Jean-Baptiste Morin (mathematician) facts for kids

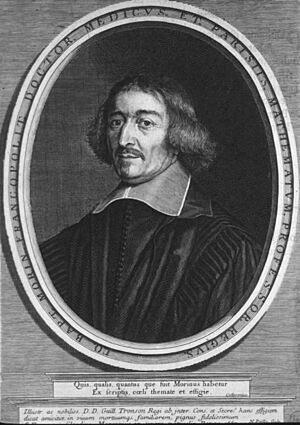

Jean-Baptiste Morin (born February 23, 1583 – died November 6, 1656) was a smart French scientist. He was a mathematician, an astrologer, and an astronomer. He was also known by his Latin name, Morinus.

Contents

Life and Early Work

Morin was born in a town called Villefranche-sur-Saône in France. When he was 16, he started studying philosophy. Later, in 1611, he began studying medicine and became a doctor two years after that.

From 1613 to 1621, Morin worked for the Bishop of Boulogne. During this time, he traveled to Germany and Hungary. He helped the bishop as an astrologer. He also visited mines and learned about metals. After this, he worked for the Duke of Luxembourg until 1629.

Morin was very interested in optics, which is the study of light and vision. He also kept studying astrology. He even worked with another famous astronomer, Pierre Gassendi, to observe the stars.

Professor of Mathematics

In 1630, Morin got an important job. He became a professor of mathematics at the Collège Royal in Paris. He taught there for the rest of his life.

Morin's Scientific Views

Morin strongly believed that the Earth stayed still in space. This idea is called the geocentric model. Because of this, he disagreed with Galileo, who said the Earth moved around the Sun. Morin continued to argue against Galileo's ideas even after Galileo's famous trial.

Morin also disagreed with the ideas of another famous thinker, Descartes, after they met in 1638. These disagreements sometimes made Morin feel alone in the scientific world.

Morin thought it was important to find better ways to solve problems in geometry, especially with shapes on a sphere. He also believed that scientists needed more accurate tables to track the Moon's position.

Morin and the Longitude Problem

One of Morin's biggest goals was to solve the longitude problem. Knowing longitude helps sailors find their exact east-west position at sea. In 1634, he suggested a way to do this. His idea was to measure the Moon's position compared to the stars. This was a new version of a method first suggested by Johann Werner in 1514.

Morin improved this method by suggesting better scientific tools. He also thought it was important to consider something called lunar parallax. This is how the Moon's position seems to shift depending on where you are on Earth.

Morin did not think that using clocks to find longitude would work. He famously said, "I do not know if the Devil will succeed in making a longitude timekeeper but it is folly for man to try."

Evaluating Morin's Idea

Because there was a prize for solving the longitude problem, a group was formed to check Morin's idea. Important people like Étienne Pascal were on this committee. Morin argued with this committee for five years. His idea was seen as difficult to use in practice.

To try and convince them, Morin suggested building an observatory. This would help get very accurate information about the Moon. Even though he argued a lot, in 1645, he was given a pension (a regular payment) for his work on the longitude problem.

Morin and Astrology

Morin was perhaps most famous for his work as an astrologer. Near the end of his life, he finished a huge book called Astrologia Gallica. This means "French Astrology." It was a very long and complex book written in Latin. It was published in 1661, after he had passed away.

The book had 26 parts and was 850 pages long. It covered many types of astrology, like natal astrology (about a person's birth chart), Judicial astrology (about future events), and Mundane astrology (about world events). Parts of his book have been translated into other languages.

Morin was known for trying to predict events very carefully using a person's birth chart. He used techniques like "directions" and "solar and lunar returns." He also thought that "transits" (how planets move in the sky now) were important for timing events.

Morin questioned many older ideas in astrology, even those from famous astrologers like Ptolemy. He wanted to create a clear set of tools for astrology. He also promoted a new technique called in mundo directions, which was possible because of new math discoveries. Morin showed examples where his methods helped explain events very well.

Jean-Baptiste Morin died in Paris when he was 73 years old.

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |