Johannes R. Becher facts for kids

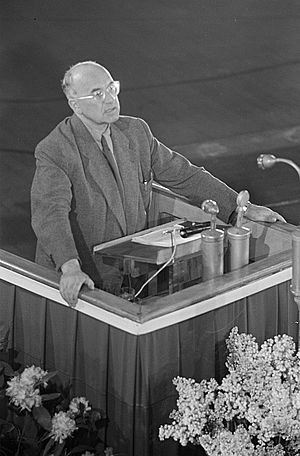

Johannes Robert Becher (born May 22, 1891 – died October 11, 1958) was a German politician, writer, and poet. He was involved with the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) before World War II. For a while, he was part of a modern art movement called expressionism.

When the Nazi Party rose to power in Germany, many modern art styles were stopped. Becher escaped a military raid in 1933 and lived in Paris for some years. He then moved to the Soviet Union in 1935 with the KPD's main group. After Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, Becher and other German communists were moved to a safe place in Tashkent.

He became important again in 1942 and was called back to Moscow. After World War II ended, Becher left the Soviet Union. He returned to Germany and settled in the area that later became East Berlin. As a KPD member, he was given many important jobs in culture and politics. He also became a leader in the Socialist Unity Party. In 1949, he helped start the DDR Academy of Arts, Berlin. He was its president from 1953 to 1956. In 1953, he received the Stalin Peace Prize, which was later called the Lenin Peace Prize. He was the culture minister for the German Democratic Republic (GDR) from 1954 to 1958.

Contents

Early Life of Johannes R. Becher

Johannes R. Becher was born in Munich, Germany, in 1891. His father, Heinrich Becher, was a judge. Johannes went to local schools.

From 1911, he studied medicine and philosophy at colleges in Munich and Jena. He later stopped his studies to become an expressionist writer. His first works were published in 1913.

Political Activities in Germany

Becher was very active in communist groups. In 1917, he joined the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany. Then, in 1918, he moved to the Spartacist League. This group later became the Communist Party of Germany (KPD). In 1920, he left the KPD because he was disappointed with the German Revolution's outcome. He returned to the KPD in 1923 and worked very hard for the party.

His art entered an expressionist phase during this time. He was part of die Kugel, an art group in Magdeburg. He also published his writings in magazines like Verfall und Triumph, Die Aktion, and Die neue Kunst.

In 1925, the government reacted strongly to his anti-war novel. It was called (CHCI=CH)3As (Levisite) oder Der einzig gerechte Krieg. He was accused of "literary high treason" because of it. This law was changed in 1928.

That year, Becher helped start the Association of Proletarian-Revolutionary Authors. This group was connected to the KPD. He was its first leader and helped edit its magazine, Die Linkskurve. From 1932, Becher became a publisher for the newspaper Die Rote Fahne. In the same year, he was chosen to represent the KPD in the Reichstag, which was the German parliament.

Escaping the Nazis

After the Reichstag fire, Becher was put on a Nazi blacklist. However, he managed to escape a large police raid in Berlin in 1933. With help, he traveled to Brno and then to Prague.

He then traveled to Zurich and Paris. He lived in Paris for a while among many other Germans who had left their country. A Hungarian artist named Lajos Tihanyi painted his portrait there, and they became friends.

Finally, in 1935, Becher moved to the USSR. Other KPD members also moved there. In Moscow, he became the main editor of a German magazine for people who had left Germany. He was also chosen as a member of the KPD's Central Committee. Becher faced challenges during this time. From 1936, he was not allowed to leave the USSR.

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact of 1939 was a treaty between Germany and the Soviet Union that worried German communists. After Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, the government moved German communists to safe places inside the country. Becher was moved to Tashkent. This city became a safe place for many Russians and Ukrainians escaping the war.

While in Tashkent, he became friends with Georg Lukács, a Hungarian philosopher. They studied old literature together. After this, Becher changed his writing style from modernism to Socialist Realism.

Becher was called back to Moscow by 1942. In 1943, he helped start the National Committee for a Free Germany.

Returning to East Germany

After World War II, Becher returned to Germany with a KPD group. He settled in the Soviet-controlled part of Germany. There, he was given many cultural and political jobs. He helped set up the Cultural Association to "bring German culture back to life." He also started the Aufbau-Verlag publishing house and the literature magazine Sinn und Form. He also wrote for the funny magazine Ulenspiegel.

In 1946, Becher was chosen for the main committees of the Socialist Unity Party. After the German Democratic Republic (GDR) was formed on October 7, 1949, he became a member of the Volkskammer, which was its parliament. He also wrote the words for "Auferstanden aus Ruinen," which became the national anthem of the GDR.

That year, he helped create the DDR Academy of Arts, Berlin. He was its president from 1953 to 1956, taking over from Arnold Zweig. In January 1953, he received the Stalin Peace Prize in Moscow. This prize was later renamed the Lenin Peace Prize.

In Leipzig in 1955, the German Institute for Literature was founded. It was first named in Becher's honor. The institute's goal was to train writers who supported socialism. Famous writers who graduated from there include Erich Loest and Volker Braun.

From 1954 to 1958, Becher was the Minister of Culture of the GDR. Later in his life, his political standing became less strong, and he was demoted in 1956.

In his final years, Becher began to question some of his earlier beliefs. His book Das poetische Prinzip (The Poetic Principle) was published in 1988.

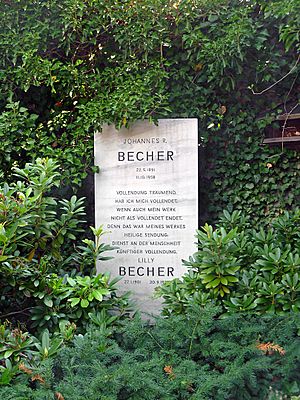

In September 1958, Becher's health was getting worse, so he gave up all his jobs. He died from cancer on October 11, 1958, in an East Berlin hospital. Becher was buried in the Dorotheenstadt cemetery in central Berlin. His grave is considered a special "grave of honor" in Berlin.

Legacy and Honours

After his death, his political party praised Becher as a "great German poet." However, some younger East German writers, like Katja Lange-Müller, thought his work was old-fashioned.

Here are some of the awards and honors he received:

- 1953 Stalin Peace Prize (later renamed the Lenin Peace Prize)

- The Institut für Literatur Johannes R. Becher was founded in 1955 in Leipzig and named after him.

Works

- Der Ringende. Kleist-Hymne. (1911)

- Erde, novel (1912)

- De profundis domine (1913)

- Verfall und Triumph (1914)

- Erster Teil, Poetry

- Zweiter Teil. Versuche in Prosa.

- Verbrüderung, Poetry (1916)

- An Europa, Poetry (1916)

- Päan gegen die Zeit, Poetry (1918)

- Die heilige Schar, Poetry (1918)

- Das neue Gedicht. Auswahl (1912–1918), Poetry (1918)

- Gedichte um Lotte (1919)

- Gedichte für ein Volk (1919)

- An alle!, Poetry (1919)

- Zion, Poetry (1920)

- Ewig im Aufruhr (1920)

- Mensch, steh auf! (1920)

- Um Gott (1921)

- Der Gestorbene (1921)

- Arbeiter, Bauern, Soldaten. Entwurf zu einem revolutionären Kampfdrama. (1921)

- Verklärung (1922)

- Vernichtung (1923)

- Drei Hymnen (1923)

- Vorwärts, du rote Front! Prosastücke. (1924)

- Hymnen (1924)

- Am Grabe Lenins (1924)

- Roter Marsch. Der Leichnam auf dem Thron/Der Bombenflieger (1925)

- Maschinenrhythmen, Poetry (1926)

- Der Bankier reitet über das Schlachtfeld, Narrative (1926)

- Levisite oder Der einzig gerechte Krieg, Novel (1926)

- Die hungrige Stadt, Poetry (1927)

- Im Schatten der Berge, Poetry (1928)

- Ein Mensch unserer Zeit: Gesammelte Gedichte, Poetry (1929)

- Graue Kolonnen: 24 neue Gedichte (1930)

- Der große Plan. Epos des sozialistischen Aufbaus. (1931)

- Der Mann, der in der Reihe geht. Neue Gedichte und Balladen., Poetry (1932)

- Der Mann, der in der Reihe geht. Neue Gedichte und Balladen., Poetry (1932)

- Neue Gedichte (1933)

- Mord im Lager Hohenstein. Berichte aus dem Dritten Reich. (1933)

- Es wird Zeit (1933)

- Deutscher Totentanz 1933 (1933)

- An die Wand zu kleben, Poetry (1933)

- Deutschland. Ein Lied vom Köpferollen und von den „nützlichen Gliedern“ (1934)

- Der verwandelte Platz. Erzählungen und Gedichte, Narrative and Poetry (1934)

- Der verwandelte Platz. Erzählungen und Gedichte, Narrative and Poetry (1934)

- Das Dritte Reich, Poetry illustrated by Heinrich Vogeler (1934)

- Der Mann, der alles glaubte, Poetry (1935)

- Der Glücksucher und die sieben Lasten. Ein hohes Lied. (1938)

- Gewißheit des Siegs und Sicht auf große Tage. Gesammelte Sonette 1935–1938. (1939)

- Wiedergeburt, Poetry (1940)

- Die sieben Jahre. Fünfundzwanzig ausgewählte Gedichte aus den Jahren 1933–1940. (1940)

- Abschied. Einer deutschen Tragödie erster Teil, 1900–1914., Novel (1940)

- Deutschland ruft, Poetry (1942)

- Deutsche Sendung. Ein Ruf an die deutsche Nation. (1943_

- Dank an Stalingrad, Poetry (1943)

- Die Hohe Warte Deutschland-Dichtung, Poetry (1944)

- Dichtung. Auswahl aus den Jahren 1939–1943. (1944)

- Das Sonett (1945)

- Romane in Versen (1946)

- Heimkehr. Neue Gedichte., Poetry (1946)

- Erziehung zur Freiheit. Gedanken und Betrachtungen. (1946)

- Deutsches Bekenntnis. 5 Reden zu Deutschlands Erneuerung. (1945)

- Das Führerbild. Ein deutsches Spiel in fünf Teilen. (1946)

- Wiedergeburt. Buch der Sonette. (1947)

- Lob des Schwabenlandes. Schwaben in meinem Gedicht. (1947)

- Volk im Dunkel wandelnd (1948)

- Die Asche brennt auf meiner Brust (1948)

- Neue deutsche Volkslieder (1950)

- Glück der Ferne – leuchtend nah. Neue Gedichte, Poetry (1951)

- Auf andere Art so große Hoffnung. Tagebuch 1950. (1951)

- Verteidigung der Poesie. Vom Neuen in der Literatur. (1952)

- Schöne deutsche Heimat (1952)

- Winterschlacht (Schlacht um Moskau). Eine deutsche Tragödie in 5 Akten mit einem Vorspiel. (1953)

- Der Weg nach Füssen, Play (1953)

- Zum Tode J. W. Stalins (1953)

- Wir, unsere Zeit, das zwanzigste Jahrhundert (1956)

- Das poetische Prinzip (1957)

- Schritt der Jahrhundertmitte. Neue Dichtungen, Poetry (1958)

See also

In Spanish: Johannes R. Becher para niños

In Spanish: Johannes R. Becher para niños