Knap Hill facts for kids

Knap Hill is a special place in northern Wiltshire, England. It sits on the edge of the Vale of Pewsey, about 1 mile (1.6 km) north of Alton Priors village. At the top of the hill, you'll find an ancient earthwork called a causewayed enclosure.

These enclosures are from the Neolithic period, also known as the New Stone Age. They started appearing in England around 3700 BC. They are areas partly or fully surrounded by ditches that have gaps, like pathways, called causeways. We don't know for sure what they were used for. They might have been settlements, meeting places, or even special places for ceremonies. Knap Hill is now a protected ancient monument.

Knap Hill is famous because it was the first causewayed enclosure ever dug up and identified. In 1908 and 1909, archaeologists Benjamin and Maud Cunnington explored the site. Maud Cunnington wrote reports about their findings. She noticed the many gaps in the ditch and bank around the enclosure.

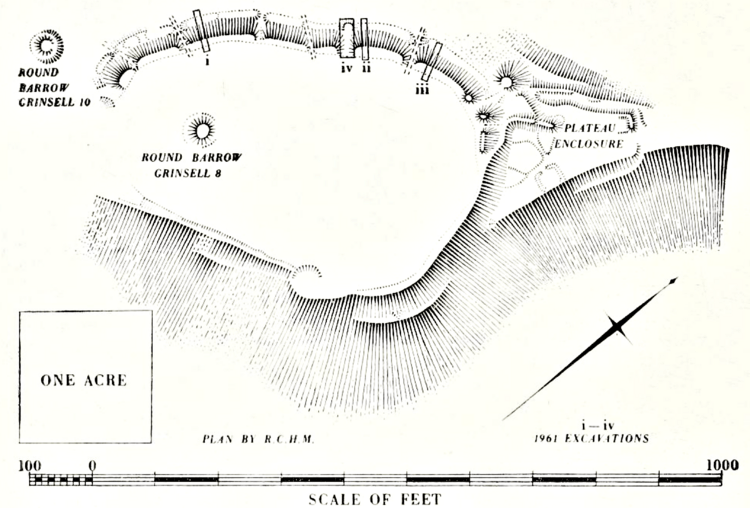

Later, in the 1920s, after other sites like Windmill Hill were explored, people realized that causewayed enclosures were a key type of monument from the Neolithic period. Today, about a thousand causewayed enclosures have been found in Europe, with around seventy in Britain. Knap Hill was dug up again in 1961 by Graham Connah. He carefully recorded everything he found.

In 2011, a project called "Gathering Time" used radiocarbon dating to figure out the age of the enclosure. They looked at new dates from Connah's finds. They found a 91% chance that Knap Hill was built between 3530 and 3375 BC.

Inside the Neolithic enclosure, there were two burial mounds (called barrows). At least one more barrow was outside it. The hilltop also has remains of a Romano-British settlement. This settlement was on a smaller area next to it, called the plateau enclosure. People also lived here in the 1600s. An Anglo-Saxon sword was found in the smaller enclosure. There's also proof of a big fire in the same area. This suggests the Romano-British settlement on the hilltop ended suddenly, perhaps due to conflict.

Contents

What is a Causewayed Enclosure?

The main archaeological site at Knap Hill is a causewayed enclosure. This type of earthwork first appeared in England during the early Neolithic period, around 3700 BC. Both the enclosure and the hill itself are known as Knap Hill.

Causewayed enclosures are areas that are partly or fully surrounded by ditches. These ditches have gaps, or "causeways," of untouched ground. They often also have earth banks and wooden fences (palisades). For a long time, experts have debated what these enclosures were used for.

They used to be called "causewayed camps" because people thought they were settlements. Early researchers even thought people lived in the ditches! But this idea was later changed. Most now believe any settlement would have been inside the enclosure.

In 1912, a report on Knap Hill suggested the banks were for defense. But the causeways were hard to explain if it was a military fort. Some thought they might be "sally ports" for defenders to rush out and attack. Evidence of attacks at some sites supported the idea that they were fortified settlements.

These enclosures might have been places for seasonal meetings. People could have traded cattle or other goods like pottery there. If they were important gathering spots, they might show that local groups had leaders. There is also evidence they were used for funeral ceremonies. Things like food, pottery, and even human remains were carefully placed in the ditches.

Building these enclosures took a lot of effort and organization. People had to clear land, prepare wood for fences, and dig ditches. This suggests that communities worked together on these big projects.

Discovering More Enclosures

In 1930, archaeologist Cecil Curwen found sixteen sites that were likely Neolithic causewayed enclosures. Digs at five of these had already confirmed they were from the Neolithic period. Four more of Curwen's sites are now also known to be Neolithic.

More enclosures were found over the years. The number of known sites grew a lot when people started using aerial photography in the 1960s and early 1970s. Earlier sites were mostly found on chalk uplands, which are high, chalky hills. But many of the ones found from the air were on lower ground.

Over seventy causewayed enclosures are known in Britain and Ireland. They are one of the most common types of early Neolithic sites in western Europe. About a thousand are known in total. They appeared at different times across Europe. For example, they were built before 4000 BC in northern France. But they appeared later, just before 3000 BC, in northern Germany, Denmark, and Poland.

In southern Britain and Ireland, these enclosures started to appear just before 3700 BC. People continued to build them for at least 200 years. Some enclosures that were built early on were still used as late as 3300 to 3200 BC.

Exploring the Knap Hill Site

Knap Hill is in Wiltshire, about 1 mile (1.6 km) north of the village of Alton Priors. It is part of the chalk hills that form the northern edge of the Vale of Pewsey. Golden Ball Hill is to its east, and Walker Hill is to its west.

Golden Ball Hill shows signs of Mesolithic activity, which is an even older Stone Age period. Two other Neolithic sites are nearby. These are Adam's Grave, a long burial mound on Walker Hill, and Rybury, another causewayed enclosure, about two miles (3.2 km) further west.

The south side of Knap Hill is the steepest. The slopes to the north and west are more gentle. A narrow strip of land connects it to Golden Ball Hill on the east. There used to be two round burial mounds inside the enclosure. One of these was destroyed in the 1800s by people digging for flint. A third mound is just outside the enclosure, to the southwest. There might have been a fourth mound to the south, but records are unclear.

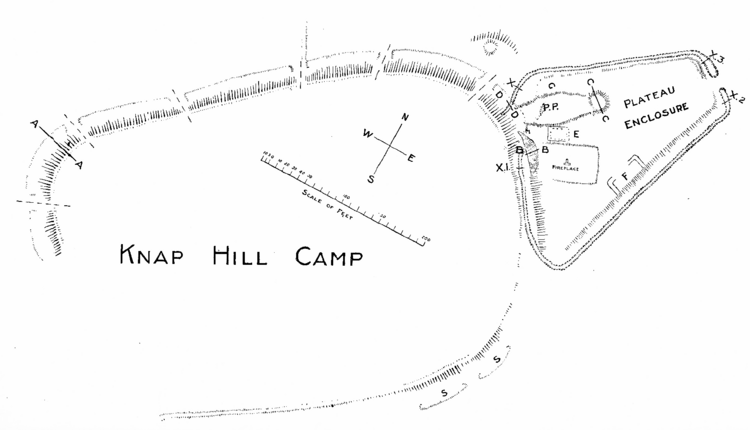

The Neolithic causewayed enclosure at the top of Knap Hill has a ditch and a bank inside it. They run along the northwestern edge of the hilltop and partway down the southwestern and northeastern sides. Both the ditch and the bank were built in seven sections, with six gaps, or causeways, between them.

Another short ditch at the eastern corner of the hill was divided into two parts. But no ditch or bank has been found along the southern edge of the hilltop yet. Knap Hill is unusual because the gaps in the ditch match the gaps in the bank exactly. At most sites, there are many more gaps in the ditch than in the bank. The enclosure covers an area of about 2.4 hectares (5.9 acres).

To the northeast of the main enclosure is a smaller archaeological site. It's called the plateau enclosure. This site dates from before and during the Roman-British period. The plateau enclosure was also used in the 1600s, perhaps by shepherds.

A bank with a ditch on either side runs down the hill from the southeastern corner of the causewayed enclosure. This area is too steep for it to have been a pathway. Similarly, from one of the causeways on the northwestern edge, a bank runs down the hill. This one has only one parallel ditch. Both of these were likely boundary markers.

Knap Hill is an example of an "upland-oriented" enclosure. It's on a noticeable hill, which looks dramatic from the south. But the land where the enclosure is built slopes towards the higher ground to the north. Several other upland enclosures are set up this way, and it's probably not by chance.

Whitesheet Hill, Combe Hill, and Rybury are other examples. These enclosures are hard to see from the lower ground below them. But they are much more visible when viewed from nearby higher lands. The archaeologist Roger Mercer called Knap Hill "the most striking of all causewayed enclosures." He suggested viewing it from the road to the west that goes from Marlborough to Alton Priors. The site is protected as an ancient monument.

Early Investigations

Knap Hill was first mentioned by people interested in old things in 1680. John Aubrey described it as "a small Roman camp above Alton." Richard Colt Hoare also mentioned Knap Hill in the early 1800s. He noted "two small barrows, and another on the outside."

John Thurnam's Work (1850s)

John Thurnam looked into the burial mounds between 1853 and 1857. He found that the easternmost of the two mounds inside the enclosure had been destroyed. Flint diggers had removed all traces of it. The western mound was about two feet (60 cm) high, with a small ditch around it.

Near the top of this mound, Thurnam found animal bones. He said they were "of a sheep and perhaps other ruminants." He noted this was common in other Wiltshire mounds, which often had animal bones near the surface. He thought they might be from a sacrifice or a feast over the graves. Under the middle of the mound, there was a circular hole dug into the chalk. It was two feet (60 cm) deep and two feet (60 cm) across. It was almost full of ashes and burnt bones.

The mound outside the enclosure, to the southwest, was about a foot (30 cm) high. Thurnam found nothing there but some animal bones near the surface.

The Cunningtons' Discoveries (1908–1909)

The Neolithic enclosure was first dug up by Maud and Benjamin Cunnington. This happened during the summers of 1908 and 1909. Their first summer's work showed that the earthworks were made of segments. This led Maud Cunnington to write a short note in the journal Man in 1909. She asked readers for ideas to explain what they found:

Recent excavations [at] Knap Hill Camp in Wiltshire revealed a feature which, if intentional, appears to be a method of defence hitherto unobserved in prehistoric fortifications in Britain... There are six openings or gaps through the rampart. It was thought at first that ... some of these gaps were due to cattle tracks, or possibly had been made for agricultural purposes... Excavations clearly showed that none of these gaps in the rampart are the result of wear or of any accidental circumstance, but that they are actually part of the original construction of the camp... Outside of, and corresponding to, each gap the ditch was never dug; that is to say, a solid gangway or causeway of unexcavated ground has been left in each case... Given the need for an entrenchment at all, it seems at first sight inexplicable why these frequent openings should have been left, when apparently they so weaken the whole construction... It has been suggested ... that the work of fortifications was never finished, [but there is] considerable evidence in favour of these causeways being an intentional feature of the original design of the camp... The possible use which the gangways may have served is put forward with all diffidence, and any suggestion on the subject would be welcomed.

This was the first time that causewayed ditches had been clearly identified. By the end of their second summer, they had dug enough to prove that the ditches really did end where they seemed to from above ground.

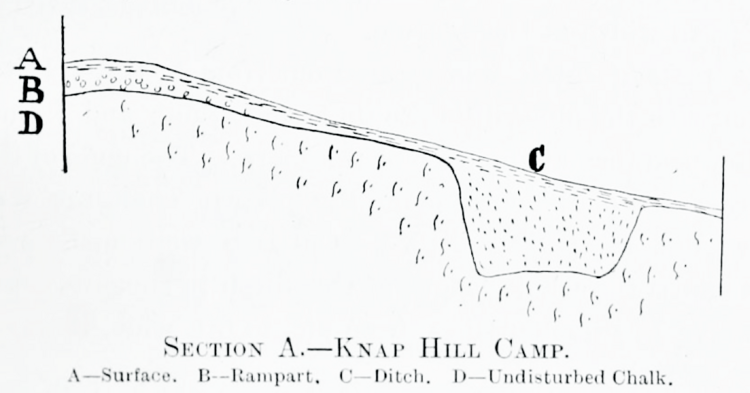

Maud Cunnington wrote a detailed paper in 1912. She and Benjamin dug a 54 feet (16 m) long part of one of the ditches. They found that its width and depth changed a lot. It was seven feet (2.1 m) deep and ten feet (3.0 m) wide at the bottom at one end. But it was eight feet (2.4 m) deep and only eighteen inches (0.46 m) wide at the bottom at the other end. They also dug along the southern edge of the hilltop. They wanted to see if a ditch existed there that was no longer visible. They found two short ditch sections at the eastern corner (marked S–S on the map).

Most of the items found in the ditches were in groups. They were usually within a foot (30 cm) of the bottom. These items included pieces of pottery, flint flakes, burnt flints, animal bone fragments, and pieces of sarsen stone. The only human bone found was a small jaw bone with worn teeth.

The pottery was rough and had flint pieces mixed in. It was found with flint flakes. This made Maud Cunnington think the people who used the pottery might have been Neolithic. However, she noted that it was hard to tell undecorated pottery from the Bronze Age and Neolithic periods apart. So, she couldn't say for sure which period it was from. The Cunningtons found several places where flint tools were made. One group had seventy-two flint chips six feet (1.8 m) deep in the ditch.

The Cunningtons also found a second enclosure to the northeast of their main dig site. This made their work more complicated. To tell it apart from the "Old Camp," they called the new one the "Plateau Enclosure." Maud Cunnington realized the plateau enclosure was much newer than the old one. Its southwestern ditch was dug through the old enclosure's ditch, which had almost completely filled with dirt by then. Cunnington thought the plateau enclosure was built no earlier than the early Iron Age.

The ditch and low bank around the plateau enclosure were mostly hidden on the surface. The Cunningtons dug sections around its edge to confirm its path. A gap was also found in the plateau enclosure ditch where it met the old enclosure. But Cunnington couldn't figure out its purpose. An entrance seemed unlikely because the bank was very steep there.

The pottery found in the plateau ditch and bank was much better quality than the rough Neolithic pottery from the old enclosure. It included bead-rim pottery. Cunnington dated this pottery to just before, or during the early years of, the Roman occupation.

Inside the plateau enclosure was a long bank, running from southwest to northeast. It had a round mound at its northeastern end. The Cunningtons found pottery pieces in the long bank that Maud Cunnington dated to Roman times. They also found two pits (marked P. on the map) under the center of the bank. These pits were dug before the bank was built. Both were circular, about two feet (60 cm) deep, and 3.5 to 4 ft (1.1–1.2 m) wide. They contained flint flakes, rough pottery, and some animal bones. Cunnington thought they were from the same time as the old enclosure. She believed it was just a coincidence that the long bank was built over them.

A 6th-century Anglo-Saxon iron sword was found near the edge of the long mound (at G on the map). A round fire pit was found under the circular mound. It contained wood ash and pottery, some of which Cunnington identified as Roman. Another fireplace was found to the southeast of the long mound. This was in a rectangular raised area (which Cunnington called the dais). This fireplace was T-shaped. It held the bottom stone of a quern (a hand mill for grinding grain), which was damaged by heat. It also had four iron nails and several pottery pieces. Cunnington suggested that the fireplace couldn't have been used with the quern in it. This, along with the sword and signs of intense heat, suggested a sudden and possibly violent end to the people living in the enclosure.

Between the long bank and the dais were the remains of a small building (marked E on the map). It was 23 by 13.5 ft (7.0 by 4.1 m) and had walls made of chalk blocks. Postholes were found in the walls. A pile of rubbish next to the building contained a piece of 17th-century pottery. In the area of the building and the dais, many clay pipes were found. Some of these pipes had makers' stamps, so they could be dated accurately. The pipes and pottery from this area were both from the 17th century. They were mixed with Roman pottery in the dais. This led Cunnington to think that the dais had been farmed by the 17th-century people living on the hilltop. This farming would have mixed the soil and the pottery from different time periods.

The ruins of another rectangular building (F on the map) were found against the eastern side of the plateau enclosure's bank. Both Roman and 17th-century pottery pieces were found in its walls and under its foundations. It was clear the building was built after the plateau enclosure. But the Cunningtons found no other clues to help date it.

The Cunningtons also opened the burial mound outside the old enclosure, to the southwest. They found a skeleton fairly close to the surface, lying face down. It was missing all the leg and foot bones, and the right hand. Maud Cunnington thought the body was buried so close to the surface that animals might have disturbed the missing bones. The only pottery pieces found were from the Roman period and were all near the surface. This suggests the burial happened before the Roman occupation.

Two low banks were found running down the hill. One was from the two ditches marked S on the map. The other was on the opposite side of the enclosure, leading down from one of the causeways on the northwestern edge. The one to the east was known locally as "The Devil's Trackway." The northwestern bank ran for fifty yards (46 m) towards an old path across the hill.

C. W. Phillips's Dig (1939)

In 1939, C. W. Phillips dug up a bowl barrow outside the enclosure. However, he never published a report about it. Two barrows outside the enclosure are listed in a guide to Wiltshire by Leslie Grinsell, published in 1957. They are called Alton 10 and Alton 13. Phillips dug up Alton 13. It's possible that these two barrows are actually the same one. If so, the barrow Phillips dug was the same one Thurnam explored in the 1850s.

Phillips found a crouched burial at the old ground surface, along with Neolithic pottery pieces. These pottery pieces might not mean the barrow is from the Neolithic period. They could have been on the site when the barrow was built. Grinsell says Phillips noted the barrow was south of the causewayed enclosure. If this is correct, it's not the same barrow Thurnam opened.

Graham Connah's Excavation (1961)

In 1961, Graham Connah dug up the causewayed enclosure again. He cut three trenches (i to iii on the diagram) across different parts of the ditches and banks. He also fully dug up one causeway (iv on the diagram), including both ends of the two ditches next to it. Like the Cunningtons, Connah found a group of flint-making tools at the chalk surface in one of his digs.

Connah found only a few pieces of pottery. So, he combined his finds with those from the earlier excavation for analysis. However, some records about where the earlier finds came from had been lost since 1912. Most of the pottery pieces found in 1961 had flint pieces mixed in. But four pieces, from a single pot, had shell pieces mixed in. This means they must have come from at least 20 miles (32 km) away. Similar mixes of finds had been reported at Windmill Hill, Robin Hood's Ball, and Whitesheet Hill.

Connah classified the pottery from the ditches as Windmill Hill ware. This was a common way to classify pottery in the 1960s. It tried to identify different cultures within the Neolithic period. But this classification has since changed. Now, Neolithic sites are generally separated into Early and Late Neolithic.

Besides the Windmill Hill ware, fragments from seven or eight pots of Beaker ware were found. Connah thought these might have come from short visits to the hilltop, rather than people living there. Connah also found some Romano-British pottery in his digs. This included four Samian pottery pieces. One of these could be dated to the late 1st century AD. Some later medieval pottery fragments were found in the upper layers of the digs. All of these might have originally been part of a single pot. These pieces could not be accurately dated.

In one of the digs, a woman's skeleton was found near the top of the ditch. Nails found around her feet were thought to be the remains of boots that had been reinforced with them. Connah believed the skeleton probably dated to the Roman-British period. He thought the Neolithic ditch was simply a convenient soft spot for burial. The woman was likely in her 40s when she died and was about 5 feet 2 inches (1.57 m) tall. She had osteoarthritis and jaw infections. An evaluation by the Duckworth Laboratory in Cambridge said she "most probably suffered agonies."

Connah found ditches on both sides of the bank leading down from the eastern corner of the causewayed enclosure. His dig of one of the causeways (marked "iv" on his map) found a shallow ditch cut into the chalk. This ditch followed the line of the bank leading down the hill on that side. It lay beneath another ditch along one side of that bank. The Cunningtons had not noticed any of these ditches. Connah concluded that both were likely built to mark boundaries.

The Gathering Time Project (2011)

In 2011, the Gathering Time project shared the results of a study. They re-analyzed the radiocarbon dates of nearly 40 causewayed enclosures. They used a method called Bayesian analysis. Knap Hill was one of the sites included in this project.

Connah had obtained two radiocarbon dates from samples collected during his 1961 excavation. He published these results in 1969. These results were included in the Gathering Time analysis. One of the samples was even re-tested. Five other samples from Connah's finds were also radiocarbon dated. This was possible because Connah's records were very precise. They could identify samples that were clearly linked to the building of the enclosure.

The study concluded that there was a 91% chance that Knap Hill was built between 3530 and 3375 BC. There was also a 92% chance that the ditch had filled up with dirt sometime between 3525 and 3220 BC. The researchers thought it was likely that the site was used for "a short duration." This probably meant "well under a century, and perhaps only a generation or two."

Images for kids

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |