's.

Powerful Preaching

In January 1833, Lacordaire met Madame Swetchine, who became a good friend and helped him calm down some of his strong ideas. She was a Russian woman who had become Catholic and had a famous meeting place in Paris where many important people gathered. He wrote many letters to her, forming a close friendship.

In January 1834, Father Lacordaire began giving a series of talks at the Collège Stanislas, encouraged by Frédéric Ozanam, who started the Society of Saint Vincent de Paul (a charity group). These talks were very popular, even beyond his students. Lacordaire was known as the greatest church speaker of the 1800s. His speeches were not just about asking people to repent; they were also about defending the Catholic faith. He showed that someone could be a French citizen and a Catholic at the same time.

The Archbishop of Paris asked Lacordaire to give a series of Lenten talks in 1835 at the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris. These talks were especially for young Christians. Lacordaire's first talk was on March 8, 1835, and it was a huge success. About 6,000 people attended, making it a major social event. Because of this success, he was asked to speak again the next year. Historians say Lacordaire's Notre Dame talks were "one of the most dramatic events of nineteenth century church history." Today, his talks are still praised for bringing new life to traditional church sermons, mixing theology, philosophy, and poetry.

Among those who listened to his talks in 1836 was Marie-Eugénie de Jésus de Milleret. Meeting Lacordaire changed her life and led her to start a religious group called the Religious of the Assumption. Years later, she wrote to Lacordaire, saying, "Your words gave me a faith which henceforth nothing could shake."

However, even after his great success, Lacordaire faced growing criticism about his religious views. Then, his mother died. Lacordaire felt he needed to study theology more deeply, so he went to Rome to study with the Jesuits. While there, he published a "Letter on the Holy See," where he strongly repeated his belief in the Pope's supreme authority. This disagreed with the Archbishop of Paris, who believed in the authority of the local French church.

Bringing Back the Dominicans to France

In 1837, Lacordaire saw how another priest, Prosper Guéranger, had brought back the Benedictine Order. Lacordaire decided to join the Dominican Order himself and bring them back to France. This meant giving up some personal freedoms, but he felt it was important.

Pope Gregory XVI and the head of the Dominicans supported his plan. The Pope even gave him a convent in Rome to train new French Dominicans. In September 1838, Lacordaire returned to France to find people who wanted to join and to get financial and political support. He wrote a powerful message in a newspaper, saying that religious orders could fit with the ideas of the French Revolution, especially because the Dominicans had a democratic structure. He said that their vow of poverty was like a strong application of the revolutionary ideas of equality and brotherhood.

On April 9, 1839, Lacordaire officially joined the Dominicans in Rome and took the name Dominic. He made his final promises on April 12, 1840. In 1841, he returned to France wearing the Dominican habit, which was technically against the law at the time. On February 14, 1841, he preached at Notre-Dame in Paris. He then started several Dominican convents, beginning in Nancy in 1843. In 1844, he bought an old monastery and turned it into a training center for new Dominicans. He also influenced two Canadians who brought the Dominican Order to Canada.

In 1850, the Dominican Province of France was officially re-established under his leadership, and he was chosen as its head. However, Pope Pius IX appointed Alexendre Jandel, who had different ideas than Lacordaire, as the head of the entire Dominican Order. Jandel believed in a very strict interpretation of the old Dominican rules, while Lacordaire had a more liberal view. They had a disagreement in 1852 about prayer times in the convents. Lacordaire preferred a more relaxed schedule to allow for preaching and teaching. In 1855, the Pope supported Jandel, making him the general master of the Order. After a period without administrative duties, Lacordaire was re-elected head of the French province in 1858.

Later Years

Lacordaire's later years were marked by political disagreements and internal disputes within the Dominican order. He had long been against the July Monarchy (the government at the time) and supported the Revolution of 1848. With Frédéric Ozanam, he started a newspaper called L'Ère Nouvelle (The New Era). This paper campaigned for the rights of Catholics under the new government. Their ideas combined traditional Catholic beliefs in freedom of conscience and education with social justice for workers. Lacordaire was elected to the National Assembly (the French parliament) from the Marseille region. He sat on the far left side of the Assembly, supporting the Republic. However, he resigned on May 17, 1848, after workers' riots and an invasion of the Assembly. He chose to step down rather than take sides in what he thought would be a civil war. When L'Ère Nouvelle started supporting more socialist ideas, he left the paper's leadership on September 2, but he continued to support its goals.

Lacordaire supported the revolutions in Italy in 1848 and later the French invasion of the Papal States (lands ruled by the Pope). He wrote to Montalembert, "We must not at all be too alarmed by the possible fall of Pius IX." He was disappointed by the Falloux Laws, even though they tried to give some freedom to Catholic secondary education. Lacordaire was against the election of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte and condemned his takeover of power on December 2, 1851. He then retired from public life. He later explained, "My hour had come to disappear with the others. Many Catholics followed another line... and threw themselves with ardor before absolute power. This split... has always been a great mystery to me and a great sadness."

In his semi-retirement, he focused on educating young people, which was allowed by the Falloux Laws. In July 1852, he became the head of a school in Oullins, near Lyon. Then, in 1854, he took a similar role at the school of Sorèze. Finally, on February 2, 1860, he was elected to the Académie française, a very respected French institution. He took the seat of Alexis de Tocqueville, a famous writer and thinker. His election was seen as a quiet protest by the Académie and Catholics against Napoléon III, who had allowed some Italian states to leave the Papal States and join with independent Piedmont. Encouraged by those who opposed the Emperor, Lacordaire agreed not to criticize Napoléon III's actions in Italy. So, his acceptance into the Académie was not controversial.

Around this time, he said his famous last words: "I hope to die a penitent religious man and an unrepentant liberal." This meant he hoped to die as a faithful Catholic who was sorry for his sins, but also as someone who never stopped believing in freedom and liberal ideas.

Lacordaire only attended the Académie once. He died at the age of 59 on November 21, 1861, in Sorèze, where he was also buried.

Quotes

- "Between the strong and the weak, between the rich and the poor, between the lord and the slave, it is freedom which oppresses and the law which sets free."

- "It is not genius, nor glory, nor love that reflects the greatness of the human soul; it is kindness."

- "The words of freedom are large among a people who do not know its extent."

Works

His most important publication was a collection of his Conférences de Nôtre Dame de Paris (talks given at Notre Dame).

- Eloges funèbres (speeches honoring Antoine Drouot, Daniel O'Connell, and Mgr Forbin-Janson)

- Lettre sur le Saint-Siège (Letter on the Holy See)

- Considérations sur le système philosophique de M. de Lamennais (Thoughts on the philosophical system of Mr. de Lamennais)

- De la liberté d'Italie et de l'Eglise (On the freedom of Italy and the Church)

- Conferences (translated vol. I only, London, 1851)

- Dieu et l'homme in "Conférences de Notre Dame de Paris" (God and Man in "Notre Dame Conferences") (translated London, 1872)

- Jésus-Christ (Jesus Christ) (translated London, 1869)

- Dieu (God) (translated London, 1870)

- Henri Perreyve, ed., Letters, 8 vols. (1862), translated Derby, 1864, revised and enlarged ed. London, 1902

Sources

- Edward McSweeny, "Lacordaire on Property," The Catholic World, Vol. 45 (1887).

- Margaret Oliphant, "Henri Lacordaire," Blackwood's Magazine, Vol. 93 (1863).

- Peter M. Batts, Henri-Dominique Lacordaire's Re-Establishment of the Dominican Order in Nineteenth-Century France, The Edwin Mellen Press, 2004

- Peter M. Batts, "Jean-Baptiste Henri Lacordaire" in New Catholic Encyclopedia (2003)

- Thomas Bokenkotter, Church and Revolution: Catholics and the Struggle for Democracy and Social Justice (NY: Doubleday, 1998)

- T.B. Scannell, "Jean-Baptiste-Henri Dominique Lacordaire" in The Catholic Encyclopedia (1910)

See also

In Spanish: Jean-Baptiste Henri Lacordaire para niños

In Spanish: Jean-Baptiste Henri Lacordaire para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |