Martyrs' Day (Panama) facts for kids

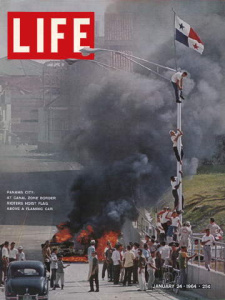

Martyrs' Day (Spanish: Día de los Mártires) is a special day in Panama. It is a day of national sadness that remembers the events of January 9, 1964. On this day, there were big protests against the United States. These protests were about who should control the Panama Canal Zone.

The protests started when a Panamanian flag was torn. Students were also hurt or killed during fights with police and people living in the Canal Zone. This event is also called the Flag Incident or Flag Protests.

U.S. Army soldiers had to step in because the Canal Zone police could not control the crowds. After three days of fighting, about 22 Panamanians and four U.S. soldiers died. This event was a big reason why the U.S. later decided to give control of the Canal Zone to Panama. This happened through the 1977 Torrijos–Carter Treaties.

Contents

Why the Conflict Started

After Panama became independent from Colombia in 1903, the U.S. helped them. But some Panamanians were unhappy because of the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty. This treaty gave the U.S. control of the Panama Canal Zone "forever." The U.S. paid 10 million dollars at first, and then 250 thousand dollars each year.

The U.S. government also bought all the land in the Canal Zone from private owners. The Canal Zone was a strip of land from the Pacific Ocean to the Caribbean Sea. It had its own police, schools, ports, and post offices. It became like U.S. territory, even if not officially.

Many Americans who lived in the Canal Zone were called Zonians. They had lived there for a long time. They ran and kept up the Canal, which was very important. Many Zonians were very proud of their own group and did not like Panamanians. They felt that if the U.S. gave up any control over the Canal Zone, they would lose something important. They were well paid and lived well in this small American area.

In January 1963, U.S. President John F. Kennedy agreed to fly Panama's flag next to the U.S. flag. This would happen at all non-military places in the Canal Zone where the U.S. flag was flown. However, President Kennedy was killed before this plan could happen.

One month after Kennedy's death, the Panama Canal Zone Governor, Robert J. Fleming, Jr., changed the order. The U.S. flag would no longer be flown outside Canal Zone schools, police stations, or post offices. But Panama's flag would not be flown there either. This order made many Zonians very angry. They thought it meant the U.S. was giving up control of the Canal Zone.

Because of this, angry Zonians started flying the U.S. flag everywhere they could. At Balboa High School, school officials took down the first U.S. flag raised there. Then, students walked out of class and raised another flag. They even posted guards to stop it from being removed. Most Zonian adults agreed with the students.

Governor Fleming left for a meeting in Washington, D.C., on the afternoon of January 9, 1964. He and many others thought the U.S.-Panama relationship was very good. But the situation quickly became dangerous while he was still traveling.

What Happened on January 9th

People expected Panamanians to react to the Zonians flying their flags. But the crisis surprised most Americans. Lyndon B. Johnson, who later became president, wrote that he knew there would be trouble when he heard about the students' actions.

News of what happened at Balboa High School reached students at the Instituto Nacional. This was Panama's best public high school. About 150 to 200 students from the institute marched into the Canal Zone. They were led by 17-year-old Guillermo Guevara Paz.

They carried their school's Panamanian flag and a sign saying Panama controlled the Canal Zone. They had told their principal and the Canal Zone police about their plans. Their goal was to raise the Panamanian flag on the flagpole at Balboa High School, next to the U.S. flag.

At Balboa High, the Panamanian students met Canal Zone police. A crowd of Zonian students and adults was also there. After talking, a small group of Panamanian students was allowed to go near the flagpole. The police kept the main group back.

Six Panamanian students, carrying their flag, went to the flagpole. But the Zonians surrounded the flagpole. They sang "The Star-Spangled Banner" and refused the agreement between the police and the Panamanian students. A fight broke out. The Zonian people and police pushed the Panamanians back. During the struggle, Panama's flag was torn.

This flag was important because students had carried it in protests in 1947. Those protests were against a treaty and demanded U.S. military bases leave. Later, people who investigated the events of January 9, 1964, noted that the flag was made of thin silk.

There are different stories about how the flag was torn. Canal Zone Police Captain Gaddis Wall said Americans were not to blame. He claimed the Panamanian students tripped and accidentally tore their own flag. David M. White, a telephone worker, said a student fell, and the old flag tore then. None of these stories have been fully proven.

One of the Panamanian students carrying the flag, Eligio Carranza, said: "They started pushing us and trying to take the flag from us, while insulting us. A policeman used his club, which ripped our flag. The captain tried to take us to where the other Panamanian students were. On the way through the crowd, they pulled and tore our flag."

Even today, people still argue about this event. Both sides say the other started the conflict.

World Reactions and Changes

Many countries around the world did not support the United States. The British and French governments had been criticized by the U.S. for how they handled their colonies. Now, they said the U.S. was being unfair. They argued that the Zonians were just like other colonial settlers.

Egypt's Gamal Abdel Nasser suggested that Panama should take control of the Panama Canal, just as Egypt had taken control of the Suez Canal. Communist governments in the Soviet Union, China, and Cuba strongly criticized the U.S. Even the right-wing Falangist Party in Spain accused the U.S. of attacking Panama.

Importantly, other governments in the Western Hemisphere that usually supported the U.S. did not back them this time. Venezuela led many Latin American countries in criticizing the United States. The Organization of American States (OAS) took over the dispute from the United Nations Security Council. The OAS then sent its Inter-American Peace Committee to investigate.

The committee held an investigation in Panama for a week. To show their unity, all Panamanians stopped working for 15 minutes. Panama wanted the U.S. to be called guilty of aggression, but this did not happen. However, the committee did say that the Americans used too much force.

The President of Panama at the time, Roberto Chiari, ended diplomatic relations with the United States on January 10. On January 15, President Chiari said Panama would not restart relations until the U.S. agreed to talk about a new treaty.

The first steps toward this happened on April 3, 1964. Both countries agreed to restart diplomatic relations right away. The United States also agreed to find ways to "remove the causes of conflict." A few weeks later, Robert B. Anderson, President Johnson's special helper, went to Panama to prepare for future talks. Because of his actions, President Chiari is known as "the president of dignity." The Panamanian ambassador to the United Nations, Miguel Moreno, also gave a strong speech against the United States at the United Nations General Assembly.

This incident was the main reason why the U.S. eventually gave up its "forever" control of the Canal Zone. It also gave up ownership of land there. This happened with the 1977 signing of the Torrijos–Carter Treaties. These treaties ended the Panama Canal Zone in 1979. They also set a time for U.S. military bases to close. Full control of the Panama Canal was given to the Panamanian Government at noon on December 31, 1999.

Remembering the Day

Two monuments have been built in Panama City to remember these events. One was built where the flagpole incident happened. This used to be Balboa High School, but today it is a Panama Canal Authority building. It is named after Ascanio Arosemena, who was the first "martyr" and perhaps the most famous.

The Panama Canal Authority built this monument. It has a covered entrance with a memorial. Each column has the name of a "martyr." In the middle, there is an eternal fire, like the one for U.S. President John F. Kennedy. After that, there is an open "square" with the Panamanian flag on a flagpole.

Another monument is in front of the Legislative Assembly. This was once the border between Panama City and the Canal Zone. It is a life-sized monument shaped like a lamppost. It shows three figures climbing it to raise their flag. This monument is based on a photograph that was on the cover of Life magazine. The photo showed three students climbing a 12-foot safety fence and a lamppost. The one at the top had a Panamanian flag.

See also

In Spanish: Día de los Mártires para niños

In Spanish: Día de los Mártires para niños