Juan Alfonso de Baena facts for kids

Juan Alfonso de Baena (born around 1380s, died about 1435) was a medieval Castilian poet and scribe. He worked for King Juan II of Castile. Baena was a converso, meaning he was Jewish but converted to Christianity.

He is most famous for putting together the Cancionero de Baena. This was a very important collection of poems from the Middle Ages. It includes poems by over 55 Spanish poets. These poems were written between 1426 and 1465, during the reigns of kings like Enrique II, Juan I, Enrique III, and Juan II.

Contents

About Juan Alfonso de Baena

His Early Life

We don't know a lot about Juan Alfonso de Baena's early life. He was born in the late 1300s in a town called Baena in Córdoba, Spain. His parents were Jewish.

Research by José Manuel Nieto Cumplido shows that Baena's father was named Pero López. Juan Alfonso grew up in the old Jewish part of Baena. This research also found out about his family, including his wife, children, and nephew. His wife was Elvira Fernández de Cárdenas. They had at least two children, one named Juan Alfonso de Baena (like him) and another named Diego de Carmona. His nephew, Antón de Montoro, was also a poet.

Baena got his last name from his hometown. It was common for people to take their last names from where they lived. This also happened when conversos took Christian names. Baena likely converted from Judaism to Christianity around 1391. This was a time when many Jewish people converted because of attacks called pogroms.

From his own poems, we know Baena was educated in Baena. In one poem, he wrote:

I read inside Baena, / where I learned to make scribbles / and eat capers / many times for supper.

—Juan Alfonso de Baena, Cancionero de San Román

Working for the King and His Death

After his education, Baena worked as a tax collector and government worker in the early 1400s. Later, he got a job at the court of King Juan II. This is where he put together his famous Cancionero de Baena.

At the king's court, he was a "chamber scribe," which meant he was a royal government worker. He also worked part-time as a jester, someone who made the court laugh. This job suggests his family might have been from a middle-class background.

Sometimes, Baena fell out of favor with the king. This might have happened because his funny poems sometimes criticized court life too much. Because of these times, he never became more than a court scribe. However, his Cancionero became the most important book of poems from Juan II's court.

Juan Alfonso de Baena died during the later years of Juan II's rule. For a long time, no one knew exactly when he died. But in 1979, new writings were found that suggest Baena died in 1435.

His Jewish Background

We can tell Baena was Jewish from his own writings. He and other court jesters often made fun of themselves to make the royal family laugh. Baena often joked about his "Jewishness." He would use common Jewish stereotypes for comedy.

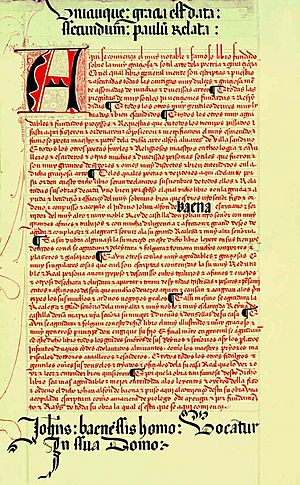

In the introduction to his Cancionero, Baena seriously wrote, "This book... was made, arranged, composed, and collected by the [Jewish] Juan Alfonso de Baena." He used the word judino, which was a rude term for a Jew. This shows that Baena himself openly identified with his Jewish background, even in formal writings.

Jester-poets like Baena also had "poetic debates." These were like rhyming battles where poets insulted each other for entertainment. Insults against Baena often mentioned his Jewish background. For example, some insults referred to eggplants. This vegetable became a common symbol for Jewish (and Muslim) food back then.

One poet, Rodrigo de Harana, insulted Baena by calling him an "apostate." This meant he was accusing Baena of having converted from his original faith. Most court jesters at this time were Jewish converts. These clues strongly suggest Baena's Jewish heritage, even without official documents.

Juan Alfonso de Baena's Works

The Cancionero de Baena

Cancioneros were collections of poems, like songbooks. They were very popular in Spain from the late 1300s to the mid-1400s. These songbooks first appeared in Galicia in the early 1200s.

At first, they collected Galician court poems. Later, they included poems in other languages and from more places. The poems in these cancioneros often used simple language. They talked about current events, people, and social customs. Poets also used them to argue, flatter, or complain. So, cancioneros give us a good look at what life was like in the royal courts. They saved many medieval poems.

Baena's Cancionero has 576 poems by 56 poets. These poems were written between the mid-1300s and mid-1400s. This period included the reigns of kings like Enrique II, Juan I, Enrique III, and Juan II.

Some people think Baena put the book together between 1426 and 1430. Others think it was later, in the 1440s. If Baena was the only one who added poems, the earlier dates are more likely. But research suggests that other people added poems after Baena died. So, the book was likely put together by Baena between 1426 and 1430. Other poems were added between 1449 and 1465.

Baena put the Cancionero together while working for King Juan II. He dedicated the book to the king. The Cancionero de Baena is the oldest collection of its kind in the Castilian language. It includes many of Baena's own poems, including his funny satires and poetic letters.

The Cancionero de Baena was important because it showed a shift. Before this, court poetry in Spain was mostly in Galician-Portuguese. Baena's book helped make Castilian the main language for court poetry.

Baena's cancionero didn't just collect court poems. It also included poems from less important places than the royal court. It even had more serious "intellectual poetry" that used symbols and hidden meanings. These poems talked about moral, philosophical, and political ideas. The book was not organized in a strict way. It included many different types of poems and themes. This makes it important because it gives us a more complete picture of medieval Castilian literature.

The three main types of poems in the book are:

- Love poems: These were called Canciones de amor. They were based on a French style of love poem.

- Poetic debates: These were poems where two or more poets argued with each other. They used fixed rhymes and meters. Baena included many of his own debate poems.

- Moralizing texts: These poems thought about death, luck, the fall of great people, and how human life is not important without God.

Baena's introduction to the Cancionero de Baena, called the Prologus, is also famous. It was the first introduction to a collection of poems that also served as literary criticism. It even inspired other writers to write similar introductions in Castilian.

In his introduction, Baena said that poetry was a courtly hobby that was good for the mind and helped people feel better. He also described what an ideal court poet should be like. He said this poet should be "divinely inspired, well-read and well-traveled, eloquent and witty." These were also qualities expected of courtiers in general. Baena also said that an ideal poet should be a lover, or at least pretend to be in love. He believed that being in love helped a person gain knowledge and create good poetry.

How the Book Was Published

The only surviving copy of the cancionero is in the National Library of France in Paris. This copy was made around 1465, which is 20 to 40 years after Baena first put it together.

The surviving copy was kept at El Escorial from the mid-1700s. Research suggests that this copy might have a different order of poems than Baena's original. It seems that other people changed the Cancionero after Baena died. The latest poems in the book were written as late as 1449. Baena probably did not include works by poets like González de Mendoza or Rodríquez del Padrón. His original work was likely more organized by time and theme.

In modern times, the cancionero became easier to read when it was first printed in 1851 in Madrid.

Other Works by Baena

Many of Baena's poems are not in his own cancionero. Some of his poems are in another collection called the Cancionero de San Román. One of his longest and most interesting poems, called Dezir, is in this book. It has 218 lines.

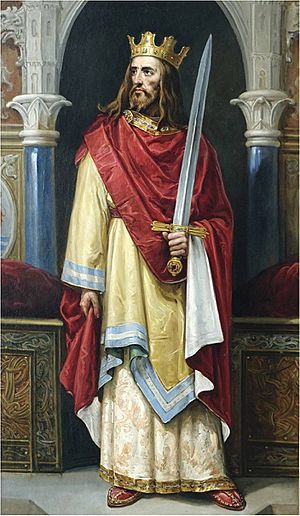

Unlike his funny poems in the Cancionero de Baena, Dezir is more serious. It is addressed to King Juan II. Baena praises the king and then gives him advice on how to make the country stronger. He suggests the king should fix corrupt local governments and unite the nation. This would help defeat threats from Muslim forces. Baena uses Alfonso VIII of Castile as an example of a king who successfully united the country and defeated enemies.

Dezir shows a different side of Baena. It proves he was not just a good collector of poems, a poet, and a jester. He also wrote serious political works, showing he had a deeper knowledge and intelligence than people might have thought.

Baena's Writing Style

Baena's writing style often used self-deprecating humor. This means he made fun of himself. He also mocked others. He had to do this without offending powerful people at court. Other poets at the time, like Villasandino and Baena's nephew Montoro, also used this style.

Baena would joke about his "own ugliness and dwarf-like stature." To be a successful jester, he had to do more than just be ugly. He had to "open wide the closet and reveal the skeleton within." This meant he had to make fun of his own Jewish background and former faith. Instead of hiding their Jewish roots, Jewish converts who were jesters were expected to joke about their past. This made the court laugh. Baena's style helped make his Jewish background seem less threatening. It turned it into funny stereotypes about big noses or different food habits.

Here is an example of Baena making fun of himself in the Cancionero:

Sir, I ate salmon and sea bass / and other fish of great kindness, / but know that vile fish / never entered my kitchen.

—Juan Alfonso de Baena, Cancionero de Baena

In this part, Baena jokes about the traditional Jewish diet. This diet does not allow shellfish or other bottom-feeding fish. He calls these "vile fish." But he mentions eating salmon and sea bass, which he calls "fish of great charm." Here, Baena uses both Jewish stereotypes and courtly ideas of high and low classes. He is clearly making fun of himself, but also, in a way, the court itself.

Baena was both an insider and an outsider at Juan II's court. This allowed him to use his position to joke about his own past. He also used humor to make fun of court life through funny characters and impressions. Sometimes, this led to him falling out of the king's favor.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Juan Alfonso de Baena para niños

In Spanish: Juan Alfonso de Baena para niños

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |