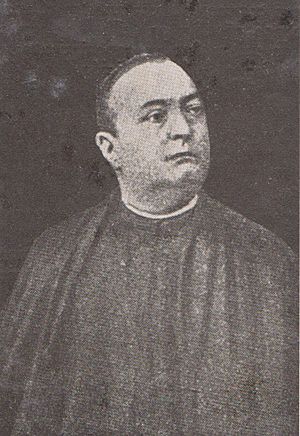

José Roca y Ponsa facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

José Roca y Ponsa

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

José Roca y Ponsa

1852 Vic, Spain

|

| Died | 1938 Las Palmas, Spain

|

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | religious |

| Known for | priest, theorist |

| Political party | Carlism |

José Roca y Ponsa (1852–1938) was a Spanish Catholic priest. People also knew him as "Magistral de Sevilla." He became famous in 1899 because of a disagreement between two important church leaders.

In the early 1900s, he was a key figure in big discussions about religion and politics. Today, many see him as a strong supporter of traditional religious beliefs. Roca worked as a lecturing canon in cathedrals in Las Palmas (1876-1892) and Seville (1892-1917). He also helped run church newspapers and wrote many small books. He was one of the few well-known Spanish church figures who openly supported the Carlist movement. He also liked the Integrist ideas of Traditionalism.

Contents

Early Life and Education

José Roca y Ponsa came from an old Catalan family. His father, Cayetano Roca Subirachs (1828-1918), was from Vic. He was a businessman who owned or ran a corset factory. His mother was Engracia Ponsa. José had at least one brother, Cayetano, and two sisters, Dolores and Margarita.

José grew up in a very religious home. He started his church education at the local seminary in Vic in 1861. A seminary is a school where people train to become priests. He spent his teenage years there, preparing for religious service. His studies stopped suddenly when the queen, Isabella II, lost her throne in the Glorious Revolution.

Moving to the Canary Islands

Some stories say that in the early 1870s, José was involved in the Carlist movement. This group wanted a different king for Spain. Because of this, he was forced to leave Spain.

In 1872 or 1873, Roca y Ponsa and three other students moved to a seminary in Las Palmas. This city is in the Canary Islands. He finished his theology degree there in 1873. He became a deacon in 1874 and a priest in 1875. His first Mass was on March 27, 1875.

He worked as a priest in the village of Artenara in the Canary Islands. In 1876, he became a parish priest there. The same year, he earned degrees in canon law in Granada. Canon law is the law of the church. He then returned to the Canary Islands to teach at the Las Palmas seminary. He taught subjects like Latin, philosophy, Hebrew, and theology. In 1876, he also became a lecturing canon at the Las Palmas Cathedral.

Church Career and Influence

In Las Palmas, Roca y Ponsa continued to serve as a lecturing canon and a professor at the seminary. He also started managing new church newspapers. He began to gain recognition. In 1877, the bishop of the Canary Islands chose him to lead a church trip to Rome. Roca also took on important roles during local church events.

His position grew stronger when a new bishop, José Proceso Pozuelo, arrived in 1879. In 1881, the bishop asked him to help solve a sensitive issue about the local cemetery. Around this time, Roca started a short-lived church newspaper and then a bi-weekly paper. He managed these until 1888. His strong articles against the liberal government led to a trial. In 1885, he was sentenced to live away from Las Palmas for 3.5 years, but it is not clear if this sentence was carried out. In 1890, Roca became the head of the Seminary of Canarias.

Moving to Seville

By the early 1890s, Roca was known in Las Palmas as a great speaker. For reasons that are not clear, he decided to leave the islands. He applied for a position as a canon at the Seville cathedral. In 1892, he became a canon there, and in 1893, he took on the role of lecturing canon.

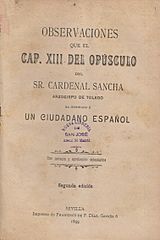

His first years in Andalusia were quiet. He was mainly known for his regular sermons. Things changed in 1899 when Roca became famous across Spain. This happened after he published a pamphlet criticizing the teachings of the primate, Cardinal Sancha. People wrongly thought that the Seville archbishop approved this criticism. This caused a big scandal and a widespread debate.

As a well-known person, he was active in Catholic meetings in the early 1900s. Even though he became very famous, Roca did not advance much in his church career. This was especially true after 1911, when his new booklets caused a negative reaction from the Vatican. Besides being a lecturing canon, he only took on some new teaching jobs at the local seminary and other places.

In the mid-1910s, Roca began to step back from active church service. In 1914, he had a serious accident that caused ongoing health problems. When he reached the regular retirement age, he resigned from his canon position. In 1917, he joined the Congregation of Priests of Saint Philip Neri, an order for retired priests.

Roca continued to give sermons in Seville churches less often. In 1925, he celebrated 50 years as a priest. He was a member of many religious groups. In the late 1920s, he took on leadership roles in some of them. However, his activity was limited by growing problems with his eyesight. His last sermons in Seville were in mid-1931. Around that time, he moved back to Las Palmas. His sister's family took care of him there. Even though he was half-blind, he performed some small local religious duties until the late 1930s.

Writer and Speaker

Roca first became known as a great speaker. In 1879, he was chosen to give important sermons at major religious events. By the early 1890s, he was well-known in Las Palmas for his sermons. This reputation grew even more during his 25 years in Seville. His sermons were passionate and strong. They were a mix of church teachings and arguments against modern ideas. Some of his sermons were later published as separate booklets.

Some people later praised Roca for making the ideas of great apologists (defenders of faith) popular. But they also noted that his "blunt and passionate words" meant he was a better speaker than a theorist. After 1910, Roca also spoke at non-religious events. These were often right-wing political gatherings. Some were scientific talks about famous people like Jaime Balmes and Marcelino Menendez Pelayo. Others were openly political conferences with a Traditionalist viewpoint.

Newspapers and Books

For about 15 years, Roca was the driving force behind several Catholic newspapers in the Canary Islands. These were either published by the bishop's office or related groups. In the early 1870s, he managed a paper called El Golgota. This paper went beyond a local church print. Thanks to Roca, El Golgota had reporters in France, England, and Italy.

In 1879, he started a church daily newspaper, El Faro Católico de Canarias. This paper probably did not last long. In 1881, Roca focused on a new bi-weekly paper called La Revista de las Palmas. This was a more successful project. A youth section, Los Jueves de la Revista, was added in 1885. Roca managed this publication until 1888.

After moving to Seville in 1899, Roca launched a church daily, El Correo de Andalucia. For a while, he was its main editor. In the 1900s, he actively took part in meetings called Asamblea Nacional de Buena Prensa. Until the early 1910s, he remained active in their Seville office. He checked Catholic papers to make sure they followed church teachings.

Between 1873 and 1935, Roca published about 15 booklets. These were either collections of essays, often based on his sermons, or short pamphlets. They usually focused on religion and politics. The author often gave his very critical opinion of Spanish public life. He also offered his own ideas for the future. Some booklets responded to specific issues or people. Others contained more general lessons.

Roca often used different pen-names that people could easily recognize. But he was best known as "Magistral de Sevilla." His later writings were published under his own name. The booklet that had the biggest impact and caused a national debate was Observaciones que el capitulo XIII del opúsculo del cardenal Sancha ha inspirado a un ciudadano español (1899).

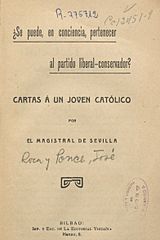

¿Se puede, en conciencia, pertenecer al partido liberal-conservador? (1912) and ¿Cuál es el mal mayor y cuál es el mal menor? (1912) also became well-known. This happened when the Vatican expressed doubts about his strong political views. Moderate Catholics quickly criticized them as "doctrines condemned by His Holiness."

His Beliefs and Views

Roca y Ponsa became famous mainly for his ideas about religion and politics. He believed that a society without one officially accepted and enforced religion could not be orderly or peaceful. In his view, Catholicism was the only correct religion. He thought it had shaped Spain for centuries and made the nation great. Catholic principles, he believed, should guide both the government and society.

He saw liberalism as the opposite of Catholicism. He thought it was not only useless as a political idea but also morally wrong. He blamed liberalism for Spain's decline and believed it would lead to more problems. Roca's view was common for some people in Spain. However, he expressed it in a very strong and uncompromising way. He saw politics as a battle between God and Satan.

He divided all political groups into two types: liberal and anti-liberal. Basically, only the Carlists and the Integrists were considered anti-liberal. All other parties, he thought, were part of the ungodly liberal group. Roca especially criticized the Conservatives. They accepted the government system of the Restoration. Although they claimed to support Christian people, he believed their hypocrisy actually weakened Christian values.

He blamed them for accepting a wrong idea of the lesser evil. He thought this idea actually opened the way for revolution. He also blamed some church leaders for this "malmenorismo" (choosing the lesser evil). His pamphlet against the primate, who told Catholics to "remain faithful and trust in the [liberal] government," caused a big national debate. This was especially true because Roca quoted the Pope's authority.

In the early 1900s, Roca tried to shape the growing Catholic political movement. This movement was forming at many Catholic meetings. He wanted it to be a strong, uncompromising force. He tried to make them reject the idea of "malmenorismo." In simple terms, this would mean taking a stand against the government. When he failed, he then said these meetings were doomed and based on wrong principles.

Even though classical Spanish liberalism was declining, Roca did not change his approach. For him, new radical ideas like socialism and republicanism were just extreme forms of liberalism. He believed that while absolutism was one person taking too much power, republicanism, nationalism, or socialism were also taking too much power, but in the name of specific groups. He also opposed social-Catholic and Christian-democratic movements. He thought these groups were designed to work within a liberal democratic system and had given up on uniting religious and political goals.

Support for Carlism

Roca was one of the few well-known Catholic Church figures who openly and consistently supported the Carlist cause. He learned about Carlism from his father. Vic, his hometown, was known as a center for Carlist and Integrist priests. So, Roca's passion for the cause grew during his seminary years. He was involved in a Carlist plot in the early 1870s, which forced him to move to the Canary Islands.

Under his management, El Golgota, a Catholic church newspaper, became very similar to local Las Palmas Traditionalist papers in the late 1870s. Roca's sermons and writings also became more and more filled with the Traditionalist view of religion and politics. He continued this approach in La Revista in the 1880s. This bi-weekly paper attacked Carlist groups that broke away and supported the strong anti-government stance of Ramón Nocedal.

However, in 1888, when Nocedal himself broke away from mainstream Carlism to form Integrism, Roca did not take sides. He remained neutral. Some sources call him a strong Integrist, others a stubborn Carlist. Some note that his move to Andalusia weakened both the Carlist and Integrist groups in the Canary Islands.

Later Involvement

During his time in the Canary Islands and Andalusia, Roca did not join Traditionalist political groups. However, after he moved back to the mainland Spain, his connections with the movement grew stronger. He wrote for the unofficial Carlist newspaper El Correo Español and other regional party papers, using pen-names. He helped start El Radical, a Seville newspaper for young Carlists. He traveled around the country, invited by young Carlists, and attended party dinners praising the Carlist leader Bartolomé Feliú. In return, various Carlist groups praised Roca as a great thinker and writer.

However, he also kept his Integrist connections. At some public conferences, he appeared with experts like Manuel Senante. He remained friends with Juan Olazábal and might have also written for the main Integrist daily, El Siglo Futuro.

Roca was a key attendee at a big Carlist meeting called Magna Junta de Biarritz in 1919. He gave one of his most important speeches there. His embrace with the Carlist claimant Don Jaime was one of the most memorable moments from the event. In 1920, Roca helped to re-organize a Catholic daily newspaper, El Correo de Andalucia. He hired Domingo Tejera as its manager, which helped Tejera become a Traditionalist editor. In 1924, Don Jaime gave Roca the Order of Prohibited Legitimacy.

In 1930, along with other Carlists, Roca spoke with Cardinal Segura. They were confused by Segura's statements, which seemed to support the Alfonsist group (another royalist group). The same year, Roca attended a large meeting of Andalusian Integrists. In the first elections of the Second Spanish Republic in 1931, he ran in Las Palmas as an independent Catholic candidate, but he lost badly. In the early 1930s, he was praised as a great expert for the Carlist cause. In 1934, the claimant Alfonso Carlos named him the second member of the Council of Traditionalist Culture. As part of this role, in 1935, he published at least one article in the Carlist intellectual magazine Tradición.

See also

In Spanish: José Roca y Ponsa para niños

In Spanish: José Roca y Ponsa para niños

- Carlism

- Integrism (Spain)

- Traditionalism (Spain)

Images for kids

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |