July 1936 coup d'état in Granada facts for kids

Quick facts for kids July 1936 coup d'état in Granada |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Spanish Civil War | |||||||

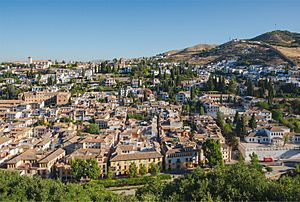

Granada, as seen from the Alhambra. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

The July 1936 coup d'état in Granada was a military uprising that happened in the city of Granada, Spain. This event was a key part of the start of the Spanish Civil War. On July 20, 1936, a group of military officers and their supporters took control of Granada.

The uprising began when soldiers in Granada rebelled against the government of the Spanish Republic. This happened after similar rebellions in other parts of Spain, like Spanish Morocco and Seville. In Granada, the military commander, General Miguel Campins, was forced to join the rebellion. Rebel troops and their allies quickly took over the city center. Important government officials, like the civil governor César Torres Martínez, were arrested. The rebels also captured the Armilla Airbase and other important locations.

However, many workers and people loyal to the Republic resisted. They gathered in the Albaicín neighborhood. The rebels used artillery to attack the Albaicín. After several days of intense fighting, the rebels took control of the neighborhood. With the fall of the Albaicín, the entire city of Granada was under rebel control. During these events, many people who resisted or were thought to resist were arrested or faced severe consequences. After Granada was taken, a strong crackdown began against those who supported the Republic.

Contents

Why the Uprising Happened

Granada's Political Situation

Before the uprising, Granada was a city with strong political disagreements. After the 1936 Spanish general election, where the Popular Front (a group of left-wing parties) won, tensions grew. Many conservative groups in Granada were unhappy with this result.

In March 1936, there were large protests and riots in Granada. Some buildings, like the Falange local and the Ideal newspaper office, were set on fire. Other places, including a theater and some churches, were also damaged. It's not clear who started all the fires, but these events caused a lot of anger and division among the people of Granada. The police were present but did not stop the incidents. These riots led to the dismissal of the civil and military governors.

Later, the election results for Granada were canceled, and a new election was held in May. The Popular Front won again, and conservative parties did not get any representatives. This made the Falange (a right-wing political group) stronger in Granada.

Planning the Coup

After the Popular Front's election victory, some military officers who opposed the Republic started planning an uprising. The government knew about these plans and tried to watch some officers in Granada. The civil governor, Ernesto Vega, was dismissed because of this. He was replaced by César Torres Martínez.

Granada was an important military center. It had an Infantry Regiment and an Artillery Regiment. Many officers from these regiments were involved in the secret plan. Colonels Basilio León Maestre and Antonio Muñoz Jiménez were key figures. Commander José Valdés Guzmán, who was also a member of the Falange, played a big role because he knew the local situation well.

Other groups also joined the plan. Some members of the Security and Assault Corps (a police force) and the Civil Guard were involved. The Falange in Granada also had many members ready to support the uprising.

Days Before the Uprising

On July 17, 1936, a military uprising began in Melilla, a Spanish city in North Africa. The next day, General Francisco Franco led an uprising in the Canary Islands.

On July 18, Granada was very tense. The military governor, General Campins, publicly said he was against the uprising in Morocco. He told Republican officials that his officers were loyal. However, he secretly sent a telegram to General Franco, offering his support.

That same day, the uprising spread to mainland Spain. In Seville, General Gonzalo Queipo de Llano took control of the city, though he faced strong resistance. In Cordoba, Colonel Ciriaco Cascajo also led an uprising and took over that city.

On July 19, Granada remained calm, but the tension was high. The civil governor, Torres Martínez, refused to give weapons to workers' groups who asked for them. He followed orders from the government not to arm the public. General Campins was ordered to send troops to Cordoba to stop the uprising there, but his officers were not willing to go. Captain Nestares, a conspirator, visited military barracks to encourage the rebels. That night, the plotters finalized their plans.

The Uprising Begins

On July 20, the military uprising in Granada was set to begin at 5:00 PM. Colonel Muñoz and Colonel León led the plan. Before the uprising, the head of the Guardia de Asalto, Captain Álvarez, agreed to join the rebels, which was a big help for the plotters.

Around 4:30 PM, the Popular Front Committee learned that troops were getting ready at the Artillery Barracks. The civil governor, Torres Martínez, called General Campins, who insisted his officers were loyal. But when Campins went to the barracks, he saw troops forming up and armed Falangists. He realized all his officers were part of the coup. Campins tried to leave, but his aides stopped him. He was then taken to the military command and forced to sign the declaration of war, officially starting the rebellion.

Taking Over the City Center

At 5:00 PM, troops led by Colonel Antonio Muñoz left their barracks and moved into the city center. Some people thought the soldiers were coming out to defend the Republic. The rebels set up artillery guns in important squares like Plaza del Carmen and Puerta Real. They also placed a battery on the road to El Fargue, which gave them a good position to shell the city.

The rebels quickly moved towards the Civil Government building. It was guarded by a small group of assault guards. Captain Nestares arrived at a nearby police station, and the police there joined the rebels. The assault guards at the Civil Government did not fire, and the rebels easily took over the building. They arrested Governor Torres Martínez, Virgilio Castilla Carmona (president of the Diputación), and Lieutenant Colonel Vidal Pagán (head of the Civil Guard).

At the same time, the urban police left the city hall and joined the rebels. Many city officials were captured when the rebels took over the building, including the mayor, Manuel Fernández Montesinos. A group of soldiers also occupied Radio Granada and began broadcasting the military declaration signed by General Campins every half hour.

Another important target was the Gunpowder and Explosives Factory of El Fargue, on the outskirts of Granada. This was the largest explosives factory in southern Spain. The rebels faced some resistance but quickly took control of the factory.

Other small areas of resistance in the city were quickly put down. The rebels took over all official buildings easily because supporters of the Popular Front had very few weapons and were disorganized. During the initial takeover of the city, only one rebel soldier was killed. Many workers and loyalists fled to the Albaicín neighborhood, where they put up a stronger fight.

Armilla Airfield

The Armilla Airbase, a few kilometers from Granada, was taken over by rebel soldiers and officers early in the morning without resistance. Three fighter planes sent from Madrid to help the loyalist forces in Granada arrived at Armilla but were immediately captured by the rebels.

Fighting in the Albaicín

The rebels did not immediately control the entire city. As night fell, resistance continued in the Albaicín neighborhood. Workers and loyalists built barricades at the entrances, especially at Carrera del Darro. The rebels realized they couldn't take the Albaicín by surprise. They brought in artillery, placing one battery at the Church of San Cristobal and another in the Alhambra, both overlooking the Albaicín. There were some initial shootouts, causing casualties on both sides.

On July 21, the artillery began firing on the Albaicín. Heavy fighting broke out, with defenders firing from balconies and rooftops, despite having few weapons. The rebels used infantry, assault guards, and Falangists to try and crush the resistance. Some defenders were captured, but the neighborhood continued to resist into the night. The radio repeatedly urged the defenders to surrender.

On July 22, Radio Granada issued an ultimatum. Women and children were given three hours to leave the neighborhood, while men were told to abandon their weapons and stay in their homes with white flags flying. If these orders were not followed, artillery would resume firing at 2:30 PM. Many women and children left, but the men continued to resist. The women were searched and sent to a temporary camp. The artillery then opened fire again. The captured fighter planes from Armilla also attacked the neighborhood, causing damage and casualties. Still, resistance continued after dark.

On July 23, the bombing of the Albaicín became even more intense. The defenders had suffered many casualties, and their ammunition was likely running out. White flags began to appear on balconies, and the rebels took this chance to enter the Albaicín. They quickly ended the resistance. Many defenders were captured, while some managed to escape to Republican areas near Guadix. A harsh crackdown against Republicans and leftists then began.

By the night of July 23, the rebels controlled all of Granada and its surrounding areas.

What Happened Next

Strategic Importance

By July 25, the uprising had succeeded in Granada, but the city was isolated within the Republican zone, as most of the province remained loyal to the Republic. This isolation became even clearer after the military rebellion failed in Málaga, which stayed with the Republic. The front line was very close to Granada, sometimes only eight kilometers from the city center.

In the first days, government forces bombed the city from the air. On July 30, a group of loyalist fighters tried to retake Granada but were pushed back by rebel forces. This was the only major attempt by the Republic to regain the city. Granada's isolation ended in mid-August when rebel forces from Africa managed to connect Granada with other rebel-controlled areas.

Even though it was surrounded, Granada had some advantages. Taking the El Fargue factory was very important because it produced many explosives for the rebel army throughout the war. Capturing the Armilla airfield was also crucial, as it allowed contact with other rebel zones and the arrival of reinforcements by air.

Repression and Consequences

Commander José Valdés Guzmán became the civil governor and was in charge of public order. He, along with Civil Guard lieutenant José Nestares and police chief Julio Romero Funes, was responsible for the crackdown in Granada.

Several groups were formed to carry out the repression, including the Escuadra Negra ("Black Squadron"). Many places were used as temporary detention centers. The Granada prison, designed for about 400 people, became severely overcrowded with over 2,000 prisoners. Many detainees were taken to the cemetery and faced severe consequences, often without a proper trial. August 1936 saw the highest number of such events. During the entire conflict, many people were arrested or faced severe consequences.

Many professionals, including doctors, lawyers, writers, artists, teachers, and especially workers, were among those who faced severe consequences. Several local public figures were also affected, such as Constantino Ruiz Carnero (writer and editor), Juan José de Santa Cruz (engineer), and Manuel Fernández Montesinos (the mayor at the time of the uprising). Along with the mayor, many city council members were affected. The University of Granada also suffered, with its rector and several professors facing severe consequences. However, the former civil governor, Torres Martínez, survived but was sentenced to a long prison term.

General Campins, the military commander, was dismissed and later sent to Seville, where he faced severe consequences.

The most famous person affected was the writer and poet Federico García Lorca. He had sought refuge with a Falangist family but was arrested and later faced severe consequences near Víznar. His death was widely reported internationally. While the harshness of the repression was known, many wealthy people in Granada tolerated these actions, believing them to be less serious than what was happening in Republican Spain.

See also

In Spanish: Golpe de Estado de julio de 1936 en Granada para niños

In Spanish: Golpe de Estado de julio de 1936 en Granada para niños

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |