Krste Misirkov facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Krste Petkov Misirkov

|

|

|---|---|

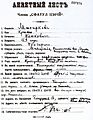

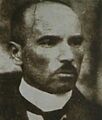

Portrait of Krste P. Misirkov

|

|

| Born | Krste Petkov Misirkov 18 November 1874 Postol, Salonica Vilayet, Ottoman Empire (now Pella, Greece) |

| Died | 26 July 1926 (aged 51) Sofia, Kingdom of Bulgaria |

| Pen name | "K. Pelski", "Sekol" |

| Occupation | philologist, teacher, historian, ethnographer, translator and professor. |

| Citizenship | Ottoman, Moldavian, Russian, Bulgarian |

| Education | Doctor's degree of philology and history |

| Alma mater | Faculty of philology and history at the University of Petrograd |

| Genre | history, linguistics, philology, politics, ethnography and analytic. |

| Subject | history, language and ethnicity |

| Literary movement | Macedonian scientific-literary association "St. Clement" |

| Notable works | "On Macedonian Matters", the magazine "Vardar", over 30 articles published in different Russian and Bulgarian newspapers. |

| Spouse | Ekaterina Mihaylovna - Misirkova |

| Children | Sergey Misirkov |

| Signature | |

|

|

Krste Petkov Misirkov (18 November 1874 – 26 July 1926) was an important person from the Macedonia region. He was a philologist (someone who studies language), a journalist, a historian, and an ethnographer (someone who studies cultures).

Between 1903 and 1905, Misirkov published a book and a magazine. In these works, he said that Macedonian people had their own unique identity. This identity was separate from other groups in the Balkans. He also tried to create a standard Macedonian language. This language was based on the dialects spoken in central Western Macedonia.

In North Macedonia, many people see Misirkov as a very important figure. Some even call him "the founder of the modern Macedonian literary language." This is because of his work to create a standard Macedonian language.

However, Misirkov also had other views. He helped start a group in 1900 that supported Bulgaria. Later, he wrote articles that showed a Bulgarian nationalist viewpoint. During the Balkan Wars, he supported the idea of a "Greater Bulgaria." His views changed several times throughout his life. Sometimes he supported a Macedonian identity, and other times a Bulgarian one.

Because his views changed, people in Bulgaria and North Macedonia have different ideas about his legacy. Scholars have tried to understand his different statements. They say he saw himself and the Slavs of Macedonia as Bulgarians in a larger sense. But within that larger group, he also wanted Macedonians to have their own culture and identity.

Contents

Misirkov's Life Story

Early Life and Education

Krste Petkov Misirkov was born on November 18, 1874. His birthplace was the village of Postol in the Ottoman Empire. This area is now part of Greece. He started school in a local Greek school.

He had to leave school because his family did not have enough money. At that time, the Serbian government offered scholarships to young people. They wanted to encourage pro-Serbian ideas. Misirkov received one of these scholarships.

Studying in Serbia and Bulgaria

Misirkov soon realized that the Serbian scholarship aimed to promote Serbian ideas. He and other Macedonian students protested against this. As a result, Misirkov moved to Sofia, Bulgaria.

In Bulgaria, he faced a similar situation. There, he found pro-Bulgarian ideas being promoted. Misirkov tried to go back to Serbia for school, but he was rejected. He had to enroll in a special school for teachers. This school also had its own political goals.

Another student protest happened, and the school closed. Misirkov was sent to Šabac, where he finished his secondary education. He later graduated from another teacher's school in Belgrade in 1895. In 1893, he started a student group called "Vardar."

Time in the Russian Empire

Misirkov's qualifications from Belgrade were not accepted in Russia. So, he had to start his studies again. In 1897, he entered the Saint Petersburg Imperial University. He joined the Bulgarian Students Association there.

He also became part of the Secret Macedonian-Adrianople Circle. Misirkov gave his first scholarly lecture here. It was about the history of the Balkans to the Russian Geographical Society.

In November 1900, Misirkov and other students formed a group in Saint Petersburg. Their main goal was for Macedonia and Thrace to become self-governing. They wanted this to be guaranteed by the powerful countries of the world. At this time, Misirkov saw the Slavic people of Macedonia and Thrace as Bulgarians.

Return to Ottoman Macedonia

Misirkov faced money problems for his studies. He accepted a teaching job in Bitola from the Bulgarian Exarchate. There, he became friends with the Russian consul. He planned to open schools and publish textbooks in Macedonian.

However, the Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising in 1903 changed his plans. The Russian Consul was also killed. Misirkov soon returned to Russia. In Russia, he wrote articles about the uprising.

He then wrote his famous book, "On the Macedonian Matters." He published it in Sofia. This book was written in a Central Macedonian dialect. In it, Misirkov criticized the Bulgarian Exarchate and the uprising. He saw them as being too Bulgarian. Because of this, some people tried to destroy copies of his book.

Back in Russia

In 1905, Misirkov moved to Berdiansk in Southern Russia. He started publishing his journal "Vardar" again. He also got a job as a teacher. After 1905, Misirkov often wrote articles that supported Bulgarian views. Some believe this was because he received threats.

He worked with a Sofia magazine called "Macedonian-Adrianople Review." In 1909, he wrote about South Slavic epic legends. He also wrote an article about improving relations between Serbians and Bulgarians. In 1910, he was invited to a Slavic Festival in Sofia as a special guest.

When the First Balkan War began, Misirkov went to Macedonia. He was a Russian war reporter. He wrote articles asking for the Ottomans to leave Macedonia. After the Second Balkan War in 1913, Misirkov went back to Russia. He taught Bulgarian in schools in Odessa and later in Chișinău.

While teaching, Misirkov wrote to professors at Sofia University. He asked for a job there. He said he wanted to return to Bulgaria as a Bulgarian. He wanted to research the history of Bulgarian lands, especially Macedonia.

He also connected with the Macedonian Scientific and Literary Society. This group published a journal called "Makedonski glas" (The Voice of Macedonia). Misirkov wrote for this magazine using the name "K. Pelski." In "The Voice of Macedonia," he wrote about Macedonian ideas. He said these ideas were different from Bulgarian ones.

During World War I, Bessarabia became a republic. Misirkov was chosen to be a member of its local parliament. He represented the Bulgarian minority there. In 1918, Bessarabia joined Romania. Misirkov tried to get textbooks from Bulgaria. When he returned, he was arrested by Romanian authorities and sent to Bulgaria.

Final Years in Bulgaria

After being sent out of Romania, Misirkov returned to Sofia in late 1918. He worked at the National Museum of Ethnography for a year. Later, he taught and directed high schools in Karlovo and Koprivshtitsa.

He continued to write articles about the "Macedonian Question." This refers to the debate about the identity and future of Macedonia. Krste Misirkov died in 1926. He was buried in Sofia. The Ministry of Education helped pay for his burial. They honored him as a respected Bulgarian educator.

Misirkov's Important Works

Misirkov wrote one book and a diary. He also published one issue of a magazine and over thirty articles. His book, magazine, and some articles were written in Central Macedonian dialects. These dialects form the basis of the modern Macedonian language.

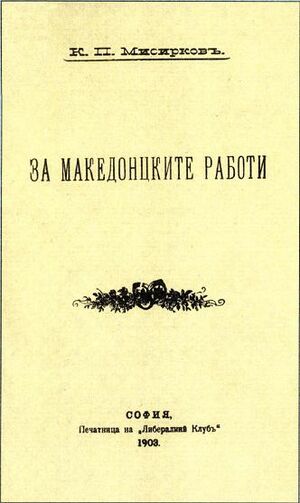

"On the Macedonian Matters"

One of Misirkov's most important works is his book On the Macedonian Matters. It was published in Sofia in 1903. In this book, he set out the main ideas for modern Macedonian identity.

The book was written in Macedonian dialects from the Prilep and Bitola areas. It argued that Macedonians should have their own separate nation. It also called for a unique Macedonian language to be standardized. Misirkov criticized groups that he felt were pushing Bulgarian interests in Macedonia. He believed the Macedonian literary language should come from the central Macedonian dialects.

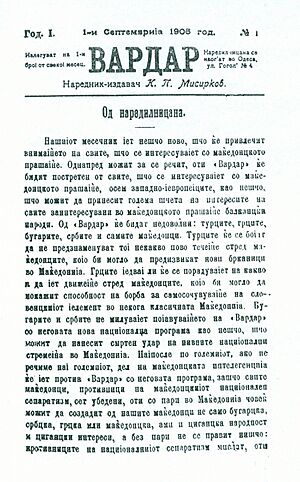

"Vardar" Magazine

Besides his book, Misirkov also created the first scientific magazine in Macedonian. This magazine was called "Vardar". It was published in 1905 in Odessa, Russia. Only one issue was printed because Misirkov had money problems.

"Vardar" was written in Macedonian. Its spelling was very similar to the spelling of standard Macedonian today. The magazine aimed to cover different scientific topics related to Macedonia.

Articles and Diary

Misirkov published many articles in various newspapers and magazines. These articles covered topics like Macedonian culture, politics, and the Bulgarian nation. He wrote them in Macedonian, Russian, and Bulgarian. Most articles were signed with his real name, but some used his pen name, K. Pelski.

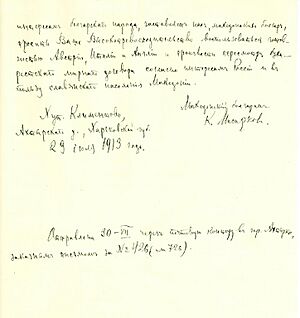

In 2006, a handwritten diary by Misirkov was found. He wrote it in Russia in 1913. Experts from Bulgaria and Macedonia confirmed it was real. The diary shows that at that time, Misirkov was a Bulgarian nationalist. It has led to new discussions about his views on Bulgarian and Macedonian identity. The diary has 381 pages and is written in Russian.

Images for kids

See also

- History of the Macedonian language

- Institute for Macedonian language "Krste Misirkov"

- Macedonian nationalism

- Macedonian studies

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |