Lorenz Oken facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Lorenz Oken

|

|

|---|---|

Lorenz Oken

|

|

| Born |

Lorenz Okenfuß

1 August 1779 |

| Died | 11 August 1851 (aged 72) Zurich, Switzerland

|

| Nationality | German |

| Alma mater | University of Freiburg University of Würzburg |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Natural history |

| Influenced | Étienne Saint-Hilaire (1772–1844) |

Lorenz Oken (born August 1, 1779 – died August 11, 1851) was a German scientist. He studied nature, plants, animals, and birds. He was known for his ideas about how living things are connected.

Oken was born Lorenz Okenfuss in a place called Bohlsbach, which is now part of Offenburg, Germany. He studied natural history and medicine at the universities of Freiburg and Würzburg. Later, he went to the University of Göttingen. There, he became a lecturer and shortened his name to Oken.

In 1802, Lorenz Oken published a small book. It was called Grundriss der Naturphilosophie, der Theorie der Sinne, mit der darauf gegründeten Classification der Thiere. This book was the first of many that made him a leader in a science movement called "Naturphilosophie" in Germany.

Oken's ideas were based on the work of other thinkers. He believed that all of nature followed certain rules. He tried to connect these rules to how the physical world works.

Oken also wrote a seven-volume book series. It was called Allgemeine Naturgeschichte für alle Stände. This series, published between 1839 and 1841, included many detailed pictures.

Contents

Oken's Animal Classification System

In his 1802 book, Oken shared his ideas for classifying animals. He believed that animal groups were based on their sense organs. He thought there were only five main classes of animals:

- Dermatozoa: These were animals without a backbone, like insects or worms.

- Glossozoa: These were fish, the first animals with a true tongue.

- Rhinozoa: These were reptiles, the first animals where the nose opens into the mouth.

- Otozoa: These were birds, the first animals with ears that open to the outside.

- Ophthalmozoa: These were mammals, which have all sense organs complete, including movable eyes with eyelids.

Ideas on How Life Begins

In 1805, Oken wrote a book about how living things are formed. He suggested that all living things start from tiny bubbles or cells. He called these bubbles "infusorial mass" or "protoplasma." He believed that larger organisms grew from these tiny bubbles joining together.

A year later, in 1806, Oken continued to develop his ideas. He showed that the intestines in animals grow from a part called the umbilical vesicle. This part is like the yolk sac in an egg. Another scientist, Caspar Wolff, had seen this in chicks before. But Oken showed how this discovery fit into his larger system of how life develops.

Oken at the University of Jena

In 1807, Oken was invited to teach at the University of Jena. He became a professor of medical sciences. For his first lecture, he talked about his ideas on the "Significance of the Bones of the Skull."

Oken said he got this idea in 1806 while walking in a forest. He found a deer skull and realized that the bones of the skull looked like a backbone. He thought the skull was like a modified part of the spine.

Oken's lectures at Jena were very popular. He taught about natural philosophy, zoology, anatomy, and the way humans, animals, and plants work. He believed that the entire universe and all living things were connected. He also had ideas about light and heat, suggesting they were forms of energy.

In 1809, Oken applied his system to minerals. He grouped them by how they combined with other elements, not just by the metals they contained.

In 1810, he put all his ideas about nature into one big system. He wrote a book called Lehrbuch der Naturphilosophie. In this book, he tried to show that minerals, plants, and animals should be grouped based on their main organs or body systems. He believed that everything in nature followed certain numerical rules, like in chemistry. Because of this book, he was given the title of "court-councillor" and became a full professor in 1812.

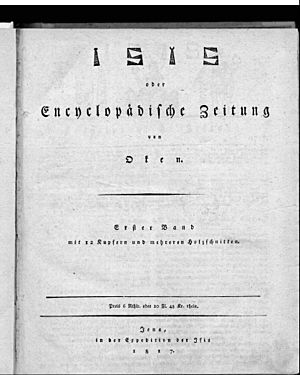

The Isis Journal

In 1816, Oken started a famous science magazine called Isis. It covered natural sciences, anatomy, and physiology. Sometimes, it even included poetry and comments on politics. This caused problems with some governments. The court of Weimar told Oken he had to stop publishing Isis or leave his job. He chose to leave his job.

Even though Isis was banned in Weimar, Oken found a way to keep publishing it in another town until 1848.

In 1821, Oken suggested in Isis that German scientists should have annual meetings. This idea led to the first meeting of the Society of German Natural Scientists and Physicians in 1822. The British Association for the Advancement of Science was later created using Oken's idea as a model.

In 1828, Oken started teaching again at the University of Munich. He became a professor there. In 1832, he moved to Switzerland and became a professor of natural history at the University of Zürich in 1833. He lived there and continued his scientific work until he passed away.

Ideas on Body Structure

Oken believed that the head was a kind of repetition of the body's trunk. He thought the brain was like the spinal cord, the skull was like the backbone, and the jaws were like limbs. He saw the head as a smaller version of the whole body.

Other scientists, like Johann von Autenrieth and Carl Kielmeyer, had similar ideas. But Oken used these ideas to support his larger philosophical system. He believed that "all is in all" and "all is in every part."

Later, another scientist named Sir Richard Owen developed these ideas further. He showed that the head is not a full repetition of the trunk. Instead, it's made of modified parts of the body. He explained that the jaws are not limbs of the head, but rather parts of the first two segments of the body.

There was some debate about who first came up with the idea that the skull bones are related to vertebrae. The famous writer Johann von Goethe also claimed to have had this idea. However, Oken's account of his discovery in 1806, finding a deer skull in the forest, is very similar to Goethe's story of finding a sheep skull in Venice. It's likely that Oken came up with the idea independently.

In 1832, Oken was made a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Works

- Allgemeine Naturgeschichte für alle Stände . Vol.1-8 . Hoffmann, Stuttgart 1833-1843 Digital edition by the University and State Library Düsseldorf

- Abbildungen zu Okens allgemeiner Naturgeschichte für alle Stände . Hoffmann, Stuttgart 1843 Digital edition by the University and State Library Düsseldorf

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Lorenz Oken para niños

In Spanish: Lorenz Oken para niños