Master Juba facts for kids

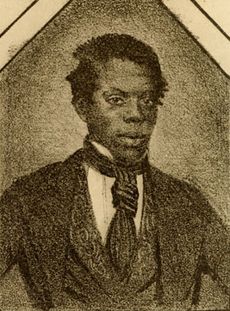

Master Juba (born around 1825 – died around 1852 or 1853) was an African-American dancer. He was very active in the 1840s. He was one of the first black performers in the United States to dance for white audiences. He was also the only black performer of his time to tour with a white minstrel group. His real name was probably William Henry Lane. People also called him "Boz's Juba" after writer Charles Dickens described him in his book American Notes.

As a teenager, Juba started his career in the lively dance halls of Manhattan's Five Points neighborhood. He then joined minstrel shows in the mid-1840s. "Master Juba" often challenged and beat the best white dancers, including a popular dancer named John Diamond. At the peak of his career in America, Juba would imitate famous dancers. He would then finish his act by dancing in his own unique style.

Because he was a black man, Juba performed with minstrel groups. In these shows, he would imitate white minstrel dancers who were pretending to be black. This was called blackface. Even with his success in America, Juba became even more famous in England.

In 1848, "Boz's Juba" traveled to London with the Ethiopian Serenaders. This was a minstrel group made up of white performers. Boz's Juba became very popular in Britain because of his amazing dance style. Critics loved him, and he was the most talked-about performer of the 1848 season. However, some writers treated him like an exhibit. This showed a kind of unfairness. Juba was later seen performing in both Britain and America in the early 1850s. American critics were not as kind to him, and Juba's fame slowly faded. He died in 1852 or 1853. He likely passed away from working too hard and not getting enough food. Historians mostly forgot about him until a 1947 article by Marian Hannah Winter brought his story back to life.

Old documents give different ideas about Juba's dance style. But some things are clear: his dancing made sounds, changed speed, was super fast at times, showed lots of feeling, and was unlike anything people had seen before. His dance probably mixed European folk steps, like the Irish jig, with African steps. These African steps were used by plantation slaves. An example is the walkaround. Before Juba, blackface performances showed black culture more truly through dance than in other ways. But as blackface performers copied parts of Juba's style, he made this even more real. Juba greatly influenced the development of American dance styles like tap, jazz, and step dancing.

Contents

Early Life and Dance Career

We don't know much about Juba's early life. There are only a few details in old records. Other stories written years after he died might not be fully true. Dance historian Marian Hannah Winter thought Juba was born to free parents in 1825 or later. Showman Michael B. Leavitt wrote in 1912 that Juba was from Providence, Rhode Island. Theater historian T. Allston Brown said his real name was William Henry Lane.

According to a newspaper from 1895, Juba lived in New York's Five Points District. This area had Irish immigrants and free black people living together. There were dance houses and saloons where black people often danced. The Irish and black communities shared parts of their cultures, including dance. The Irish jig mixed with black folk steps. In this place, Juba learned to dance from others. One of his teachers was "Uncle" Jim Lowe, a black jig and reel dancer. By the early 1840s, Juba was dancing for food and money. Winter thought that by age 15, Juba might not have had a family.

Old records show that Juba performed in dance contests, minstrel shows, and variety theaters. This was in the Northeastern United States starting in the mid-1840s. His stage name Juba probably came from the juba dance. This dance was named after an African word, giouba. "Jube" and "Juba" were common names for slaves who were good at dancing or music. It's a bit confusing because at least two black dancers used the name Juba back then.

An old letter from 1841 or 1842 said that Juba worked for showman P. T. Barnum. The writer claimed Barnum had managed Juba since 1840. Barnum supposedly dressed Juba as a white minstrel performer by putting blackface makeup on him. He then had him perform at the New York Vauxhall Gardens. In 1841, the letter said Barnum even presented Juba as the famous Irish-American dancer John Diamond.

Dance Challenges and Fame

In the early 1840s, Juba started doing dance competitions called challenge dances. He competed against his white rival, John Diamond. Diamond advertised that he could "delineate the Ethiopian character superior to any other white person." People disagree about when their first contest happened. It might have been when Diamond worked for Barnum or a year or two later. An advertisement from 1844 shows how these matches were promoted:

Historian James W. Cook thinks Juba and Diamond might have planned their first competition. This would have been a way for both of them to get publicity. It was very unusual for a black dancer to claim to be better than a famous white dancer. This was especially true in New York City and the country in the mid-1840s.

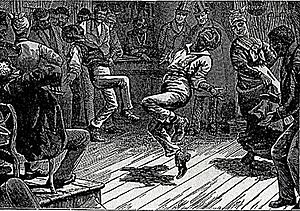

Challenge dances usually had three judges. One judge sat on the stage and counted the beat. Another sat near the orchestra and judged the style. The third judge went under the stage to listen for "missing taps, defective rolls and heel work." After the dance, they compared notes and picked a winner. Audience members and friends of the dancers would bet on who would win. If the judges couldn't decide, the crowd could choose the winner. Records show that Juba beat Diamond in all but one competition.

An old paper from the Harvard Theatre Collection describes the one dance competition Diamond won. A fan of minstrel shows wrote about it. "One of the fiddlers played a reel for him [Juba], and he shuffled, and twisted, and walked around, and danced on for one hour and fifteen minutes by the watch." Then Juba made a loud sound with his left foot as the crowd cheered. He got a drink from the bar. Diamond went next. He tried to act calm but determined. He knew losing would upset Barnum, and his race was at stake. "There was another thing about this match-dance that made Diamond want to win. You see it was not only a case of Barnum's Museum against Pete Williams's dance-house, but it was a case of white against black. So Jack Diamond went at his dancin' with double energy—first, for his place, next, for his color." He danced longer than Juba and "gave a hop, skip and a jump, a yell and a bow." Their most famous match was in New York City in 1844. Juba won $500. Juba then went to Boston, calling himself the "King of All the Dancers." He performed there for two weeks.

In 1842, English writer Charles Dickens visited New York's Five Points. This was around the time of the challenge dances. Dickens might have heard rumors about Barnum dressing up a black boy as a white minstrel. There, Dickens saw a "lively young negro" perform. A newspaper later said this dancer was Juba.

Juba may have used the free publicity from Dickens to move from saloons to the main stage. In one show, Juba imitated white minstrel performers like Richard Pelham and John Diamond. The idea that Juba could "imitate himself" after copying his rivals showed how white people were taking over black culture. However, Juba's imitations of his white rivals proved he was better at the popular blackface dance styles. They also showed that this was a true art form. James W. Cook wrote that "the Imitation Dance served as a powerful act of defiance."

Dancers began to see Juba as the best, and his fame grew quickly. By 1845, he was so well known that he no longer had to pretend to be a white minstrel on stage. He toured New England with the Georgia Champion Minstrels in 1844. The show bill called him "The Wonder of the World Juba, Acknowledged to be the Greatest Dancer in the World." It said he had danced against John Diamond for $500 and proved himself the "King of All Dancers." The bill added, "No conception can be formed of the variety of beautiful and intricate steps exhibited by him with ease. You must see to believe."

In 1845, Juba started touring with the Ethiopian Minstrels. This group gave him top billing over its four white members. This was unheard of for a black performer. From 1846, Juba toured with White's Serenaders as a dancer and tambourine player. He worked with them on and off until at least 1850. He played a character named Ikey Vanjacklen, "the barber's boy." This was in a show called "Going for the Cup, or, Old Mrs. Williams's Dance." It was one of the earliest known minstrel plays. The story focused on Juba's dancing in a setting of competition. The plot involved two characters trying to rig a dance contest. They would soap the floor so everyone but Ikey would fall. They bet on Vanjacklen, but in the end, the judge stole the money.

England Tour in 1848

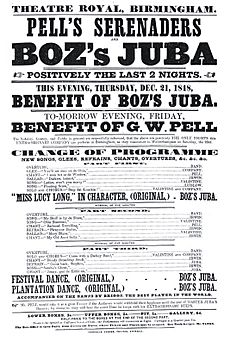

In 1848, a dancer called "Boz's Juba" performed in London, England. He was part of the Ethiopian Serenaders. This was a blackface minstrel group led by Gilbert W. Pell. The company had performed in England two years before. They had made minstrelsy popular with middle-class British audiences by being more refined. With Boz's Juba, the group toured theaters and lecture halls in Britain for the next 18 months.

It's not completely clear who "Boz's Juba" was. "Boz" was a pen name used by Dickens. The Ethiopian Serenaders used quotes from Dickens's American Notes in their ads. The Illustrated London News thought the black dancer was the same person Dickens had seen in New York in 1842. Dickens never said this was wrong. However, the Serenaders' claims were for advertising. Dickens might not have remembered the exact details of the dancer he saw in Five Points. Writers from that time and later generally agreed that Boz's Juba was the same person Dickens had seen and who had danced against Diamond.

Boz's Juba seemed to be a full member of Pell's group. He wore blackface makeup and played Mr. Tambo, the tambourine player. He performed opposite Pell, who played Mr. Bones (on the bone castanets). He sang popular minstrel songs and performed in short plays. Even though he was part of the group, ads for the troupe highlighted Juba's name separately. The Serenaders continued touring Britain and played at places like the Vauxhall Gardens. The tour ended in 1850. Their 18-month tour was the longest minstrel tour in Britain at that time. Juba and Pell then joined a group led by Pell's brother, Richard Pelham. The company was renamed G. W. Pell's Serenaders.

Juba was the most written-about performer in London during the summer of 1848. This was a big achievement, as there were many performers. Critics loved him, giving him praise usually given to popular ballet dancers. In August, Theatrical Times wrote, "The performances of this young man are far above the common performances of the mountebanks who give imitations of American and Negro character; there is an ideality in what he does that makes his efforts at once grotesque and poetical, without losing sight of the reality of representation."

Master Juba's time with Pell makes him the earliest known black performer to tour with a white minstrel group. Experts have different ideas about why he was allowed to do this. Dance historian Marian Hannah Winter believes Juba was simply too talented to be held back. Dance historian Stephen Johnson thinks Juba's talent was less important. He points to the idea of Juba being seen as something exotic or a display. During the same time, London had exhibits of Arab families, Bushmen, Kaffir Zulus, and Ojibwa warriors.

Pell's advertising often said that Juba's dance was real and true to his culture. Reviewers seemed to believe this. A critic in Manchester said that Juba's dances "illustrated the dances of his own simple people on festive occasions."

Later Life and Passing

Back in the United States, Juba performed alone in music halls and theaters in New York. He had gone from being unknown to famous, and then back again. American critics were not as kind as the English ones. A reviewer wrote in 1850 that Juba was "jumping very fast... but too fast is worse than too slow." Another paper wrote in 1850, "The performances of Boz's Juba have created quite a sensation in the gallery, who greeted his marvellous feats of dancing with thunders of applause... In all the rougher and less refined departments of his art, Juba is a perfect master."

The last known record of Juba is from September 1851. It places him at the City Tavern in Dublin, Ireland. It says, "Boz's Juba appears here nightly and is well received." A performer known as Jumbo reportedly died two weeks later in Dublin. Dance historian Marian Hannah Winter said that Juba died in 1852 in London. More than 30 years later, theater historian T. Allston Brown wrote that Juba "married too late (and a white woman besides), and died early and miserably." He would have been in his late 20s.

In January 1854, an English newspaper advertised a show in Liverpool. It featured "the celebrated Boz's Juba, immortalised by Charles Dickens." On February 3, 1854, a death was recorded in Liverpool for a man named "Bois Juba." The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography believes "Bois Juba" was a mistake for "Boz's Juba." Other details on the death certificate, like being an American-born musician aged 30, match Juba. "Bois Juba" died in the infirmary in Liverpool and was buried on February 6, 1854. The exact spot of his grave is not known today.

The reason for Juba's death is not certain. Winter suggested his "almost superhuman schedule" and how he "burned up his energies and health" were the causes. If all the "Jubas" were the same person, records show Juba worked day and night for 11 years. Especially when he was young, Juba worked for food. He would have eaten simple tavern meals. Such a demanding schedule, with poor food and little sleep, likely led to his early death.

Performance Style

Playbills give us a general idea of what Juba did in his shows. No one of his own race, class, or job wrote about his dancing at the time. He was clearly an amazing dancer. But it's hard to know exactly how he danced or how different he was from other black dancers who are now forgotten. The descriptions don't have clear comparisons. The most detailed accounts come from British critics. Juba must have been more new and exciting to them than to Americans. These writers were writing for white, middle-class British audiences. Other descriptions came from ads, so they might not be completely fair. Juba was called a "jig dancer." At that time, "jig" meant Irish folk dancing. But it was starting to include black dance. The Irish jig was common then. So, Juba's great skill and new ideas might explain why he got so much attention.

These accounts give unclear descriptions of his dance moves. While they often try to be very detailed, they also disagree with each other. Some try to be very exact, while others say Juba's style was impossible to describe. But the reviews do agree on some things. Juba's dance was new and hard to describe. It was wild, changed speed and mood, was well-timed, made sounds, and showed lots of feeling.

He was a key member of the groups he toured with. This is clear from the roles he played in the minstrel show by Pell's Ethiopian Serenaders. Juba did three dances in two ways. He performed "festival" and "plantation" dances in fancy clothes with Thomas F. Briggs on banjo. He also dressed in drag to play Lucy Long in the song of that name, sung by Pell.

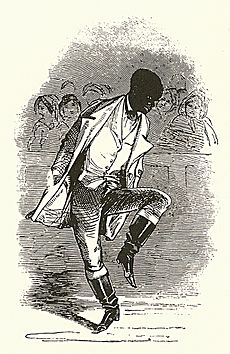

Old pictures of Juba give more clues. Two drawings from a review of Juba at the Vauxhall Gardens show a man copying Juba's dance. He seems to be doing a cake-walk, with his leg kicked high and his hat in his hand. A cartoon of Juba shows him with bent knees and spread legs. One leg looks ready to hit the floor hard, and his arms are close to his body. The most common picture of Juba, from 1848, shows him in a similar pose, with his hands in his pockets. One British account from 1848 has a picture that shows Juba doing what looks like a jig.

Hard to Describe

Writers found it hard to describe Juba's dancing. A reviewer wrote that "[t]he effort baffles description. It is certainly original, and unlike anything we have ever seen before." Another wrote of "a series of steps, which altogether baffle description, from their number, oddity, and the rapidity with which they were executed." Writers tried to compare Juba's steps to dances British audiences knew.

However, these comparisons might not truly show Juba's personal style. As a blackface minstrel, Juba might have copied these dances in a funny way. He also made funny faces while he danced. Charles Dickens wrote that the young black dancer in New York "never leaves off making queer faces."

Unique and Changing

Juba seemed to dance in different styles and at different speeds in one show. Confused reviewers struggled to explain how he moved each part of his body on its own. They also wondered how he kept changing his rhythm and mood. A critic wrote, "Now he languishes, now burns, now love seems to sway his motions, and anon rage seems to impel his steps." A London audience member wondered, "How could he tie his legs into such knots, and fling them about so recklessly, or make his feet twinkle until you lose sight of them altogether in his energy." The Mirror and United Kingdom Magazine said his dancing had "such mobility of muscles, such flexibility of joints, such boundings, such slidings, such gyrations, such toes and such heelings, such backwardings and forwardings, such posturings, such firmness of foot, such elasticity of tendon, such mutation of movement, such vigour, such variety, such natural grace, such powers of endurance, such potency of pastern."

Sound and Rhythm

The sounds Juba made with his feet were another thing that made his dance special. Reviewers often talked about these sounds. Playbills asked audiences to be quiet during Juba's dances so they could hear the rhythm of his steps. The Manchester Guardian said, "To us, the most interesting part of the performance was the exact time, which, even in the most complicated and difficult steps, the dancer kept to the music." An old paper from 1848 said, "... the dancing of Juba exceeded anything ever witnessed in Europe. The style as well as the execution is unlike anything ever seen in this country. The manner in which he beats time with his feet, and the extraordinary command he possesses over them, can only be believed by those who have been present at his exhibition." A critic in Liverpool compared his steps to Pell playing the bones and Briggs playing the banjo. The Morning Post wrote, "He trills, he shakes, he screams, he laughs, as though by the very genius of African melody." Descriptions also show parts of the hand jive in his dance.

Juba also laughed very quickly during his dances, matching the rhythm of his steps.

Realness

Juba's dance definitely included parts of real black culture. But how much is not fully known. Parts of Juba's style are common in black dance. These include making sounds, changing rhythms, using the body as an instrument, changing mood and speed, big movements, and focusing on solo dancing. Juba may have shown Africa's cool aesthetic: being calm and full of life.

Historians think British critics couldn't describe Juba's style because he used African-based forms they didn't know. White accounts of his shows sound like descriptions of slave dances from the Caribbean and the United States. Juba followed the traditions of free black people in the North. Johnson has found proof that Juba was doing "a quite specific, African-infused plantation dance." Descriptions of his dance suggest Juba performed black steps like the walk-around, the pigeon wing, an early Charleston, the long-bow J, trucking, the turkey trot, and tracking upon the heel. However, Johnson warns that "I might see any number of dance steps here, if I look longingly enough."

Juba was in a white-dominated field, performing for mostly white audiences. He probably changed his culture's music and dance to succeed in show business. This was true for his comedy acts and songs, which were like typical minstrel shows. One observer in London in the 1840s saw slave dances on a plantation. He called them "poor shufflings compared to the pedal inspirations of Juba." Juba's dance might have been a mix of African and European styles. Dickens's writing about the New York dancer only describes leg movements, which points to the Irish jig. But he also says Juba did the single and double shuffle, which are black-derived steps. Historians Shane and Graham White have said that black people of this time performed European steps in a different style than white people. Historian Robert Toll wrote that Juba "had learned a European dance, blended it with African tradition, and produced a new form, an Afro-American dance that had a great impact on minstrelsy." Dance historians Marshall and Jean Stearns agreed. They said that with William Henry Lane, the mix of British folk and American black dance in the United States led to something new by 1848. So, people from other countries who saw it thought it was a new creation.

Legacy and History

The terms juba dancer and juba dancing became common in theaters after Master Juba made them popular. Actors, minstrels, and British clowns were inspired by Juba. They adopted blackface and performed dances like Juba's as a stage character called the "Gay Negro Boy." This character spread to France and Belgium when British circuses toured there. Parts of these dances were still seen among British whiteface clowns as late as the 1940s. Juba's great success in Manchester might have shown that the city would later become a dance center in the United Kingdom. However, Juba also made white audiences think of black people as naturally musical, which was a harmful idea.

While the name Juba became part of dance history, the man himself was forgotten for many decades. William Henry Lane is seen as a leader in blackface minstrel entertainment. He passed away in 1854 in Liverpool. For over 90 years after his death, Juba was mostly forgotten by dancers and historians. He only appeared in short mentions in books about minstrelsy. Stephen Johnson has suggested that white entertainers and historians might have purposely played down Juba's importance. Or, perhaps Juba was simply not that influential. Even black historians ignored Juba until the mid-20th century. They preferred to focus on Ira Aldridge, an African American actor who became famous in Europe.

In 1947, dance historian Marian Hannah Winter started to bring Juba's story back. She wrote an article called "Juba and American Minstrelsy." Winter said Juba overcame challenges of race and class to become a successful dancer. Winter was the first to write that Juba brought parts of African dance into Western dance. She said he helped create a unique American dance style. In doing so, Winter believed Juba took back elements that had been taken from African Americans in the racist culture of the 1800s. She also said he invented tap dancing. In short, Winter "made [Juba] significant."

When Winter wrote her article, there wasn't much study on African American history, dance history, or minstrelsy. Winter based her article on only a few sources. Still, later writers have mostly agreed with her ideas. As recently as 1997, music expert Dale Cockrell wrote that "The best treatment of Juba, though it is shot through with errors, is still Winter 1948." Winter's idea that Juba was the "most influential single performer of nineteenth-century American dance" is now widely accepted. His career shows that black and white people did work together to some extent in blackface minstrelsy.

In recent years, scholars have often pointed to Juba as the start of tap dancing and, by extension, step dancing. Winter wrote that "The repertoire of any current tap-dancer contains elements which were established theatrically by him." Dancer Mark Knowles has agreed, calling Juba "America's first real tap dancer." Music historian Eileen Southern calls him the "principal black professional minstrel of the antebellum period (and) a link between the white world and authentic black source material." Scholars say Juba was the first African American to add parts of real black culture into American dance and theater. By doing this, Juba made sure that blackface dance was more truly African than other parts of the minstrel show. Johnson, however, has warned against this idea. His look at the old records shows more unique and unusual things in Juba's dance than early tap or jazz.

See also

In Spanish: Master Juba para niños

In Spanish: Master Juba para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |