Kwakʼwala facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Kwakʼwala |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kwakiutl Kwak̓wala |

||||

Marianne Nicolson's The House of the Ghosts, 2008. Text in Kwakʼwala and English at the Vancouver Art Gallery

|

||||

| Native to | Canada | |||

| Region | along the Queen Charlotte Strait | |||

| Ethnicity | 3,665 Kwakwakaʼwakw | |||

| Native speakers | 150 (2021 census) | |||

| Language family |

Wakashan

|

|||

| Dialects |

T̓łat̓łasik̓wala

G̱uc̓ala

Nak̕wala

|

|||

Dialects of Kwakʼwala

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

| People | Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw |

|---|---|

| Language | Kwak̓wala Kwak̓wala ʼNak̓wala G̱uc̓ala T̓łat̓łasik̓wala Liqʼwala |

| Country | Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw A̱wi'nagwis |

Kwakʼwala (pronounced kwok-wah-la) is the traditional language of the Kwakwakaʼwakw people. They live along the Queen Charlotte Strait in Western Canada. The language was also known in the past as Kwakiutl.

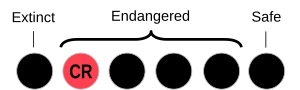

Today, about 150 people speak Kwakʼwala. It is considered a critically endangered language. This means there is a risk it could disappear. However, many people are working hard to save it and teach it to new generations.

Contents

History of Kwakʼwala

For thousands of years, Kwakʼwala was passed down orally, through stories and songs. It did not have a written form until Europeans arrived in the area.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the Canadian government created policies that made it very difficult for the Kwakwakaʼwakw to practice their culture and speak their language. Children were often sent to special schools where they were not allowed to speak Kwakʼwala. These actions caused the number of speakers to drop significantly.

Today, elders and new learners are working together to bring the language back to their communities.

Keeping the Language Alive

There is a strong movement to bring Kwakʼwala back. Many exciting projects are helping people learn and speak the language again.

- Language Nests and Schools: Places like the Tʼlisalagiʼlakw School and the Uʼmista Cultural Center in Alert Bay, British Columbia, teach Kwakʼwala to both children and adults.

- Culture Camps: Special camps, like Nawalakw (which means "Supernatural"), let young people learn the language while also learning about their culture and traditions.

- Technology: To help more people learn, there is a Kwakʼwala iPhone app and an online dictionary at the First Voices website. Researchers are even creating virtual reality tools to make learning more fun.

Dialects of Kwakʼwala

The Kwakwakaʼwakw people are made up of several different tribes. While they all share the Kwakʼwala language, some tribes speak it a little differently. This is similar to how English has American, British, and Australian accents. These different ways of speaking are called dialects.

The four main dialects of Kwakʼwala are:

- Kwak̓wala

- ʼNak̓wala

- G̱uc̓ala

- T̓łat̓łasik̓wala

Another related language, Liqʼwala, is spoken by other Kwakwakaʼwakw tribes. Some people consider it a dialect of Kwakʼwala, while others see it as a separate language.

Cool Features of the Language

Kwakʼwala is a very complex and fascinating language. It has some amazing features that make it different from English.

Unique Sounds

Kwakʼwala has a large alphabet with many consonant sounds that might be new to English speakers.

- It has sounds made much further back in the throat than we are used to.

- It uses special "popping" sounds called ejectives. These are made by building up air pressure in the mouth and releasing it with a pop.

- It also has sounds that are "glottalized," which means they are made with a quick closure of the throat, like the sound in the middle of "uh-oh!"

Super Long Words

One of the most interesting things about Kwakʼwala is that it is a polysynthetic language. This is a way of saying it can build very long words that express a whole sentence's worth of ideas.

This is done by starting with a main word (a root) and adding many different parts (suffixes) to the end. Each suffix adds a new piece of meaning, like who is doing the action, where it's happening, or when. This makes the language very efficient and precise.

Writing Kwakʼwala

For most of its history, Kwakʼwala was only a spoken language. In the late 1800s, European missionaries and scholars like Franz Boas and his partner George Hunt began to write it down. They created alphabets to capture its many unique sounds.

At first, these writing systems were very complicated and hard to use. Later, a more practical alphabet was developed so that Kwakwakaʼwakw people could easily read and write their own language. Today, the most common alphabet used is the one promoted by the Uʼmista Cultural Society. It uses letters from the English alphabet plus some extra marks to represent all the special sounds in Kwakʼwala.

Uʼmista Cultural Society Alphabet

| Uppercase | A | A̱ | B | D | Dł | Dz | E | G | Gw | G̱ | G̱w | H | I | K | Kw | K̓ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowercase | a | a̱ | b | d | dł | dz | e | g | gw | g̱ | g̱w | h | i | k | kw | k̓ |

| Uppercase | K̓w | Ḵ | Ḵw | Ḵ̓ | Ḵ̓w | L | ʼL | Ł | M | ʼM | N | ʼN | O | P | P̓ | S |

| Lowercase | k̓w | ḵ | ḵw | ḵ̓ | ḵ̓w | l | ʼl | ł | m | ʼm | n | ʼn | o | p | p̓ | s |

| Uppercase | T | T̓ | Tł | T̓ł | Ts | T̓s | U | W | ʼW | X | Xw | X̱ | X̱w | Y | ʼY | ʼ |

| Lowercase | t | t̓ | tł | t̓ł | ts | t̓s | u | w | ʼw | x | xw | x̱ | x̱w | y | ʼy | ʼ |

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |