King George's Fields facts for kids

A King George's Field is a special public park or playing area in the United Kingdom. These fields were created to remember King George V, who was king from 1910 to 1936.

After King George V passed away in 1936, a group of people, led by Sir Percy Vincent, decided to create a unique memorial. They didn't just want a statue. Instead, they came up with the idea of creating playing fields all over the country.

The goal was:

To help create playing fields across the United Kingdom for everyone to use and enjoy.

Each of these playing fields would be called 'King George's Field'. They would also have special plaques or signs to show they were a memorial to the late King. These signs had to be approved by the main committee.

Local communities helped raise money to buy the land. The King George's Fields Foundation then gave extra money to help. Once bought, the land was given to the National Playing Fields Association. This group is now called Fields in Trust. Their job was to "protect and keep the land safe for public use." New fields were still being added in the 1950s and early 1960s.

When the King George's Fields Foundation stopped working in 1965, there were 471 King George's Fields. These fields are all over the UK. Today, Fields in Trust legally protects them. Local councils or groups of trustees manage them.

Special rules and agreements ensure that these open spaces will always be there for people to play and enjoy.

Contents

How King George's Fields Started

A Special Memorial Idea

When King George V died on January 30, 1936, people wanted to create a national memorial. The Lord Mayor of London started a committee to decide what kind of memorial it should be. In March 1936, they agreed on two things: a statue in London and a special project that would help people across the country. This project would be named after King George V.

So, in November of that year, the King George's Fields Foundation was officially set up. Its main goal was to create playing fields. Many people realized that as towns grew, there were fewer open spaces. This could affect how healthy young people were.

The Foundation's aim was "to help create playing fields across the United Kingdom for people to use and enjoy. Each field would be called 'King George's Field' and have special plaques or signs to remember the King."

A 'Playing Field' was defined as "any open space used for outdoor games, sports, and fun activities."

This project was flexible. It focused on towns but also included other areas. It encouraged local people to get involved and accept gifts of money or land. Each field would have a special sign to remember King George V. This was seen as something the King would have wanted. It helped young people get fresh air and exercise, which was good for them and the country.

Funding the Fields: A Helping Hand

The Foundation wanted to create a lasting memorial: playing fields named 'King George's Fields'. These fields would be bought, planned, equipped, and kept safe for fun activities in towns and villages. However, buying and setting up all these fields was very expensive. The King George's Fields Foundation couldn't do it alone.

To raise money, a national appeal was launched. Before World War II, about £557,436 was collected. The Foundation soon realized this wasn't enough to cover all the costs. So, they decided to give out 'grants-in-aid'. This meant they would give some money to local groups or councils. These local groups would then raise the rest of the money needed and promise to look after the fields.

This plan, called the Grant-in-Aid Policy, started on March 1, 1937. It needed support from many people and local governments. To make things easier, the Foundation worked with the National Playing Fields Association (NPFA). The NPFA helped review proposals and decide where grants should go.

The amount of money given depended on things like the local population, how many playing fields already existed, and the local economy. There were no strict rules about the size or facilities of a field. Some fields were very large, like one in Enfield, London, which is about 128 acres (0.52 km2). It has many pitches for different games. The smallest field is less than a quarter of an acre in the City of London, where children needed a safe place to play off the streets.

There were also rules to follow. The Foundation wanted to make sure the fields would last forever as a memorial. So, the land had to be legally protected. Money was not given for projects that might disappear after a few years. The land also had to be used for playing. Ornamental gardens or just parks were not accepted.

Also, each field needed a special entrance. This entrance would proudly display the heraldic panels that marked it as a 'King George's Field'. The Foundation encouraged simple designs using local materials, rather than fancy or expensive gates.

The Fields Grow and Change

Between March 1, 1937, and the start of World War II in September 1939, the Foundation approved 462 projects. They had received about 1,800 applications! Around £400,000 was given out as grants to towns and villages across the country. However, during the seven years of war, building new playing fields mostly stopped.

After 1945, the world had changed. Other important issues like health, education, and housing became top priorities. Many original plans for fields were dropped. But in some cases, new plans were approved and received grants. All the fields were finally finished by the 1960s.

It took a while for all the 'King George's Fields' to be fully completed. Here's a quick look at the final numbers:

| Number of Fields |

Area | Total Cost £ |

Grants Given | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| England | 344 | 3,210 acres | 3,433,876 | 458,407 |

| Scotland | 85 | 723 acres | 379,849 | 93,495 |

| Wales | 35 | 329 acres | 253,070 | 53,840 |

| Northern Ireland | 7 | 26 acres | 32,135 | 11,375 |

| Totals | 471 | 4,288 acres | 4,098,930 | 617,117 |

Notes:

- The numbers for England include the Channel Islands.

- 19 fields were paid for entirely by local groups. They still got the special plaques and were recognized as 'King George's Fields'.

- The Foundation also gave the 'King George's Field' name and plaques to places outside the UK, like Barbados, the Falkland Islands, Malta, Nigeria, and Yemen.

Here's who owned the land for these fields:

| Main local councils | Parish, town or community councils | Local trustees | NPFA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| England | 203 | 105 | 25 | 11 |

| Scotland | 71 | – | 14 | – |

| Wales | 17 | 11 | 6 | 1 |

| Northern Ireland | 5 | – | 1 | 1 |

| Totals | 296 | 116 | 46 | 13 |

Passing the Torch: Fields in Trust Takes Over

In the 1960s, more changes happened. Almost 30 years had passed since the Foundation began. It was time to hand over responsibility to the National Playing Fields Association (NPFA), which is now called Fields in Trust. Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh was the President of the NPFA for many years. His grandson, Prince William, Duke of Cambridge, took over in 2013.

The King George's Fields Foundation was never meant to last forever. So, on December 1, 1965, the NPFA officially became the main trustee for the charity. Any remaining money, about £41,251, was given to the NPFA. They also took on the job of paying out £12,200 for unfinished projects related to the King George's Fields.

Under this new agreement, the NPFA's job grew. They were now responsible for "preserving" (keeping safe) the King George's Fields, not just helping to "establish" (create) them. This means that if a local group wants to make changes to a field, they need permission from the NPFA. The NPFA's duty is to protect these fields. They also got the power to use leftover money for repairs or to replace things like the special heraldic panels.

The King George's Fields were created to honor King George V. They provided and protected valuable open spaces and facilities. These fields are still very important, especially for children and young people. Most of them are set up as charities and are protected "forever."

The Foundation's goal in 1936 was to make its money go as far as possible. The total value of the 471 'King George's Fields' was about £4,000,000. This was the cost of buying and developing the land by local groups, with help from the Foundation's grants.

The Special Entrances and Plaques

Why Entrances and Plaques Matter

Every 'King George's Field' is part of a national memorial to King George V. Because of this, the land must be legally set aside for public fun and protected forever. Another rule was that the Foundation's architect had to approve the design of the entrance. This entrance is where the special heraldic panels are displayed. The most important thing for the design was that it should be 'appropriate'. This meant simple designs that fit the area and used local materials. Local groups could choose their own architect, but the Foundation's architect offered guidance if needed.

On November 3, 1936, the King George's Fields Foundation (KGFF) became a charity. Its goal was "to help create playing fields for people to use and enjoy across the United Kingdom." All these fields had to be called 'King George's Field' and marked with special heraldic panels.

These panels were a gift from the Foundation to all approved fields. They became the official symbols of this national memorial. Even though there wasn't one specific design for the entrances, it was agreed that every field should have a unique sign linked to King George V.

Designing the Entrances

The Foundation and the National Playing Fields Association (NPFA) worked together.

- Local communities would get, plan, equip, maintain, and protect playing fields. They got help through the Grant-in-Aid Policy, which started on March 1, 1937.

- All plans for fields were first sent to the Foundation. If a field was suitable to become a 'King George's Field', it was inspected. The Foundation's final approval meant the field would get the special heraldic panels and a grant.

Today, the NPFA (now Fields in Trust) still needs to approve any plans for King George's Fields.

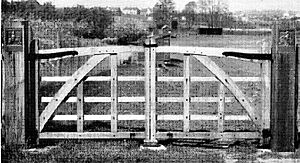

The Foundation had rules for the entrance designs because it was a national memorial. They didn't want overly fancy or expensive entrances. Many local groups created designs that met the basic rules. They made sure to use local conditions and materials in their designs.

The size and material of the entrances depended on the size of the field and the community using it. It was suggested that gates should be set back from the road. This created a safe space for children leaving the field. If a field didn't have a fence, gates weren't needed. But pillars with the heraldic panels could mark the main entry point.

The type of stone for the pillars was also important. High-quality local materials were preferred. For example, stone pillars in Bath would look different from those in Derbyshire or Cornwall. If a field had a stone wall, the wall itself might be raised to display the panels, instead of building new pillars. Brick pillars were made from narrow bricks, not machine-made ones, and fancy decorations were avoided.

For many villages, a simple wooden gate made of English oak was best. It would be hung on oak posts with hinges made by a local blacksmith. If iron gates were used, they had to be simple and made of wrought iron. They also needed to be easy for children to open and close. The gates had to be strong enough for constant use. The memorial panels were placed on the upper part of each gate pillar.

The Heraldic Panels: A Royal Symbol

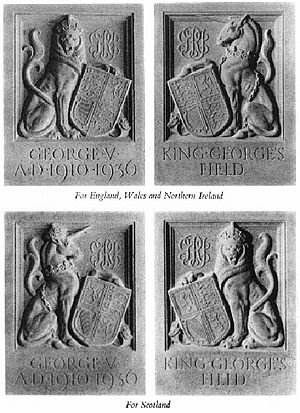

The heraldic panels were made of stone, bronze, or sometimes brass. These panels were, and still must be, displayed at the main entrance of the field. The Lion panel is usually on the left side of the entrance, and the Unicorn panel is on the right. However, in Scotland, it's the other way around!

If the entrance pillars are made of brick or stone, the panels are stone. They are about 2 feet (0.61 m) high and 1 foot 6 inches (0.46 m) wide. If wooden posts support the gate, smaller bronze plaques are used, about 11¼ inches (28.6 cm) high and 8¼ inches (21 cm) wide.

The panels were designed by George Kruger Gray. For England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, the left panel shows the Lion holding a Royal Shield. Below it are the words 'George V' and 'A.D. 1910–1936'. The right panel shows the Unicorn holding a similar shield with 'King George's Field' underneath. In Scotland, the the Lion and the Unicorn switch places. The Scottish coat of arms is on the shield, and the Unicorn wears a crown. The words below are the same.

These panels are a key part of the Foundation's history. Most fields are protected as charities forever, thanks to special legal agreements. The NPFA (Fields in Trust) provides guidance and information on the specific design of these important panels.

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |