History of the Macedonian language facts for kids

The history of the Macedonian language tells the story of how the Macedonian language developed over time. Today, it's an Eastern South Slavic language spoken in North Macedonia. This language grew from Old Church Slavonic, which was a common language used by Slavic people long ago.

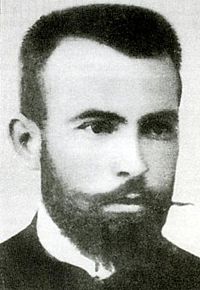

In 1903, a very important person named Krste Petkov Misirkov suggested that a standard Macedonian language should be created. He wrote about this idea in his book Za makedonckite raboti (On Macedonian Matters). Later, on August 2, 1944, Standard Macedonian was officially declared an official language by the Anti-Fascist Assembly for the National Liberation of Macedonia (ASNOM). The rules for the language were then set down the following year.

Experts who study Macedonian history say the language went through nine main stages. Blaže Koneski, another important scholar, divided its history into two big parts: an old period (from the 12th to 15th centuries) and a modern period (after the 15th century). The Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts (MANU) also notes that the language used two different writing systems: Glagolitic and Cyrillic.

Contents

How the Language Changed Over Time

Early Times

For many centuries, Slavic people living in the Balkans spoke their own local ways of talking, called dialects. They also used other dialects or languages to talk with people from different areas. The earliest period of Macedonian language development began around the 9th century and lasted until the early 11th century. During this time, religious texts from Greek were translated into Old Church Slavonic. This was based on a dialect spoken in Thessaloniki.

A special version of Old Church Slavonic, called the Macedonian recension, also appeared around this time. It was used in the First Bulgarian Empire and was linked to the Ohrid Literary School in Ohrid, which is in modern-day North Macedonia.

Around the 11th century, the common Slavic language started to break apart. This led to the rise of different Macedonian dialects. Between the 11th and 13th centuries, the Macedonian version of Church Slavonic grew. During this time, people not only translated religious texts but also wrote new ones, like praises and sermons by saints such as Saint Clement of Ohrid. These texts had unique language features, so this version is sometimes called Old Macedonian Church Slavonic.

This period, which included the start of the Ottoman rule, saw many changes in grammar and language. These changes made Macedonian part of a group of languages in the Balkans that share similar features. By the 13th century, Macedonian dialects became more distinct, showing both Slavic and Balkan characteristics. This is when many of the dialects we know today began to form.

During the five centuries of Ottoman rule in Macedonia, many words from Turkish entered the Macedonian language. These Turkish words often came from Arabic or Persian. While the written language didn't change much under Ottoman rule, the spoken dialects continued to grow further apart. We have very few surviving texts written in Macedonian from the 16th and 17th centuries.

The first printed book that included Macedonian language examples was a "conversational manual" published in 1793. It had texts written by a priest in the dialect of the Ohrid region. In the Ottoman Empire, religion was very important for telling groups apart. Muslims were the rulers, and non-Muslims were the lower classes. From the 14th to 18th centuries, a Serbian version of Church Slavonic was common in the area. But starting in the 16th century, everyday language began to appear in church writings.

Some of the earliest records of Macedonian dialects, described as Bulgarian, are found in a 16th-century dictionary written in the Greek alphabet. Early texts from Macedonia, like the four-language dictionary by Daniel Moscopolites and works by Kiril Peichinovich and Yoakim Karchovski, also saw Macedonian dialects as part of the Bulgarian language. These works, written in or influenced by local Slavic speech, appeared in the 18th and early 19th centuries. Their authors called their language Bulgarian.

The oldest texts showing specific Macedonian sounds are Old Church Slavonic texts written in Glagolitic from the 10th to 11th centuries. By the 12th century, the Church Slavonic Cyrillic alphabet became the main one. Texts that show everyday Macedonian language features started appearing in the second half of the 16th century.

Modern Times

The late 18th century marked the beginning of modern literary Macedonian. During this time, Macedonian dialects started to be used for religious and teaching works. However, writers often called the language they used "Bulgarian." Writers like Joakim Krchovski and Kiril Pejchinovik chose to write in their local dialects. They wanted their first printed books to be easy for people to understand. In the southern part of the Macedonian dialect area, the Greek alphabet was used.

The first half of the 19th century saw a rise in national feelings among South Slavs under the Ottoman Empire. Bulgarian and Macedonian Slavs wanted to create their own Church and schools. These would use a common modern Macedono-Bulgarian literary standard. At first, each group in the Macedonian-Bulgarian language area wrote in its own local dialect.

Between 1840 and 1870, there was a debate about which dialect should be the base for the new language. Two main literary centers appeared: one in northeastern Bulgaria and one in southwestern North Macedonia. These centers had different ideas because western Macedonian and eastern Bulgarian dialects were quite different. During this time, Macedonian thinkers suggested creating a Bulgarian literary language based on Macedonian dialects.

By the early 1870s, the Ottoman authorities recognized an independent Bulgarian Orthodox Church and a separate Bulgarian ethnic group. The Bulgarian Movement rejected ideas for a common language, calling Macedonian a "degenerate dialect." They said Macedonian Slavs should learn standard Bulgarian. This period also saw the rise of "Macedonists." They argued that Macedonian should be used for Macedonian Slavs, whom they saw as a distinct people. Poetry written in the Struga dialect with some Russian influences also appeared. Textbooks were published using either spoken dialect forms or a mix of Bulgarian and Macedonian.

New Beginnings

In 1875, Gjorgji Pulevski published a book in Belgrade called Dictionary of Three Languages. It was a phrasebook in Macedonian, Albanian, and Turkish, all written in Cyrillic. Pulevski wrote in his native eastern Tarnovo dialect. His work was an early attempt to create a Macedonian language standard that went beyond just one dialect. This was the first time pro-Macedonian ideas were clearly expressed in print.

Between 1892 and 1894, a magazine called Loza, run by IMRO revolutionaries, used a special writing style. They changed some letters and took inspiration from Serbian grammar.

Krste Petkov Misirkov's book Za makedonckite raboti (On Macedonian Matters), published in 1903, was the first real attempt to create a separate literary language. In his book, Misirkov suggested a Macedonian grammar. He wanted the language to be standardized and used in schools. He proposed that the Prilep-Bitola dialect should be the basis for the standard Macedonian language. However, his idea wasn't fully adopted until the 1940s. His book faced strong opposition, and many early copies were destroyed.

Before standard languages like Macedonian were formally created, the lines between South Slavic languages were not clear. The rules for these languages were still being developed. So, the creation of distinct boundaries between South Slavic languages is fairly recent. Even in 1822, experts in Europe were still debating the difference between Bulgarian and Serbian.

After the First Balkan War and between the two World Wars, linguists outside the Balkans published studies. They showed that Macedonian was a language distinct from Serbo-Croatian and Bulgarian. In the period between the wars, the area of today's North Macedonia became part of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. The local language was influenced by Serbo-Croatian. In 1934, the Comintern (a global communist organization) supported the creation of a separate Macedonian language. During the World Wars, Bulgaria briefly took control of Macedonia twice. They tried to bring Macedonian dialects back under Bulgarian language influence.

Making it Official

On August 2, 1944, at the first meeting of the Anti-fascist Assembly for the National Liberation of Macedonia (ASNOM), the Macedonian language was declared an official language. This made Macedonian the last of the major Slavic languages to get a standard written form. It was one of the three official languages of Yugoslavia from 1945 to 1991.

The first official Macedonian grammar book was written by Krume Kepeski in 1946. Blaže Koneski was one of the most important people in making the Macedonian literary language standard. Most of the standardization of Standard Macedonian happened between 1945 and 1950. Some linguists at the time said that during its standardization, Macedonian was made more like Serbian, especially in its spelling.

The standardization of Macedonian created a second standard language within a group of dialects that includes Macedonian, Bulgarian, and Torlakian dialects. This was a result of earlier language developments from the Preslav Literary School and Ohrid Literary School. Some researchers believe that Macedonian was standardized to be different from Serbian and Bulgarian. However, the dialects chosen for the standard language had not been covered by an existing standard before. So, the creation of Macedonian wasn't exactly a separation from an existing language.

Some argue that the standardization was purposely done using the dialect most unlike Standard Bulgarian (the Prilep-Bitola dialect). Others say this view doesn't consider that a common Macedonian language was already forming. The policy is thought to come from Misirkov's ideas. He suggested that Standard Macedonian should be based on dialects "most distinct from the standards of the other Slavonic languages."

After the Tito–Stalin split in 1948, some Macedonian thinkers in Bucharest created a different alphabet, grammar, and primer. These were closer to Bulgarian and were meant to be "purified" of Serbo-Croatian words found in the "language of Skopje." This was an anti-Yugoslav effort.

This attempt at standardization didn't become widely accepted. However, printed materials for refugees from Aegean Macedonia in Eastern Europe continued to be written in this different language form until 1977.

How the Macedonian Alphabet Developed

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Macedonian writers used their own Macedonian dialects. They wrote using Bulgarian and Serbian Cyrillic scripts. In South Macedonia, the Greek alphabet was also widely used by writers who went to Greek schools. Between the two World Wars, writers used alphabets from surrounding countries, including the Albanian one. The typewriters available also influenced which alphabet was used.

The official Macedonian alphabet was formally created on May 5, 1945. This was done by the leaders of the Anti-fascist Assembly for the National Liberation of Macedonia (ASNOM), led by Blaže Koneski.

Different Views on the Language

Recognition

Politicians and scholars from North Macedonia, Bulgaria, and Greece have different ideas about whether the Macedonian language exists and how unique it is. Throughout history, especially before it was standardized, Macedonian was sometimes called a version of Bulgarian, Serbian, or its own distinct language.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Greeks claimed that Macedonian dialects were a "corrupted version of ancient Macedonian." After its standardization, the use of the language has been a topic of debate in Serbia, Bulgaria, and Greece.

Between the World Wars, Macedonian was seen as a South Serbian dialect in Yugoslavia. But the government allowed it to be used in dialect literature. In the 1940s, Bulgaria had changing views on the Macedonian language. It was recognized in 1946-47 and allowed in schools in Pirin Macedonia. However, after 1948, its recognition was withdrawn, and its use was limited.

Until 1999, Macedonian was not recognized as a minority language in Greece. Attempts to introduce Macedonian-language books in schools failed. For example, a Macedonian primer called Abecedar was published in 1925 in Athens. But it was never used, and most copies were destroyed.

Professor Christina Kramer says that Greek policies have tried to deny any link between the standard Macedonian language and the Slavic-speaking minority in Greece. She sees this as an effort to "eliminate Macedonian." It's hard to know how many Macedonian speakers there are in Greece. This is because some Slavic-speaking Greeks are also considered Bulgarian speakers by Bulgarian linguists. In recent years, there have been attempts to get the language recognized as a minority language in Greece. In Albania, Macedonian was recognized after 1946. Mother-tongue instruction was offered in some village schools up to fourth grade.

Debate Over Its Independence

Bulgarian scholars often consider Macedonian to be part of the Bulgarian dialect area. Many Bulgarian and international sources before World War II referred to the Slavic dialects in today's North Macedonia and Northern Greece as a group of Bulgarian dialects. Some scholars argue that the idea of a separate Macedonian language appeared in the late 19th century with the rise of Macedonian nationalism. The need for a separate standard Macedonian language then came in the early 20th century. Local names for the language also included balgàrtzki, bùgarski, or bugàrski, meaning Bulgarian.

Even though Bulgaria was the first country to recognize North Macedonia's independence, most Bulgarian academics and the public still see the language spoken there as a form of Bulgarian. Bulgarian dialect experts call the Macedonian language a "Macedonian linguistic norm of the Bulgarian language."

In 1999, the Bulgarian government signed a Joint Declaration in the official languages of both countries. This was the first time Bulgaria agreed to sign a bilateral agreement written in Macedonian. As of 2019, debates about the language and its origins continue in academic and political groups in both countries.

Macedonian is still widely seen as a dialect by Bulgarian scholars, historians, and politicians. This includes the Government of Bulgaria and the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. They deny the existence of a separate Macedonian language and call it a written regional form of the Bulgarian language. Most of the Bulgarian population shares these views.

However, the general international view outside of Bulgaria is that Macedonian is an independent language within the Eastern South Slavic dialect group. It is recognized by 138 countries of the United Nations.

Naming Debate

The Greek scientific and local community has been against using the name "Macedonian" for the language. This is because of the Greek-Macedonian naming dispute. The term is often avoided in Greece and strongly rejected by most Greeks. For them, "Macedonian" has very different meanings. Instead, the language is often simply called "Slavic" or "Slavomacedonian" (translated to "Macedonian Slavic" in English).

Speakers themselves call their language makedonski, makedoniski ("Macedonian"), slaviká (Greek: σλαβικά, "Slavic"), dópia or entópia (Greek: εντόπια, "local/indigenous [language]"), balgàrtzki (Bulgarian) or "Macedonian" in some parts of Kastoria. In parts of Dolna Prespa, they use bògartski ("Bulgarian") along with naši ("our own") and stariski ("old").

With the Prespa agreement signed in 2018 between the Government of North Macedonia and the Government of Greece, Greece accepted the use of the adjective "Macedonian" to refer to the language. However, they added a footnote to describe it as Slavic.

Gallery

-

The 11th century Codex Zographensis, a text written in Old Church Slavonic using the Glagolitic writing system.

-

Dictionary of four Balkan languages (Greek, Aromanian, Bulgarian and Albanian) written in Moscopole c. 1770 and published c. 1794; republished in 1802 in Greek.

-

The Young Macedonian Literary Society magazine Loza issued in 1891. Its appeal was to present the Macedonian dialects much more in the standard Bulgarian language. The magazine was banned as separatist by the authorities.

-

Front cover of Za Makedonckite Raboti. In 1903 Krste Misirkov argued for the codification of a standard literary Macedonian language in it.

-

Issue of the IMRO newspaper "Svoboda ili smart" from April 1933. All official documents of the Macedonian revolutionary organization from its foundation in 1893 until its ban in 1934 were in standard Bulgarian.

See also

- Macedonian alphabet

- History of North Macedonia

- Political views on the Macedonian language

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |