Lucy Walker steamboat disaster facts for kids

The Lucy Walker steamboat disaster was a terrible accident that happened in 1844 on the Ohio River, near New Albany, Indiana. The steamboat Lucy Walker exploded because its boilers blew up. This happened on the afternoon of Wednesday, October 23, 1844. The explosion caused a big fire and the boat quickly sank. This disaster was one of many similar accidents that led to important new laws and safety rules for steamboats. The boat's owner was a Native American man, and its crew were African-American slaves. The passengers were a mix of people traveling on the frontier.

Contents

About the Steamboat Lucy Walker

The Lucy Walker was a typical steamboat for its time. It was about 44 meters (144 feet) long and 7.5 meters (24 feet, 6 inches) wide. It weighed 183 tons. The boat was built in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1843. Its home port was Webbers Falls on the Arkansas River, which was part of the Cherokee Nation at the time. The Lucy Walker often traveled to cities like Louisville, Kentucky and New Orleans, Louisiana. It was a side-wheeler, meaning it had paddle wheels on its sides. It had three boilers and one deck.

The boat had several captains over time. Captain Thomas J. Halderman was very experienced, having worked on steamboats since 1820. However, for some reason, he was replaced just before the final trip. The boat's owner, Joseph Vann, took over as captain.

The Final Journey

The Lucy Walker left the Louisville dock around noon on Wednesday, October 23, 1844. It was heading for New Orleans. Some passengers might have been talking about the upcoming election between Henry Clay and James K. Polk. The boat likely used the new Louisville and Portland Canal to get past the rapids known as the "Falls of the Ohio." After that, it stopped at New Albany, Indiana, to pick up more passengers.

The Explosion and Fire

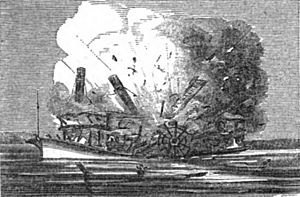

Around 5:00 PM that day, the boat's engines stopped. The Lucy Walker was drifting in the middle of the river, about 4 to 5 kilometers (2.5 to 3 miles) below New Albany. Some repairs were being made. Suddenly, all three boilers exploded with a huge blast! Pieces of metal flew everywhere. The boat caught fire and quickly sank in about 3.6 meters (12 feet) of the Ohio River.

The water soon filled with people from the Lucy Walker, both living and dead. Many were badly hurt or burned. Luckily, Captain L.B. Dunham and his crew from a nearby boat called the Gopher helped rescue survivors. The Gopher was a special boat that removed obstacles from the river.

People at the time understood that steamboats could sink from crashes or fires. But boiler explosions seemed mysterious. After the Lucy Walker disaster, newspapers wondered what caused it. Some thought a broken pump or low water in the boiler was to blame. Others worried about careless officers or poorly built boilers. Later, some wondered if steamboat racing might have played a part in the disaster.

The Lucy Walker disaster was not the worst steamboat accident in American history, but it was one of the deadliest. More than 100 people might have died that day.

New Laws for Safety

The many deaths from steamboat disasters like the Lucy Walker made the public very concerned. People started talking about insurance, helping victims, and the responsibilities of boat owners and captains. There were also discussions in Congress about needing new laws.

One big problem was that steamboat operators didn't fully understand how boilers worked. In those early days, people didn't know much about the strength of metals. Engineers didn't understand how things like mud could affect pumps. Safety valves could be overloaded, and there weren't many pressure gauges. If the water level in boilers got too low, the boiler walls could overheat. Sometimes, owners were too cheap or greedy to buy good equipment or hire skilled workers.

An earlier law from 1838 about steamboat safety was not enough. So, a much stronger law was passed in 1852. This new law required boilers to be tested with water pressure. It also set limits on how much pressure boilers could handle. Boiler parts had to be inspected when they were made. Also, engineers had to be tested and get special licenses. Later laws led to the creation of the Steamboat Inspection Service, which helped make steamboat travel much safer. The government even funded scientific research to study why boilers exploded. This was one of the first times the government paid for pure scientific research.

The Owner and His Boat

The official government paper for the Lucy Walker said that Joseph Vann swore he was a U.S. citizen from Arkansas. But this was not true. He was a citizen of the Cherokee Nation from Indian Territory. Joseph Vann was known as "Rich Joe" Vann because he had inherited a lot of money from his father. He owned a famous racehorse named "Lucy Walker." He probably bought her in 1839. This horse won many races and had many foals (baby horses) that Vann sold for a lot of money. When he bought a steamboat in 1843, Vann named it after his favorite horse. We don't know if the horse was on the boat that day.

In February 1843, Vann advertised his new steamboat. He said it was "new fast running" and had a "sheet metal roof." In March 1843, the Lucy Walker carried 200 Seminole Indians from New Orleans to Fort Gibson. The U.S. Army had captured these Indians in Florida as part of a plan to move southern Indian tribes to Indian Territory. Five years before, other steamboats had carried Vann's fellow Cherokees to the West as part of the sad journey known as the Trail of Tears.

The Crew

Joseph Vann owned many African-American slaves. In 1835, he owned 110 slaves. By 1842, he owned several hundred slaves. They worked on his farm, took care of his horses, operated his ferryboat, or worked as crew on the Lucy Walker.

In November 1842, about 25 slaves belonging to Vann and other wealthy Cherokees tried to escape. They locked their owners in their homes and tried to run to Mexico. Other slaves joined them, but they were quickly caught by a group of Cherokees. Vann then made these slaves work as crew on the Lucy Walker. He wanted to keep them away from his other slaves. One of these slaves was named Kalet or Caleb Vann. In 1937, his daughter, Mrs. Betty Robinson, said that her father was killed in the Lucy Walker accident.

Another former slave, Lucinda Vann, told a story about Jim Vann, who was an engineer or fireman on the steamboat. She said Captain Vann forced Jim at gunpoint to throw slabs of meat into the boiler. The idea was that the fat would make the boiler water super hot and increase steam pressure. Lucinda Vann said that Jim Vann threw the meat into the firebox and then jumped overboard just before the boilers exploded.

After the Disaster

A geologist named Albert C. Koch was in Louisville the day after the explosion. He was told that 106 people died, and many were badly hurt or burned.

The story of the Lucy Walker disaster is well known, but many details are different in various accounts. Eyewitnesses included Captain Dunham of the Gopher and a group of ministers who were on the Lucy Walker. These ministers talked about their experiences but did not mention that the boat's owner was a Native American. Most newspaper stories also did not mention this. The owner was often wrongly identified as Captain David Vann. Estimates of how many people died range widely from 18 to more than 100. Even the date of the accident is often listed incorrectly in many books. Only the Cherokee sources clearly explain Joseph Vann's role in the sudden end of the Lucy Walker and his own death.

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |