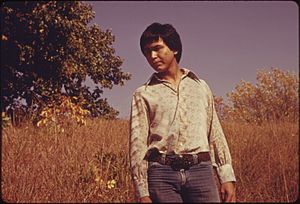

Kickapoo Tribe in Kansas facts for kids

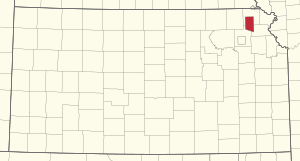

Location of Kickapoo Indian Reservation in Kansas

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,653 (2006) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, formerly Kickapoo | |

| Religion | |

| traditional tribal religion, Native American Church, Drum religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Kickapoo people and Fox, Sauk, and Shawnee people |

The Kickapoo Tribe of Indians of the Kickapoo Reservation in Kansas is one of three officially recognized tribes of Kickapoo people in the United States. Being "federally recognized" means the U.S. government has a special relationship with the tribe. This relationship gives the tribe certain rights and benefits.

Other Kickapoo tribes in the United States include the Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas and the Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma. There is also a group called the Tribu Kikapú in Mexico. They live near Múzquiz, Coahuila, and are related to the Oklahoma Kickapoo.

The Kansas Kickapoo Tribe runs many programs for its members. These include a Boys and Girls Club and a Head Start program for young children. They also have a Senior Center for elders and a health clinic. The tribe operates the Kickapoo Nation school, which teaches students from kindergarten through 12th grade.

Contents

Kickapoo Reservation in Kansas

The Kickapoo Indian Reservation in Kansas is located in Brown County. This area is in the northeastern part of Kansas. The reservation is about 5 miles by 6 miles in size. This covers an area of about 19,200 acres.

Kickapoo Language and Culture

Most members of the Kansas Kickapoo Tribe speak English today. In the past, they spoke the Kickapoo language. This language is part of the Algonquian language family. The word "Kickapoo" comes from their own language. It means "he moves from here to there." This name describes how the tribe often moved around.

Economic Growth

The Kickapoo Tribe in Kansas has developed several businesses. They own and operate the Golden Eagle Casino. This casino includes a buffet and a snack bar. It is located in Horton, Kansas. The tribe also manages a successful farm and ranch. These businesses help support the tribe and its programs.

Kickapoo History

The Kickapoo people have close ties to the Sac and Fox tribes. They were first recorded in history around 1667–1670. At that time, they lived near the Fox and Wisconsin Rivers. Over time, they moved south and west. They settled in areas like southern Michigan, northern Iowa, Ohio, and Illinois.

Early Treaties and Land Changes

The Kickapoo signed many treaties with the U.S. Government. These treaties often involved giving up their lands. For example, in 1803, they signed a treaty with several other tribes. This treaty gave up lands in the Ohio, Wabash, and Miami River areas. More treaties followed in the early 1800s. By 1820, the tribe had given up all their lands in the Wabash, White, and Vermilion Rivers. They then moved to Missouri near the Osage River.

Around 1832, the tribe gave up their lands in Missouri. They were given a "permanent" home in Kansas. This new home was south of the Delaware Nation near Fort Leavenworth. At the same time, some Kickapoo moved to Texas. The Spanish government invited them to settle there. They hoped the Kickapoo would help protect against American settlers.

After the Texas Revolution, these groups moved further south into Mexico. In 1854, the Kickapoo gave up the eastern part of their Kansas lands. This left them with about 150,000 acres. This treaty had two important parts. It allowed for a survey of Kickapoo lands. This survey could lead to individual land ownership. It also allowed a railroad to cross the reservation.

Land Allotment Challenges

Local agent William Badger wanted the Kickapoo lands to be divided. He wanted individual families to own their own plots. The tribe had always held their lands together. So, it is unlikely they truly wanted this change. However, Badger pushed for it. He was later replaced by Charles B. Keith in 1861.

Keith was an ally of Senator Samuel C. Pomeroy. Pomeroy was involved with the Atchison and Pike's Peak Railroad. This railroad wanted to cross the Kickapoo Reservation. They also wanted to buy any extra land after it was divided. In 1862, a new treaty was made. This agreement allowed chiefs to get 320 acres. Heads of households would get 160 acres. Other tribe members would get 40 acres. Most of the remaining 125,000 acres would be sold to the railroad.

When news of the treaty spread, many Kickapoo protested. They said they did not know the agreement had been finalized. They thought they were still negotiating. The Kansas Attorney General, Warren William Guthrie, started an investigation. The government paused the land division. A new Commissioner of Indian Affairs, William P. Dole, investigated further. Some frustrated Kickapoo decided to leave Kansas. About 700 people went to Mexico in 1864.

In 1865, the land division continued. But the tribe still resisted. By 1869, only 93 Kickapoo had accepted individual land ownership. Most preferred to keep their lands together. The Dawes Act of 1887 pushed for more land division. But the Kickapoo continued to resist. By 1938, only 75 of the 237 assigned land plots were still owned by tribal members.

Twentieth Century Challenges

After World War I, the U.S. faced the Great Depression. This was a time of great economic hardship. Kansas also suffered from a severe drought, known as the Dust Bowl. Temperatures were very high in the mid-1930s. In 1936, Kansas had its second hottest year ever. Reservation wells dried up, and livestock had to be sold. Gardens, which were a main food source, withered.

Kansas officials refused to give welfare help to Native people. They said they did not have enough money. Federal programs for Native Americans were often delayed. The Kickapoo Agent, George G. Wren, reported extreme poverty in 1933 and 1934. The tribe helped each other, and some work projects from the Indian Service provided relief.

Indian Reorganization Act

The Wheeler-Howard Act, also called the Indian Reorganization Act, became law in 1934. This law aimed to give Native tribes more control over their own affairs. It also aimed to reduce federal control. The Kickapoo Tribe created their own government under this act. They adopted a Constitution and By-Laws in 1937. This set up how the Kickapoo Tribal Council would be elected. The council included a Chairman, Vice-Chairman, Secretary, Treasurer, and three Councilmen.

Indian Claims Commission

In 1946, the Indian Claims Commission Act was passed. Its goal was to settle all old complaints tribes had against the U.S. government. These complaints included broken treaties or unfair land deals. Tribes had five years to file their claims. The Kickapoo Tribe of Kansas filed at least six claims. Some were on their own, and some were with other tribes.

The two largest awards were for "unconscionable consideration." This means the government paid too little for lands the tribe gave up. These awards came from treaties in 1854 and 1866. The money was approved in 1972. But there were appeals into the late 1970s. The U.S. government was trying to reduce the amount paid. This was because of costs from moving Mexican Kickapoo back to the U.S. in the 1860s and 1870s. The final plan for distributing the money was approved in 1980.

Threats to Tribal Status

From the 1940s to the 1960s, the U.S. government had a policy called "Indian termination." This policy aimed to end the special relationship with tribes. It also aimed to end reservations. Four Kansas tribes, including the Kickapoo, were targeted. The Kansas Act of 1940 was an early law in this period. It gave Kansas state courts power over crimes on reservations.

In 1953, the U.S. Congress passed House Concurrent Resolution 108. This resolution called for the immediate termination of several tribes. It also included all tribes in California, New York, Florida, and Texas. Termination meant losing all federal aid, services, and protection. It also meant the end of reservations. A memo in 1954 clarified that the "Potawatomi" mentioned included the Kickapoo Tribe in Kansas.

Because Kansas already had power over crimes, the government targeted the four Kansas tribes for quick termination. Hearings were held in 1954. Minnie Evans, a leader of the Prairie Band of Potawatomi Nation, fought against termination. Tribal members sent protests to the government. Many tribal leaders went to Washington, D.C., to speak. Kickapoo Tribal Council members Vestana Cadue, Oliver Kahbeah, and Ralph Simon also testified. Their strong opposition helped the Kickapoo and other tribes avoid termination.

1960s to 1980s: Rebuilding

The tribe faced many challenges from the 1950s to the 1980s. These included high unemployment and social issues. In 1975, the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 provided government funding. The tribe also received money from the Indian Claims Commission. This allowed the Kansas Kickapoo to build homes for seniors and families. They also built a gymnasium, day care center, and senior center.

The tribe repurchased 2,400 acres of land. They used this land to start a farming and ranching business. They also built the Kickapoo Nation school for grades K–12. Most tribal members worked for tribal businesses or the local Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). However, unemployment remained high. It reached 93% between 1980 and 1982.

Gaming and Modern Success

In 1992, the tribe signed an agreement with the Governor of Kansas. This agreement was to build a casino. The state legislature initially opposed the idea. But negotiations continued. In 1995, Kansas created a State Gaming Agency. In 1996, the legislature passed the Tribal Gaming Oversight Act. This law set up a board to regulate tribal gaming. The tribes of Kansas funded this board.

On May 18, 1996, the Kickapoo Tribe opened the Golden Eagle Casino. It was the first casino in Kansas. The casino is on the Kickapoo Reservation. It created over 300 jobs in Horton, Kansas. The money from the casino has helped support the tribe's schools and health care.

Images for kids

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |