John B. Fenn facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John B. Fenn

|

|

|---|---|

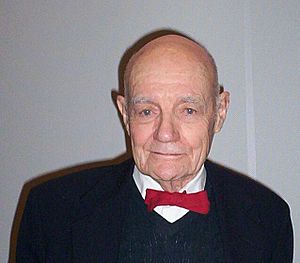

Fenn in 2005

|

|

| Born |

John Bennett Fenn

June 15, 1917 New York City, U.S.

|

| Died | December 10, 2010 (aged 93) |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Berea College Yale University |

| Known for | Electrospray ionization |

| Awards | Humboldt Prize (1982) Thomson Medal (2000) ABRF Award (2002) Nobel Prize in Chemistry (2002) Wilbur Cross Medal (2003) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Chemistry |

| Institutions | Princeton University Yale University Virginia Commonwealth University |

John Bennett Fenn (June 15, 1917 – December 10, 2010) was an American professor who studied chemistry. He won a share of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2002.

Fenn shared half of the award with Koichi Tanaka. They were recognized for their work with mass spectrometry. This is a way to measure the mass of tiny particles. The other half of the prize went to Kurt Wüthrich.

Fenn helped create a method called electrospray ionization. This method is very useful for studying large molecules. It is also used in many labs today. Earlier in his career, Fenn researched jet engines and molecular beams. He wrote over 100 scientific papers and one book.

Fenn was born in New York City. His family moved to Kentucky during the Great Depression. He went to Berea College and earned his PhD from Yale University. He worked for companies and research labs. Later, he taught at Yale and Virginia Commonwealth University.

Contents

Early Life and School

John Fenn was born in New York City. He grew up in Hackensack, New Jersey. His father worked different jobs before the Great Depression. One job was as a draftsman at an aircraft company.

Fenn remembered sitting in the cockpit of Charles Lindbergh's famous plane, Spirit of St. Louis. He was ten years old and pretended to fly it. When the Depression hit, his family moved to Berea, Kentucky. His aunt, who taught at Berea College, helped them.

Fenn finished high school at 15. He took extra classes for another year. He earned his bachelor's degree from Berea College. He also took summer classes at the University of Iowa and Purdue University.

When Fenn thought about graduate school, a professor told him to take more math classes. He had not taken many math courses before. Even with his later success, Fenn felt his math skills were a challenge. He got offers from Yale University and Northwestern University. He chose Yale.

Fenn studied physical chemistry at Yale. He earned his PhD in chemistry in 1940. His thesis was 45 pages long, but only three pages were written words.

Research and Teaching Jobs

After graduate school, Fenn first worked for Monsanto. He worked with chemicals there. In 1943, he and a colleague left Monsanto. Fenn then worked at a small company called Sharples Chemicals.

In 1945, he joined a new research company called Experiment, Inc. Fenn published his first scientific paper in 1949. This was ten years after he finished graduate school. This was unusual for scientists at the time.

In 1952, Fenn went to Princeton University. He became the director of Project SQUID. This program supported research on jet engines. During this time, Fenn started working on supersonic atomic and molecular beams. These are now used a lot in chemistry research.

Fenn returned to Yale University in 1967. He worked in both the chemistry and engineering departments. He did much of his research in Mason Laboratory. In 1987, Fenn reached Yale's required retirement age. He became a professor emeritus. This meant he still had an office. However, he lost most of his lab space and research helpers.

After a disagreement with Yale, Fenn moved to Richmond, Virginia. He joined Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU). He became an analytical chemistry professor there. VCU started an engineering department in the late 1990s. Fenn taught in both departments until he passed away. Even in his 80s, Fenn loved being in the lab. He said he liked to "mingle and exchange with the young people."

Important Discoveries

Fenn did not start his Nobel-winning research until later in his career. He was semi-retired when he first published his work on electrospray ionization. This method is used for mass spectrometry.

Fenn felt his work got a big boost when proteomics became popular. Proteomics is the study of proteins. In 2001, over 1,700 papers on proteomics were published. Many of them used electrospray ionization.

Electrospray ionization helps scientists quickly find the mass of large molecules. It works even when many different molecules are mixed together. A liquid sample is sprayed into a special source. It then forms tiny droplets. These droplets evaporate in a vacuum. This makes the droplets carry more electrical charge. For large molecules like proteins, this makes them easier to measure.

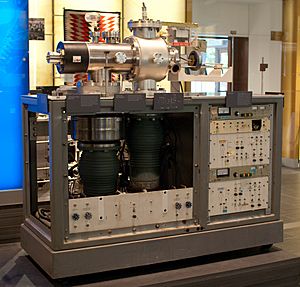

Even though he started publishing later, Fenn had over 100 papers. He also wrote a book called Engines, Energy, and Entropy: A Thermodynamics Primer. The Chemical Heritage Foundation Museum in Philadelphia has the instrument Fenn built. It was used to develop electrospray ionization.

Dispute Over His Invention

Fenn's work with electrospray ionization led to a legal disagreement. It was between him and his former employer, Yale University. The problem started in 1987. This was when Fenn turned 70, Yale's mandatory retirement age.

Yale made Fenn an emeritus professor. This meant he had less lab space. Emeritus professors at Yale get an office. However, they cannot run their own research labs. In 1989, Yale asked Fenn about his electrospray work. He said it didn't have much value.

Fenn believed he owned the rights to his invention. He patented the technology himself. He then sold licenses to a company he partly owned. In 1993, another company wanted to use the technology. They found out Fenn held the patent. Yale then discovered this.

Yale's rules say that a part of any money from patents goes to the university. This money helps fund future research. Yale does not claim rights to inventions made outside the university. Fenn said he owned the technology. He argued he did the work after he had to reduce his lab space.

Yale made its own licensing deal with a company. So, Fenn sued the university in 1996. Yale sued him back. They asked for money and for the patent to be given to them. They tried to settle out of court, but couldn't.

In 2005, a judge ruled against Fenn. The judge ordered Fenn to pay Yale money from royalties and legal fees. The judge said Fenn had not been honest with the university.

Yale was happy with the decision. But some people connected to Yale were disappointed. They felt it was not right to treat a Nobel Prize winner this way. Fenn had worked at the school for a very long time.

Awards and Honors

Nobel Prize

Fenn shared the 2002 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He shared it with Koichi Tanaka and Kurt Wüthrich. They won for finding ways to identify and study large biological molecules.

Fenn and Tanaka shared half the award. Their work helped use mass spectrometry to study big biological molecules. Wüthrich was honored for his work with nuclear magnetic resonance. This method studies similar molecules in liquid.

Fenn was honored mainly for his work on electrospray ionization. This made it possible to study large molecules with mass spectrometry. His Nobel lecture was called "Electrospray Wings for Molecular Elephants." He was surprised to win. He said, "It's like winning the lottery, I'm still in shock." When he won, Fenn was working at Virginia Commonwealth University.

Other Awards

Fenn received his Nobel Prize late in his career. Before that, he won many other awards. Early on, his research focused on molecular beams. He was named an honorary president for a molecular beam symposium in 1977. In 1985, he became the first fellow of the International Molecular Beam Symposium. In 1982, he received an award from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

Later, his work in mass spectrometry earned him more awards. In 1992, the American Society for Mass Spectrometry gave him an award. The International Society of Mass Spectrometry gave him the Thomson Medal in 2000. That same year, the American Chemical Society gave him an award for advances in chemical tools. In 2002, he won the Association of Biomolecular Resource Facilities Award. In 2003, his old school, Yale, gave him the Wilbur Cross Medal. This is the highest honor from the Yale Graduate School Alumni Association.

Fenn was a member of many professional groups. These included the American Chemical Society and the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. In 2000, he became a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 2003, he was elected to the National Academy of Sciences.

Personal Life

Fenn married Margaret Wilson during his second year of graduate school. They had three children: two daughters and a son. Margaret died in a car accident in New Zealand in 1992. Fenn later married Frederica Mullen.

He passed away in Richmond, Virginia, on December 10, 2010. He was 93 years old. This was exactly eight years after he received his Nobel Prize. Fenn was survived by Frederica, his three children, seven grandchildren, and eleven great-grandchildren.

See also

In Spanish: John B. Fenn para niños

In Spanish: John B. Fenn para niños