Margaret Frances Sullivan facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Margaret Frances Sullivan

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | Margaret Frances Buchanan 1847 Drumquin, County Tyrone, Ireland |

| Died | December 28, 1903 (aged 55-56) Chicago, Illinois |

| Resting place | Detroit, Michigan |

| Occupation | author, journalist, editor |

| Language | English |

| Alma mater | Academy of the Sacred Heart |

| Spouse |

Alexander Sullivan

(m. 1874) |

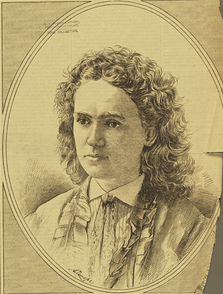

Margaret Frances Sullivan (born 1847 – died 1903) was an amazing writer, journalist, and editor. She was born in Ireland but became famous in America. Margaret wrote for many important magazines. Her articles, called editorials, were so good that they caused national discussions. Even though her name wasn't always on them, people talked about her ideas.

She worked as a main writer for newspapers in Chicago, New York City, and Boston. In 1895, she became the chief editorial writer for the Times-Herald. Later, in 1901, she wrote editorials and art reviews for the Chicago Chronicle.

One of her famous articles explained why there were so few Democrats in the North. Politicians shared it widely. Even after she died, it was reprinted as a perfect example of political writing. Many people thought she was one of the best editorial writers in America. Some even said she was the greatest Chicago had ever seen.

In 1889, Margaret went to Paris as a special reporter for the Associated Press. She covered the Universal Exposition, a big world's fair. She was the only writer given a special seat next to the French president at the opening! This showed how important she was. Margaret knew a lot about art, books, science, politics, music, and money. She could learn any topic quickly because she focused so well. Her book, Ireland of Today, sold 30,000 copies. She also wrote Mexico, Picturesque, Political and Progressive with another author, Mary Elizabeth McGrath Blake.

Contents

Early Life and Schooling

Margaret Frances Buchanan was born in Drumquin, County Tyrone, Ireland, in 1847. She was the ninth child of James Buchanan and Susan Gorman. Her father, who made things in Ireland, died when she was a baby. In 1851, her family moved to Detroit, Michigan, where two of her older siblings already lived.

Margaret went to school in Detroit. She first attended the Academy of the Sacred Heart. There, she became very good at French, which helped her a lot in her newspaper work later. She also went to public schools in Detroit. Her studies focused on classic subjects like Latin and Greek, along with modern languages, music, art, and science. She was a very talented and smart student. Margaret never went to college, but she kept learning by reading and traveling.

Margaret's Career Journey

Starting as a Journalist

After finishing school, Margaret Buchanan became a principal at a public high school in Detroit. In 1870, she moved to Chicago to become a journalist. But it was hard to get a job. Editors told her that being young and a woman was against her. For a while, she didn't have a regular job.

Still, she kept writing stories and sending them to different newspapers. Most of her stories were accepted, but no one offered her a full-time position. Editors just didn't want to hire a woman. Her first accepted story was about a party at the Sacred Heart Convent, where she lived. She took it to the Chicago Times office. The editor quickly looked at it and gave her five dollars. A few days later, he saw her again. He told her the article was "extremely well written" and gave her ten more dollars! Margaret was only 20 years old then.

Because she was new to Chicago and lived a quiet life at the convent, it was hard for her to be a reporter. So, she started writing editorials instead. Editorials are articles that share opinions on important topics. Margaret knew a lot about history, art, science, and politics. She wrote editorials on many different subjects. Even though editors accepted her work, they still wouldn't give her a staff job.

Finally, she went to Wilbur F. Storey, the editor of the Times. She reminded him that he always accepted her editorials and demanded a job. Storey wasn't sure if she really wrote the amazing articles. To test her, he asked her to write about the Canadian money system. Without any hesitation, Margaret wrote a brilliant article. Storey was amazed and offered her a job. "What salary do you expect?" he asked. "The salary of the man whose place I am to take," she replied. This answer showed her confidence. She never let anyone undervalue her work just because she was a woman.

Marriage and Continued Success

In 1874, Margaret married Alexander Sullivan. They had met in Detroit and made their home in Chicago. Alexander became the first president of the Irish National League of America in 1883. This group worked to help Ireland govern itself. Margaret's marriage was happy, and she kept writing editorials. She usually worked from home so it wouldn't interfere with her duties as a wife.

A few years after marrying, Margaret left the Times. She became an editorial writer for the Chicago Tribune. In 1883, she joined the Chicago Herald. The same editors who once refused to hire her now wanted her services! While she wrote on many topics, her political editorials brought her the most fame.

Reporting from Paris

In 1889, Margaret was chosen to represent the Associated Press at the International Exposition in Paris. She was the first woman ever to report for the press at such a big international meeting. When she and her friend tried to get tickets, a French official refused. "But, madam, you are a woman," he said. "Yes, and in monsieur, I expect to find a gentleman," she replied cleverly. The official explained that a woman had never attended such a gathering. Margaret insisted, asking, "Do you not think that Paris should establish a precedent?" Because of her strong will, she and her friend got their tickets.

At the exposition, the President of France tried to give her a less important seat at a big event. Margaret refused, saying she represented the American press. She sent a telegram to James G. Blaine, who was the Secretary of State at the time. Because of her efforts, she was given a place of honor.

Becoming a Chief Editor

During the presidential campaign of 1892, the Chicago Herald asked Margaret to write articles supporting Grover Cleveland. Cleveland's main idea was to change the tariff, which is a tax on goods from other countries. Margaret explained the new tariff so well that Illinois, a state that usually voted Republican, voted Democratic for the first time!

When the Chicago Chronicle newspaper started in 1896, Margaret became its chief editorial writer. She kept this important job until she died. The Chronicle was a Democratic paper, but it disagreed with the idea of bimetallism (using both gold and silver for money). In the election of 1896, the paper supported the Republican idea of using only gold. Margaret was asked to write more campaign articles. She strongly argued against the Democrats' idea of "free silver." Her articles, like "Let the Old Hulk Drift," were used in speeches all over the country.

Helping Her Community

Margaret wasn't part of many women's clubs, but she cared deeply about new ideas and progress. In 1892, she became president of the Women's Educational Society during the World's Fair. She always believed that women could and should be active in public life.

Margaret also led a committee for Catholic Reading Circles in Chicago. These groups helped people learn and discuss ideas. As early as 1879, Margaret taught a small group of students every day. This group was the start of the reading circle idea in Chicago. Her two Reading Circles at the Sacred Heart Institution were very thorough. They were named after important women: the Venerable Mother Barat Circle and the Mother Duchesne Circle.

Personal Life

Margaret was known as a perfect wife. Her home life and public work never clashed. She was very close to Mother Angela Gillespie, who was a director at her school. Margaret admired Mother Angela as both a woman and an educator. In a tribute she wrote, Margaret said Mother Angela believed in a full education for girls. She thought that only partly developing someone was as bad as no development at all.

Margaret was a strong supporter of Irish independence. She loved her home country very much. In 1897, she had a stroke, which affected her health. But she kept writing until she died. In 1903, Margaret had another stroke and passed away on December 28. Her body was taken to Detroit for burial on New Year's Eve.

Published Works

- Ireland of To-day: The Causes and Aims of Irish Agitation, 1881

- Mexico, Picturesque, Political and Progressive, with Mary Elizabeth McGrath Blake, 1888

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |