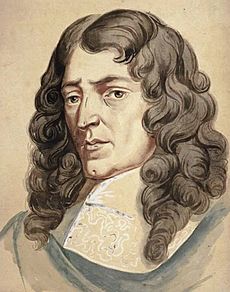

Marc-Antoine Charpentier facts for kids

Marc-Antoine Charpentier (born in 1643 – died on 24 February 1704) was a famous French Baroque composer. He lived during the time of Louis XIV, a powerful king of France.

One of Charpentier's most well-known pieces is the main tune from his Te Deum. It's called Marche en rondeau. You might have heard it! This tune is still used today as a special fanfare for television broadcasts by the Eurovision Network, which is part of the European Broadcasting Union.

Marc-Antoine Charpentier was a very important composer in France during the 1600s. He wrote many different kinds of music. People especially admired his skill in writing religious music for voices.

He started his career by traveling to Italy. There, he learned a lot from Italian composers like Giacomo Carissimi. This Italian style stayed with him throughout his life. He was one of the few French composers who wrote oratorios, which are like musical stories, usually religious.

In 1670, he became a music master for the Duchess of Guise. Later, around 1690, Charpentier wrote an opera called Médée. This opera was not very successful, which led him to focus more on religious music. He became the composer for several religious groups, including the Carmelites and the Montmartre Abbey.

In 1698, Charpentier was chosen to be the music master for the children of the Sainte-Chapelle du Palais. He also worked with the famous playwright Molière. After Molière had some disagreements with another composer, Jean-Baptiste Lully, he asked Charpentier to write music for his plays. This included music for Circe, Andromeda, and The Imaginary Invalid.

Charpentier wrote many different types of music. He composed secular works (non-religious), music for the stage, operas, cantatas (pieces for singers and instruments), sonatas (instrumental pieces), and symphonies. He also wrote a lot of sacred (religious) music. This included motets, oratorios, masses, psalms, Magnificats, and Litanies.

When he died, Charpentier had written about 800 musical pieces. However, only 28 special books of his original handwritten music still exist today. These books contain more than 500 pieces that he carefully organized himself. This collection, called Mélanges, is one of the most complete sets of a composer's own handwritten music ever found.

Biography

Charpentier was born in or near Paris. His father was a skilled writer who knew important families in the Parliament of Paris. Marc-Antoine received a very good education, possibly with help from the Jesuits. When he was eighteen, he even signed up for law school in Paris, but he left after only one semester.

He spent about "two or three years" in Rome, Italy, probably between 1667 and 1669. There, he studied with Giacomo Carissimi, a well-known composer. He also met other musicians and poets. There's a story that Charpentier first went to Rome to study painting, but Carissimi discovered his musical talent. This story isn't proven, but he definitely learned a lot about Italian music and brought that knowledge back to France.

When he returned to France, Charpentier likely started working for Marie de Lorraine, duchesse de Guise. She was often called "Mlle de Guise." She gave him a special "apartment" in her home, the Hôtel de Guise. This shows that Charpentier was not just a regular servant, but an important person in her court.

For the next seventeen years, Charpentier wrote a lot of music for Mlle de Guise. This included settings of Psalms, hymns, motets, a Magnificat, a mass, and a Dies Irae for a funeral. He also wrote many Italian-style oratorios. Charpentier preferred to call these "canticum" instead of "oratorio."

During the 1670s, most of his works were for trios (three performers). This usually meant two women and a male singer, plus two instruments and a continuo (a bass instrument and a keyboard). If the music was for a male monastery, he would write for three male voices. Around 1680, Mlle de Guise made her music group larger, with 13 performers and a singing teacher.

During his time with Mlle de Guise, Charpentier also composed for "Mme de Guise", who was King Louis XIV's cousin. Thanks to Mme de Guise's support, Charpentier's chamber operas could be performed. This was important because Jean-Baptiste Lully had a special right to control all theatrical music. Most of Charpentier's French operas and pastorales from 1684 to 1687 were probably ordered by Mme de Guise for court events.

By late 1687, Mlle de Guise was very ill. Around this time, Charpentier began working for the Jesuits. He was not mentioned in her will, which suggests she had already rewarded him and approved of his leaving.

Even while working for Mlle de Guise, Charpentier took on many other music jobs. For example, after Molière and Jean-Baptiste Lully had a disagreement in 1672, Molière asked Charpentier to write music for his plays. Charpentier continued to write for Molière's successors, Thomas Corneille and Jean Donneau de Visé. He often wrote pieces that needed more musicians than Lully's rules allowed. By 1685, these restrictions became too strict, and Charpentier stopped writing for spoken theater.

In 1679, Charpentier was chosen to compose for King Louis XIV's son, the Dauphin. He wrote religious pieces for the prince's private chapel. By early 1683, he received a royal pension (money from the king). He was also asked to write music for important court events like the annual Corpus Christi procession. In April of that year, he became so sick that he had to drop out of a competition to become a sub-master of the royal chapel. His notebooks show he wrote nothing for several months, which proves he was too ill to work.

From late 1687 to early 1698, Charpentier was the maître de musique (music master) for the Jesuits. He worked first for their school, Louis-le-Grand, and then for the church of Saint-Louis. At Saint-Louis, he mostly wrote musical settings of psalms and other religious texts. During these years, his works often used large groups of musicians, including paid singers from the Royal Opera. He also taught music to Philippe, Duke of Chartres.

In 1698, Charpentier was appointed maître de musique for the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris. This was a royal job he held until he died in 1704. One of his famous pieces from this time was the Mass Assumpta Est Maria (H. 11). Most of his music from 1690 to 1704 has not survived. This is because when a music master died, the royal government usually took everything they had written for the Chapel. Charpentier died at the Sainte-Chapelle and was buried in a small cemetery behind the chapel's choir. This cemetery no longer exists.

In 1727, Charpentier's family sold his handwritten music books (28 large volumes) to the Royal Library, which is now the Bibliothèque nationale de France. These books, known as the Mélanges, were organized by Charpentier himself. They have helped experts learn when his pieces were written and for what events.

Music, style and influence

Charpentier's music includes oratorios, masses, operas, and many smaller pieces. Many of his shorter works for one or two voices and instruments are similar to Italian cantatas. He called them airs sérieux or airs à boire if they were in French, but cantata if they were in Italian.

Charpentier lived during a special time in music history. It was a "transition period" where older musical styles and newer ones mixed together. He was also a respected music expert. He wrote a guide for teaching music to Philippe d’Orléans, the Duke of Chartres, around 1691. This guide was later expanded. In 2009, another of his handwritten guides was found, suggesting he wrote many such books over almost two decades.

Modern significance

The opening part, or prelude, of his Te Deum, H.146, is a rondo. This tune is the official theme music for the European Broadcasting Union. You hear it at the beginning of Eurovision events. This theme was also used as the intro for The Olympiad films by Bud Greenspan.

Honors

An asteroid discovered in May 1997 by Paul G. Comba in Arizona, USA, was named 9445 Charpentier (1997 JA8) by NASA.

See also

In Spanish: Marc-Antoine Charpentier para niños

In Spanish: Marc-Antoine Charpentier para niños