March law (Anglo-Scottish border) facts for kids

March law, also known as Marcher law, was a special set of rules used to solve problems between people living near the border of England and Scotland. This system worked from the Middle Ages up to the early 1600s. The word "march" means "boundary," and these laws helped manage disputes in the Anglo-Scottish borderlands. They were mainly about dealing with crimes committed by people from one country in the other's territory and getting back stolen items.

These laws were managed by special officials called the Wardens of the Marches. They handled things during wars and also during times of peace. The courts met at specific places along the border on days called "days of march" or "days of truce." People who had complaints, the accused, and jurors from both England and Scotland would all gather.

In England, March law worked alongside the usual English law, but it was often clearer and more helpful for border issues. March law also included ideas from fairness and military rules. It was most important during truces, as during wars, England often didn't recognize Scotland's separate legal system.

Contents

Why March Law Was Needed

From the late 1200s until 1603, the border areas between England and Scotland were often filled with fighting. England wanted to control Scotland, and Scotland resisted. Also, Scotland often helped France in its wars against England.

Local groups, known as Border Reivers, would often cross the border. They would steal animals, take people captive, and damage property. This happened even during times of peace. Because of this constant danger, people found it hard to farm or raise animals, as they might be stolen.

Normal laws didn't work well here. Criminals could just cross the border to escape justice. There was no easy way for victims to get their stolen goods back or receive payment for damages. This is why March law was so important. It offered a way to get justice when regular laws couldn't.

How March Law Started

The exact start of March law is a bit of a mystery. The first written rules were made in 1249. Twelve knights, six from England and six from Scotland, met at the border. They wrote down the "laws and customs of the march" because Henry III of England and Alexander II of Scotland wanted them to. These rules seemed to be based on practices that had been around for a while.

The 1249 rules covered several things:

- How to announce a crime on both sides of the border.

- Using promises to make sure people showed up for court.

- Using jurors from both England and Scotland.

- Paying victims for their losses, even for murder.

- How to prove innocence in a dispute, often through a fight called "wager of battle."

- Giving safety to those who confessed.

Most of these rules focused on catching criminals.

Before the Wardens were set up, border disputes were often handled by the local sheriff. But this was often not enough, so March law became a better option.

March Law Over Time

Changes in the 1300s

When Edward I of England came to power, there was a lot of fighting with Scotland. March law was put on hold for a while. But by the mid-1300s, it started to be used again. The Wardens, who were first in charge of military matters, began to take on judicial roles during peacetime.

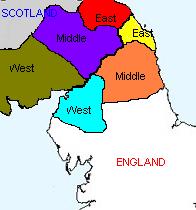

After 1346, the border region was split into East and West marches. Edward III of England wanted peace on the Scottish border while he fought in France. So, the Wardens were given more power to handle legal cases. Their courts worked alongside the common law courts.

Edward III tried to make border law more organized. He appointed supervisors for the Wardens. They made sure that at least two officials were present for court cases. Days of march were planned in advance. People accused of crimes were brought before a mixed English and Scottish jury. If found guilty, they had to pay back victims within 15 days. Sheriffs were also told to help Wardens catch suspects.

During the reign of Richard II of England, there was a lot of raiding. But border law became stronger because powerful families like the Percies and Nevilles in England, and the Douglas family in Scotland, had more influence. For example, the problem of criminals escaping into areas where the King's law didn't reach was partly solved by making a powerful local lord a Warden. By the end of the 1300s, March law was seen as a complete legal system. It worked alongside and improved English common law.

Changes in the 1400s

Under Henry IV of England and Henry V of England, March law was put on hold again as England tried to claim control over Scotland. Also, fights among the border Wardens made things worse. People living on the border suffered greatly from raids, and regular law couldn't help them.

March law came back during the reign of Henry VI of England. A truce in 1424 brought back the border courts. It tried to stop all revenge raids. If raids happened, the offenders had to talk to the Wardens. From then on, serious cross-border crimes were handled in the Warden's courts.

In 1429, new agreements were made that shaped border law for the 1400s. They listed the types of crimes March law would deal with: murder, serious injury, assault, breaking safe travel rules, theft of animals, and illegal grazing. Procedures were set up, like handing over suspects to the Wardens of the other country for punishment. Mixed English and Scottish juries were used. A system for sending criminals back and forth was created. Clerks were present to write down what happened in court. These agreements were the first real attempt to make Anglo-Scottish border law part of international law.

In 1451, March law became more like English court practices. Scottish victims could now take their cases to the English Chancellor if English wrongdoers didn't show up at border courts. The powerful families like the Percies and Nevilles made the Warden courts very busy, often more so than the common law courts.

Edward IV of England kept March law working well. Even when Henry VI of England briefly returned to power, and when James III of Scotland became king, border law continued. In 1473, new rules for cross-border murders were made. They also limited the number of armed followers allowed at the days of march, which often turned into riots. A war from 1480-1484 stopped the border courts, but they were soon brought back by Richard III of England.

In 1484, Richard and James tried to reduce the power of their strong border lords. They separated the Wardens' military duties from the Conservators' job of chasing criminals. This meant that smaller lords who knew the local area well handled the criminal cases.

March Law, 1485-1603

Even with disagreements between Henry VII of England and James IV of Scotland, March law continued to be used. Treaties in 1497 and 1502 included rules for border law. For example, Wardens had to tell their counterparts within ten days if they arrested someone. Those accused of murder would go to a day of march, and if found guilty by a mixed jury, they would be handed over for punishment, often the death penalty.

On the English side, Henry VII changed how Wardenships were held. Royal princes now held the title, and their deputies, who did the actual work, came from less powerful families. This saved money and reduced the power of the great northern lords. This change marked the beginning of the end for the old Warden system.

March law continued under Henry VIII and his children. It was finally stopped when England and Scotland united under one king, James VI of Scotland and I of England, in 1603. James then took strong action against the Border Reivers.

March Law and English Law

March law continued to be used on the Anglo-Scottish border, even when some English kings wanted to get rid of it. This was for several reasons:

- Normal English law was not good at dealing with problems across a border between two different countries. It was hard to get justice from someone who belonged to another nation.

- Constant fighting and raids made it dangerous for judges to travel north to do their jobs.

- The border area had a unique mix of people and loyalties. People often felt more loyal to their local area than to distant governments.

- Kings didn't own much land in the borderlands, so they relied on powerful local lords like the Percies and Douglases. These lords were given special legal power as Warden-Conservators, filling a gap in the law.

Even with these factors, both countries saw March law as an extra layer of law, not a replacement for their own laws. English common law still worked alongside March law throughout this period.

March Law and Scottish Law

Some historians believe that Scottish legal practices had a bigger influence on March law than English law. For example:

- The "hot and cold trod" was a Scottish custom. This allowed people to chase stolen goods across the border, similar to the English "hue and cry."

- Trial by combat (a fight to prove innocence) was still common in Scottish and border practice, even when it was less used in England.

- Mixed English and Scottish juries were more like Scottish legal practices.

- Other Scottish features included using pledges and sureties (promises), paying victims for damages, and seizing property to pay debts.

Days of March: How They Worked

The rules from 1398 said that "days of march" (or "days of truce") should happen every month. However, this rarely happened. Violence among border lords often disrupted the meetings. Later, disagreements between the Wardens could cause long delays.

Meetings were held at various places along the border. Some popular spots included Hadden Stank, Redden Burn, and Lochmaben on the Scottish side. On the English side, places like the Sands in Carlisle, Rockcliffe, and Norham were used.

Once the place and date were set, and safety measures were taken, people would present their complaints. These complaints were then passed to the Warden of the other side. The accused would be called, and those facing punishment would be presented. Cases could be:

- 'Fouled': A guilty verdict.

- 'Cleared': An innocent verdict.

- 'Fouled conditionally': Assumed guilty because the accused didn't show up.

The truce was supposed to last until sunrise the day after the meeting. But sometimes, this didn't happen, leading to more trouble.

March Law: Purpose and Success

Purpose

March law was mainly used to settle disputes. But the days of march also had a political and diplomatic side. They helped prevent small raids from turning into full-scale wars between the two countries. During talks between England and Scotland, border problems were discussed to help smooth over diplomatic issues. This linking of local and national concerns was a deliberate strategy from Edward III's time onwards. The meetings also helped maintain a secret communication channel between the two Crowns.

March law didn't stop all raiding, but it did act as a safety valve. It was most effective during truces and least effective during wars. It was often the only way for victims to get compensation or for criminals to be caught across the border.

Effectiveness

How well March law worked depended a lot on the Wardens and their deputies. Many of them were actually involved with the reivers themselves. For example, a 1563 agreement complained about the "negligence of some officers." Sometimes, frustration led to people taking justice into their own hands, outside of March law. For instance, King James V ordered the hanging of Johnnie Armstrong and his followers without trial in 1530.

While mixed juries were important, cases could also be settled by an "avower." This was a local person from the accused's country who would swear to the truth of the case. A third way was the Warden's oath, where the Warden declared the case was valid. All these methods could be abused. Witnesses or defendants sometimes didn't show up. Wardens tried to balance reparations between Scots and English, meaning smaller cases might not be heard. Intimidation by armed reivers at the meetings was also a problem.

It's hard to know how many victims actually used March law. Another option was a "hot trod," a lawful group of men who could chase stolen property, even across the border, within six days. This was dangerous, as they could be ambushed. A third option was a revenge raid, which was also risky. So, those who used March law might have been people who didn't have enough allies to carry out a trod or a raid.

The fact that more judicial powers were added in the 1500s, when border conditions seemed to get worse, might show that March law wasn't always effective. Sometimes, kings would send armed groups, or Wardens would lead official raids. They even sometimes encouraged reivers to do their own revenge raids, which was against March law.

Given the family ties across the border, the threats to witnesses, the use of blackmail (a word that started in the borderlands), and the involvement of some local lords and Wardens, it's not surprising that March law was often just a "finger in the dyke." It helped, but it couldn't fully stop the problems. Some even argued that these laws actually encouraged the abnormal behavior by recognizing it.

See also

- Anglo-Scottish Wars

- Border Reivers

- March law (Ireland)

- March law (Anglo-Welsh border)

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |