Leo Kanner facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Leo Kanner

|

|

|---|---|

Leo Kanner, ca. 1955

|

|

| Born |

Chaskel Leib Kanner

June 13, 1894 Klekotów, Austria-Hungary

|

| Died | April 3, 1981 (aged 86) |

| Medical career | |

| Profession | Physician |

| Field | Psychiatry |

| Institutions | Johns Hopkins Hospital, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine |

| Sub-specialties | Child & Adolescent Psychiatry |

| Research | Autism spectrum disorder |

| Notable works | Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact (1943) |

Leo Kanner (born Chaskel Leib Kanner; June 13, 1894 – April 3, 1981) was an important Austrian-American psychiatrist and doctor. He is best known for his groundbreaking work on autism. He also helped many people as a social activist.

Contents

Who Was Leo Kanner?

His Early Life and Education

Leo Kanner was born as Chaskel Leib Kanner in Klekotów, Austria-Hungary (which is now Klekotiv, Ukraine) on June 13, 1894. His parents were Abraham and Clara Kanner. Many people in his hometown were Jewish, and Leo grew up in a Jewish family. He didn't like his birth names, "Chaskel" and "Lieb," so he chose to go by "Leo."

When he was 12, in 1906, Leo moved to Berlin to live with his uncle. Later, his family joined him there. From a young age, Leo loved the arts and wanted to be a poet. However, he couldn't get his poems published.

In 1913, Leo finished high school at the Sophien-Gymnasium in Berlin. He was very good at science. He then started medical school at the University of Berlin. His studies were paused during World War I, when he joined the Austro-Hungarian Army as a medic. After the war, he went back to medical school and became a doctor in 1921. That same year, Leo married June Lewin. They had two children, Anita and Albert.

Starting His Medical Career

After medical school, Kanner worked as a cardiologist (a heart doctor) at the Charité Hospital in Berlin. He studied how normal heart sounds related to the electrocardiogram, a test that checks heart activity. The Charité Hospital was a leading place for science and patient care, attracting doctors and scientists from all over the world.

In 1924, Kanner moved to the United States. He was motivated by the difficult economic times in Germany after the war. He later said that if he had stayed in Germany, he might have been harmed by the Nazis during The Holocaust.

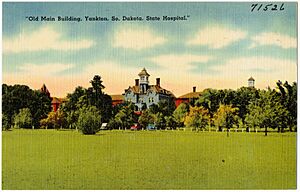

When he arrived in the U.S., he started working at the state hospital in Yankton, South Dakota. Here, he began to learn about pediatrics (children's health) and psychiatry (mental health), which were new fields for him. To get better at English, he did crossword puzzles from The New York Times. In South Dakota, Kanner published his first works about general paralysis. He also studied how a substance called adrenalin affected blood pressure. In 1928, he published his first book, Folklore of the Teeth, which looked at dental practices and customs around the world.

Working at Johns Hopkins

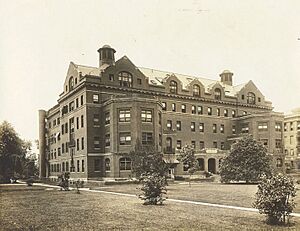

In 1928, after four years in South Dakota, Kanner moved to Baltimore, Maryland. He got a special position at the The Henry Phipps Psychiatric Clinic at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. This happened because Adolf Meyer, a leading psychiatrist, noticed his work.

In 1930, with support from foundations, Meyer and Edward A. Park created the Children's Psychiatry Service at Johns Hopkins. This was the first child psychiatry clinic in the United States. Kanner was chosen to lead this new program. Even though he was new to child psychiatry, he taught himself a lot. In 1933, Kanner became an associate professor of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins University. In 1935, he published his textbook, Child Psychiatry, which was the first English book on the subject.

Beyond his important research, Kanner also worked as a social activist. He cared deeply about people with mental health challenges. In the 1930s, some lawyers and judges arranged for 166 mentally ill people to be released from state hospitals. They were then made to work as unpaid servants for rich families. Kanner was worried about these people. He tracked them down and found that many had terrible problems, including illnesses, imprisonment, or even death. He also found that these 166 people had 165 children, many of whom became orphans or died because they were neglected.

Kanner's report on these patients made headlines in newspapers like The Baltimore Sun and The Washington Post in 1938. This news helped bring about community action and led to better treatment for people with mental illnesses. During World War II, Kanner also helped hundreds of Jewish doctors escape the Nazis by helping them move to work in the United States. He and his wife even opened their home to many of these refugees.

Kanner's Research on Autism

Starting in 1938, Kanner carefully studied eleven of his young patients. He wrote down their lives and behaviors in a very important paper published in 1943. This paper was called "Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact." In this landmark work, Kanner described these children, all born in the 1930s. They lived very different lives but seemed to share something he called "infantile autism," which we now simply call autism.

Kanner led the Child Psychiatry department at Johns Hopkins until he retired in 1959. After retiring, he continued to publish papers about autism until 1973. He also taught as a visiting professor at other universities and had a busy consulting practice until a few years before he passed away.

Understanding "Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact" (1943)

Kanner's paper, "Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact," was published in the journal Nervous Child. It became one of the most referenced papers on autism in the 20th century. In this paper, Kanner used the word "autism," which had been used before by Eugen Bleuler to describe inward symptoms in adults with schizophrenia. However, Kanner used it to describe the eleven children in his study, calling it "infantile autism."

Kanner made it clear that his observations of "autism" were different from schizophrenia. He explained that autism was not an early form of schizophrenia, and that the signs of autism were clear from birth or very early in life. This important paper, sometimes called "Kanner Syndrome," became the basis for future research on what is now known as autism spectrum disorder.

Kanner pointed out that the main challenge for children with autism was their difficulty in relating to people and objects in a typical way from birth.

He also noticed that speech problems were central to this condition. Many children had delayed speech. Those who could speak often used language in unusual ways. For example, they might repeat phrases exactly (this is called echolalia) or use language very strictly, like always repeating pronouns.

Kanner also saw that the children's behavior was driven by a strong desire for things to stay the same. This led them to repeat actions, sounds, and have limited spontaneous play. He also noted that many of the children had excellent rote memory, meaning they could remember facts, lists, or songs very well. Some parents would teach them many facts. Kanner also mentioned that four of the eleven children were thought to be deaf or hard of hearing when they were very young. He also reported early difficulties with eating. He suggested that eating might have been the first time their extreme aloneness was interrupted. He noted that the children were generally healthy and had normal brain scans (EEGs). However, he did observe that 5 of the 11 children had somewhat large heads, and a few were a bit clumsy when they walked.

When talking about the children's families, Kanner noticed that many parents and relatives were very intelligent. However, he also felt that there were few warm-hearted parents among the families he observed. He wondered if parenting might play a role in autism. But he also balanced this idea by noting that the children's aloneness was present very early on. This made it unlikely that parenting was the only cause of the condition.

Other Important Studies

In 1949, Kanner published another important study called "Problems of Nosology and Psychodynamics of Early Infantile Autism." In this paper, he looked at how "early infantile autism" fit into the classification of mental health conditions. Kanner focused on how early infantile autism was similar to, and different from, other conditions like dementia infantilis and childhood schizophrenia.

While early infantile autism and childhood schizophrenia have very similar signs, Kanner argued that they are different in when they start. Childhood schizophrenia usually begins after a period of normal development. However, early infantile autism appears almost right after birth. Kanner reported that babies with early infantile autism were often unusually quiet, didn't respond normally to people, didn't get ready to be picked up, were startled by anything that disturbed their quietness, and lacked responsiveness.

Kanner also wondered if infantile autism could be seen as the "earliest possible manifestation of childhood schizophrenia." Unlike his other studies, Kanner looked closely at the parents of the children. He found an interesting pattern: most of the parents had very successful careers, such as scientists, professors, artists, or business leaders. In fact, Kanner had trouble finding autistic children whose parents were not highly educated. This made Kanner curious about the parents' attitudes and their relationships with their children. He found that most parents had distant, almost mechanical relationships with their autistic children and sometimes ignored them. Kanner thought that this lack of affection might cause the autistic children to withdraw and "seek comfort in solitude." He even suggested that the children's strong interests and amazing memory skills might be "a plea for parental approval."

His Legacy and Impact

Leo Kanner passed away on April 3, 1981, from heart failure in Sykesville, Maryland. During his life, Kanner helped create the field of child psychiatry. His research laid the groundwork for studies in psychology, pediatrics, autism, and adolescent psychiatry. He is now known as the Father of Child Psychiatry.

Kanner was the first doctor in the United States to be officially called a child psychiatrist. His textbook, "Child Psychiatry" (1935), was the first English book to focus on children's mental health problems. In 1943, he was the first to describe the condition of early infantile autism. His clear descriptions of children with autism are still used today to help understand and diagnose the condition. During his lifetime, Kanner published over 250 articles and eight books on psychiatry, pediatrics, psychology, and the history of medicine.

Since Kanner first described childhood autism, research on the topic has grown a lot. Even though much progress has been made, this field is still developing. Many new areas of research are just beginning. Despite the time that has passed, the condition Kanner identified and his observations about the children he studied are still important today. While some of his early ideas about the causes of autism were based on the thinking of his time, many of his observations were very insightful.

Today, studies on autism often focus on the genetic reasons behind the condition. There has been a lot of research into changes in DNA and other genetic factors that might lead to autism. Also, research into environmental factors and brain structure helps us understand all the parts involved in autism. These promising research paths all stem from Leo Kanner's life work.

To honor Dr. Kanner's contributions, all Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Fellows at Johns Hopkins are now called Kanner fellows. The Dr. Leo Kanner Award was created by The Mind Research Foundation to recognize those who help children with autism and their families. Many buildings, schools, and institutes in the United States and other countries are named after Leo Kanner.

Awards and Recognition

- First Award given by the National Organization for Mentally Ill Children in 1960

- Gutheil Memorial Medal by the Association for the Advancement of Psychotherapy in 1962

- Stanley R. Dean Award by the Fund for Behavioral Sciences in 1965

- Agnes Bruce Greig Award in 1965

- Agnes Purcell McGavin Award by the American Psychiatric Association in 1967

- Citation from the National Society for Autistic Children in 1969

- Salmon Award by New York Academy of Medicine in 1974

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Leo Kanner para niños

In Spanish: Leo Kanner para niños

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |