John Scott Russell facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Scott Russell

|

|

|---|---|

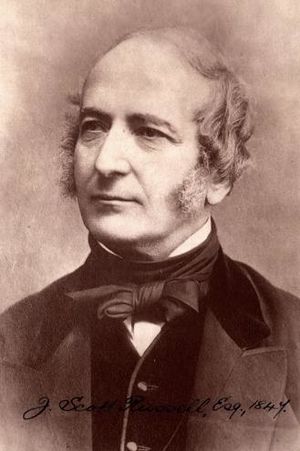

John Scott Russell in 1847

|

|

| Born | 9 May 1808 |

| Died | June 8, 1882 (aged 74) Ventnor, Isle of Wight, England

|

| Nationality | British |

| Education | University of Edinburgh, University of St. Andrews, University of Glasgow |

| Occupation | Engineer |

| Spouse(s) | Harriette Russell (née Osborne) |

| Children | Osborne Russell, Norman Scott Russell, Louisa Scott Russell, Mary Rachel Scott Russell, Alice M. Scott Russell |

| Parent(s) | David Russell and Agnes Clark Scott |

| Engineering career | |

| Institutions | Royal Society of Edinburgh (Councillor 1838-9), Royal Society, Institution of Civil Engineers (Vice President), Institution of Naval Architects (Vice President), Society of Arts (Secretary 1845-50) |

| Awards | Keith Prize |

John Scott Russell (born May 9, 1808, in Parkhead, Glasgow, Scotland – died June 8, 1882, in Ventnor, Isle of Wight, England) was a brilliant Scottish civil engineer, ship designer, and shipbuilder. He is famous for working with Isambard Kingdom Brunel to build the huge ship Great Eastern.

Russell also made an amazing discovery about waves, which he called the "wave of translation." This discovery led to the modern study of solitons, which are special types of waves. He also created a new way to design ships called the "wave-line system." Besides his engineering work, he helped organize the Great Exhibition of 1851, a huge event that showed off new inventions and art.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

John Russell was born on May 9, 1808. His parents were Reverend David Russell and Agnes Clark Scott. He first studied at the University of St. Andrews. Later, he moved to the University of Glasgow. While there, he added his mother's maiden name, Scott, to his own. This is how he became John Scott Russell.

He finished university in 1825 when he was just 17 years old. After graduating, he moved to Edinburgh. There, he taught math and science at the Leith Mechanics' Institute. He was a very popular teacher, and his classes had the most students in the city.

In 1832, a professor at the University of Edinburgh passed away. Even though Scott Russell was only 24, he was chosen to teach temporarily. He was very good at science and a popular lecturer. He decided to focus on engineering and doing large-scale experiments.

Family and Home Life

In 1839, John Scott Russell married Harriette Osborne in Dublin. They had two sons and three daughters. Their home in Sydenham Hill, London, became a lively place. This was especially true after Russell and his friends moved Paxton's famous glass building from the Great Exhibition to the Crystal Palace nearby.

The American engineer Alexander Lyman Holley became good friends with Scott Russell and his family. Holley often visited their home in Sydenham. Because of this friendship, Holley and his colleague Zerah Colburn traveled on the first trip of the Great Eastern from Southampton to New York in 1860. Scott Russell's son, Norman, even stayed with Holley in Brooklyn. Norman also went on that first voyage, though John Scott Russell himself did not.

His son, Norman, followed in his father's footsteps. He became a naval architect, just like his dad. Norman also helped with the Institution of Naval Architects, which his father had helped create.

Early Inventions: The Steam Carriage

While living in Edinburgh, John Scott Russell worked on steam engines. He designed a special square boiler. He found a new way to make the boiler's surface strong, which became a common method.

In 1834, a company called the Scottish Steam Carriage Company was formed. They built a steam carriage with two powerful engines. Six of these carriages were made that year. They were very comfortable and well-built. Starting in March 1834, these carriages ran between Glasgow and Paisley. They traveled at about 15 miles per hour.

However, some people who managed the roads didn't like the steam carriages. They thought the carriages damaged the roads. They even put logs and stones in the road to stop them. This made it harder for all carriages, even horse-drawn ones. Sadly, in July 1834, one of the steam carriages overturned. Its boiler broke, and some passengers died. After this, two of the coaches were sent to London. They ran for a short time between London and Greenwich.

The Amazing Wave of Translation

In 1834, John Scott Russell was doing experiments. He wanted to find the best shape for canal boats. During these tests, he saw something incredible. He described it as the wave of translation. Today, scientists call this wave Russell's solitary wave.

He spent a lot of time studying these waves. He even built special tanks at his home to watch them. He noticed some very important things about them:

- These waves are very stable. They can travel long distances without changing much. Normal waves usually flatten out or break apart.

- The speed of these waves depends on how big they are. Their width depends on the water's depth.

- Unlike regular waves, they don't combine when they meet. A smaller wave will just be overtaken by a larger one.

- If a wave is too big for the water's depth, it splits into two waves, one big and one small.

Scott Russell's observations were new and exciting. At first, some scientists found it hard to believe his findings. This was because his observations didn't fit with the existing theories about water waves. But over time, other scientists, like Lord Rayleigh and Joseph Valentin Boussinesq, did mathematical work that supported Scott Russell's observations.

It wasn't until the 1960s, with the help of modern computers, that the full importance of Scott Russell's discovery became clear. His work is now very important in physics, electronics, biology, and especially in fibre optics. This led to the modern understanding of solitons.

It's important to know that true solitons keep their shape and speed even after crashing into other solitons. The solitary waves on water that Scott Russell saw are not exactly true solitons. After they interact, they change slightly, and a small ripple is left behind.

Designing Better Ships: The Wave-Line System

After studying his "wave of translation," Russell wanted to find the best ship hull shape. He wanted a shape that would move through water with the least resistance. He believed that a good design would efficiently push water out of the way and then let it fill back in smoothly.

He used special tools called dynamometers to measure resistance carefully. He found that a specific curved shape, like a "versed sine wave," was ideal for the front of the ship.

At first, he thought the back of the ship could be a mirror image of the front. But he soon realized that water moving away from the back of a ship behaved differently. So, he designed the stern (back) to be rounded, with a shape like a "catenary."

His studies completely changed how merchant and navy ships were designed. Before him, most ships had rounded bows to carry more cargo. But starting in the 1840s, "extreme clipper ships" began to have concave (curved inward) bows. This design was also used for steamships, leading up to the famous Great Eastern.

Observing the Doppler Effect

John Scott Russell was one of the first people to observe the Doppler effect in an experiment. He published his findings in 1848. The Doppler effect explains how the frequency of a wave (like sound or light) changes if the source or the observer is moving. For example, a siren sounds higher pitched as it comes towards you and lower pitched as it moves away.

Working with Professional Groups

Throughout his life, Russell was very involved in scientific and professional groups. These groups were becoming very important during his time.

In 1844, there was a big boom in railway building. Russell had written an article about steam engines and steam navigation for an encyclopedia. He was offered a job as an editor for a new newspaper called the Railway Chronicle in London.

The next year, he became the secretary for a committee. This committee was set up by the Royal Society of Arts to organize a national exhibition. This led to the famous Great Exhibition of 1851. Russell worked very hard on this event. He helped get manufacturers and shopkeepers to show their products. The exhibition was a huge success!

Russell became a member of the Institution of Civil Engineers in 1847. He often attended meetings and shared his ideas. He was elected to its council in 1857 and became a vice-president in 1862. He was also elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1849.

In 1860, a meeting at his house led to the creation of the Institution of Naval Architects. Russell was one of its vice-presidents. In 1864, he published a massive three-volume book called The Modern System of Naval Architecture. This book showed the designs of many new ships being built.

After he passed away, people said that he helped turn naval architecture from an art into a precise science. He gave the first big push to making ship design truly scientific.

Building Great Ships

Around 1838, Scott Russell worked at a shipyard in Greenock. There, he started using his wave-line system for Royal Mail ships. He also introduced many other new ideas. In 1848, he bought his own shipbuilding company, the Millwall Iron Works in London.

He built two ships for Isambard Kingdom Brunel that were meant to travel to Australia. These ships, Adelaide and Victoria, were similar in size to Brunel's SS Great Britain.

Brunel thought that even larger ships were needed for long voyages. He asked Scott Russell to be his partner in building the Great Eastern. Brunel had the original idea for the ship, its strong cellular structure, and the use of both paddle wheels and a screw propeller. But the ship also used Scott Russell's ideas, like the wave-line shape and his special way of building the ship lengthwise.

The Great Eastern project had many challenges. Scott Russell's initial cost estimate was too low, which caused financial difficulties for him. However, he managed to finish the work. Brunel insisted on launching the ship sideways, even though Russell preferred a dry dock. The Great Eastern was finally launched in 1858.

During the 1850s, Russell argued that the Navy should build iron warships. Some people say that the first design for an iron warship, HMS Warrior, was a "Russell ship."

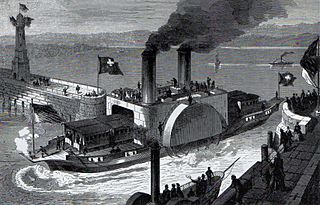

In 1868, Scott Russell designed a special train ferry for Lake Constance in Europe. This ferry, called the Bodensee Trajekt, started service in 1869. It was the world's first train ferry to cross a lake. The ferry had to be designed so it wouldn't go too deep in the water. Russell achieved this by making the ship's upper structure carry the weight of the train. Later, he used this design for a cross-channel ferry that could handle the shallow harbor of Dover, but that project wasn't built until 1933.

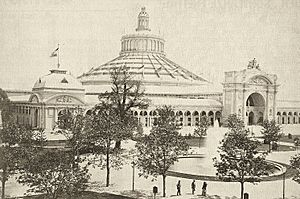

The Vienna Rotunda: A Grand Design

Even though his design for the Great Exhibition wasn't chosen, Scott Russell did design a magnificent building for the 1873 Vienna Exposition. This building was called the Rotunde. It was 108 meters (about 354 feet) across. For nearly a century, it was the largest dome in the world! It had no supports inside to block the view. Many people consider it his greatest achievement in structural engineering.

Honors and Awards

In 1838, John Scott Russell received the gold Keith Medal from the Royal Society of Edinburgh. He earned this award for his paper about how water resists moving objects.

In June 1849, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. This was a great honor, given for his important papers on the "great Solitary Wave" and his work with the British Association.

In 1995, an aqueduct that carries the Union Canal over the Edinburgh Bypass was named the Scott Russell Aqueduct. This is the same canal where he first saw his famous "wave of translation." Also in 1995, scientists were able to create the hydrodynamic soliton effect again, very close to where John Scott Russell first saw it in 1834.

A building at Heriot-Watt University is named after him. In 2019, he was added to the Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame.

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |