Milicianas in the Spanish Civil War facts for kids

Milicianas were brave women who fought in the Spanish Civil War. They came from a time when women were starting to get more involved in politics and workers' groups. Before the war, women protested and rioted, even though male leaders sometimes ignored them.

When the Second Spanish Republic was formed, it gave women more rights. They could vote, get divorced, go to school, and even run for elections. These new freedoms encouraged many women to join the fight when the war began.

In 1934, women helped striking miners in Asturias. This made some people on the right side of politics worried that women would take up arms. Two years later, the Spanish Civil War started. Women quickly joined the fight to defend the Republic. Over 1,000 women joined militias and fought on the front lines. Unlike men, these women chose to fight. Many were Communists or Anarchists. Some women from other countries also came to Spain to fight.

On the front lines, women fought alongside men in mixed groups. They were brave, but some male leaders still made them do support jobs. Many women were injured or killed. The first Spanish Republican woman to die in battle was Lina Ódena on September 13, 1936. Women fought from July 1936 until March 1937, when they were officially told to leave the front. Male leaders made this decision, and the women did not agree with it.

The important actions of these women fighters have often been overlooked.

Contents

Women Before the War (1800 - 1930)

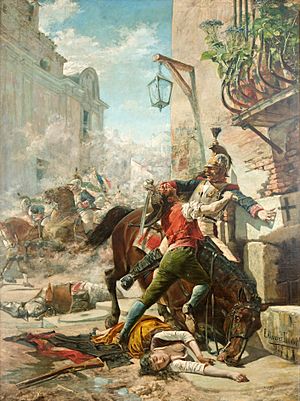

Early Fighters in Spain

Before the Second Republic, there were no large groups of women fighting in Spain. But some famous women did take part in battles. For example, Agustina de Aragón, Manuela Malasaña, and Clara del Rey fought against Napoleon's army during the Peninsular War (1808-1814). A newspaper even wrote that women in Madrid were braver than men during that war. These women were seen as heroes, but they were unusual for their time.

During this period, women were mostly kept out of politics. They formed helper groups to join political movements like socialism and anarchism. Anarchist women later went to the front lines in larger numbers during the Civil War because they had been more directly involved in politics.

Women in the Primo de Rivera Dictatorship (1923-1930)

During the Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera, women started protesting more in the streets. Even though left-wing male leaders often ignored them, women became more aware of their need to be active in society. They joined riots and protests to improve their lives. However, they did not yet take up weapons against the government.

In 1930, Spain's king left his throne, ending the dictatorship. This led to the start of the Second Republic.

The Second Spanish Republic (1931 - 1937)

New Rights for Women

The Second Spanish Republic gave women many new rights. These rights encouraged women to become more active in society and later helped them decide to go to the front lines. The new constitution gave women the right to vote and to run for office. They could also get jobs in government and go to school at all levels. Divorce also became legal. In the first elections, three women were elected to office even before women could vote!

Many women's political groups were created across Spain during the Second Republic. The Committee of Women against War and Fascism was formed in 1933. It was supported by the Communist Party of Spain and Dolores Ibárruri. This group quickly attracted women from different political backgrounds.

Mujeres Libres

Some anarchist women felt left out by male leaders. This led to the creation of Mujeres Libres (Free Women) in May 1936. This group was started by Lucía Sánchez Saornil, Mercedes Comaposada, and Amparo Poch y Gascón. Their goal was to free women from "enslavement to ignorance, enslavement as women, and enslavement as workers." Many women who later became milicianas learned about fighting through anarchist groups during this time.

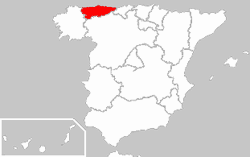

The Asturian Miners' Strike (1934)

Women played important roles in the Asturian miners' strike of 1934. This was one of the first big conflicts of the Second Republic. Workers' militias took control of mines in Asturias. Some women helped with propaganda, others helped the miners, and some even fought. After the government stopped the uprising, many people were jailed, including a large number of women.

During the fighting in Oviedo, women helped in many ways. Some cared for the wounded while bombs fell. Others picked up weapons. Still others brought food and encouraging words to fighters. Aída Lafuente was a Spanish woman who fought in Asturias in October 1934.

The Asturian conflict made some people on the right side of politics worried that women would try to take power. Both sides saw these women as heroes, but men wanted to limit their political actions. Women also built barricades, fixed clothes, and joined street protests. For many, this was their first time being involved without a male family member. Aída Lafuente died during this conflict.

The Spanish Civil War (1936 - 1939)

War Begins

On July 17, 1936, a military group tried to take over Spain. They thought it would be an easy win, but they were wrong. People loved the Second Republic and fought back. This led to a divided Spain and the long Spanish Civil War, which lasted until April 1, 1939.

The military group, led by Francisco Franco, had support from Italy and Germany. The Republican side included Socialists, Communists, and other left-wing groups.

When the revolt was announced, people immediately went into the streets. Dolores Ibárruri famously said, "It is better to die on your feet than live on your knees. ¡No pasarán!" (They shall not pass!).

Women Join the Fight

When the war started, women had two choices: fight on the front lines or help in support roles behind the front. Their options were not limited like women in World War I, who mostly had support roles.

The group Agrupación de Mujeres Antifascistas played a big part in sending women to the front. About 1,000 Spanish women volunteered to fight on the Republican side shortly after the war began. Many armed women helped defend Madrid. This quick action by women helped stop the military from winning easily, making the war last longer.

Most militias were formed by groups like trade unions and political parties. Unions like CNT and UGT helped these militias with supplies. Women were not asked to join; they actively sought out places to enlist. Unlike men, women chose to fight. It was often hard for them, as many militias did not want women, and women constantly had to prove themselves.

Other women, like Dolores Ibárruri, encouraged women to fight. In Madrid, many women were armed to defend the city. About 1,000 women fought on the front lines, while thousands more defended cities. Madrid even had a women-only battalion.

Communist and anarchist groups attracted the most women fighters. The Socialist Party (PSOE) was one of the few groups that did not want women in combat. They believed women should be heroes at home. Women who were Socialists and wanted to fight joined communist or socialist youth groups.

Women also came from other countries to fight in the International Brigades. Between 400 and 700 women came from places like the United States, France, and Germany. They often worked as nurses or doctors. Some Jewish, Polish, and American women did fight in combat, but they were often discouraged.

The first Spanish Republican woman to die in battle was Lina Ódena on September 13, 1936.

Life on the Front Lines

On the front, women usually served in mixed-gender units. They moved around Spain as needed. Women in defense groups behind the lines were more likely to be in women-only battalions.

Women on the front often had to fight and also do support jobs. Male leaders sometimes made them do traditional tasks like cooking and cleaning, even though they were also fighting. Despite this, their bravery was recognized by their comrades.

Most women on the front were part of militias linked to political groups. Very few were in the regular Republican army. In the first few months, the Fifth Regiment had the most women fighters. Most leaders of communist, anarchist, or POUM groups gave women equal roles in combat. However, women were often expected to care for injured comrades, which sometimes put them in more danger. Some women were shot while helping others.

Some women were told they could only stay on the front if they worked as nurses or taught illiterate men to read. Many of these women left to find units where they could fight. Most women in the International Brigades worked as nurses or doctors.

Women proved they could handle many different combat roles. Women in defense battalions practiced with weapons and marched daily. Many also learned to use machine guns. POUM was the only group that trained women with weapons. The lack of training for women in other militias was later used as an excuse to remove them from the front.

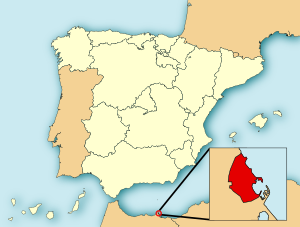

Milicianas came from all over Spain, including Madrid, Majorca, Catalonia, and Asturias. One woman even became a captain of an artillery company.

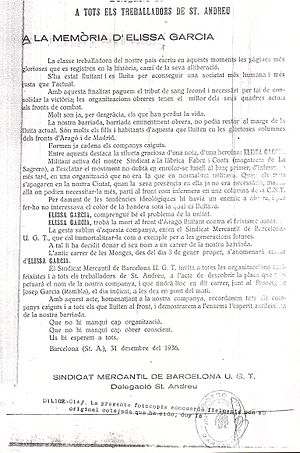

These women came from different left-wing political groups. María Elisa García was a socialist miliciana who fought with the Popular Militias.

Women were injured on the front. Rosario Sánchez Mora lost her hand in an explosion. Jacinta Pérez was badly wounded but told her comrades to keep fighting.

Some women in the Pasionaria Column often tried to leave because their leaders tried to keep them out of combat. Instead, they were made to cook and clean.

Some milicianas cut their hair short in case they were captured. They did not want their heads shaved by Nationalists and paraded around. Franco, the Nationalist leader, sometimes ordered the execution of captured Republican women fighters, even shocking his German allies.

In late 1936, milicianas were seen as equals by many male fighters. They were motivated by their revolutionary beliefs and wanted to change society. A few women fought because their family members were fighting, but most fought for their beliefs.

Some people saw women fighters as unnatural. They became suspicious of women on the battlefield, thinking they might be spies. This fear later led to women being removed from the front. This, along with the lack of weapons training, was used as a reason to remove them.

Many milicianas, like Lina Ódena, Soledad Casilda Méndez, and Rosario Sánchez Mora, became heroes of the Republic.

Key Battles and Moments

July 1936

- Aragon Front: Catalan militias, including a small group of elite women fighters, moved to the Aragon front. Concha Pérez Collado joined a column and went to Azaila. Soledad Casilda Méndez was one of only two women fighting in her Basque militia.

- Barcelona Front: The Unión de Muchachas battalion had 2,000 women aged 14 to 25. They started training in July 1936. These women were athletes who had protested the 1936 Olympics and joined the Republic when the war started. This included English woman Felicia Browne and Swiss woman Clara Thalmann.

- Siege of Cuartel de la Montaña: Women-only battalions helped defend cities. Barcelona had one, Mallorca had the Rosa Luxemburg Battalion, and Madrid had the Unión de Muchachas. Trinidad Revoltó Cervelló fought on the front lines in Barcelona. Angelina Martínez fought bravely at the Montaña Barracks attack, even after most of her unit was killed.

- Madrid Front: POUM initially required both men and women to fight and do support roles. Captain Fernando Saavedra said these women fought just like men. Fidela Fernández de Velasco Pérez was trained with weapons before the war and fought outside Madrid. She even captured a cannon. Rosario Sánchez Mora was one of the first women to join the militias in Madrid at age 17. Teófila Madroñal joined the Leningrad Battalion and fought during the Siege of Madrid. Margarita Ribalta joined a Communist column and led an advance group, carrying a machine gun. Argentine Mika Feldman de Etchebéhère joined a POUM militia and fought near Madrid.

August 1936

Women helped defend Barcelona from behind the lines.

- Battle of Majorca: POUM had a column with women fighters in the Mallorca campaign. Trinidad Revoltó Cervelló fought on the front lines there. Catalans sent 30 women fighters to the Balearic Islands. The Rosa Luxemburg Battalion also fought in Mallorca.

- Aragon Front: Felicia Browne, an English artist, died on the Aragon front on August 25, 1936. She was the first British volunteer to die in the war. Clara Thalmann also served on the Aragon Front. Concha Pérez Collado's unit fought in Azaila and later at Belchite. Pepita Laguarda Batet and her boyfriend joined the Ascaso Column and fought on the Aragon front.

September 1936

- Aragon Front: Pepita Laguarda Batet was badly wounded and died on September 1, 1936, while fighting near Huesca.

- Sierra Front: In September 1936, the Largo Caballero Battalion, which included about ten women, fought on the Sierra front.

- Madrid Front: By September, Mika Feldman de Etchebéhère became a commander after her own commander was killed.

October 1936

- Zaragoza Front: Many women in the International Group of the Durruti Column died fighting in October 1936 at Perdiguera.

- Siege of Sigüenza: Women fighters and civilians were trapped for four days at the Sigüenza Cathedral during a Nationalist siege. POUM Captain Mika Feldman de Etchebéhère was among those who survived. Her bravery earned her a promotion.

November 1936

- Siege of Madrid: The Women's Battalion, organized by the Communist Party, fought only with women on the Madrid front. Some nurses from the Fifth Regiment joined this battalion. Communist women could become leaders on the front. 22-year-old Aurora Arnáiz commanded a JSU column. Julia Manzanal became a Political Commissar at age 17 and fought on the front lines. The Unión de Muchachas, a communist women's battalion, fought on the front lines starting November 8, 1936.

December 1936

The Republican government tried to turn militias into formal army units. Until then, women had joined militias linked to political parties and unions.

- Tardienta Sector: Concha Pérez Collado and other milicianas fought in the Tardienta sector. They were moved off the front by the end of the year.

January 1937

- Battle of Jarama: In January 1937, at the Battle of Jarama, three Spanish milicianas inspired men to hold their ground. They refused to retreat from their machine gun post.

March 1937

- Madrid Front: Salaria Kea, the only African American woman in the International Brigades, joined as a nurse. She was captured by the Nationalist army but escaped six weeks later. POUM milicianas in Madrid were told by Communist groups that they could not fight. They were instead made to cook and do laundry for the men.

May 1937

- Vizcaya Front: María Elisa García was killed in combat in the mountains on May 9, 1937.

- Barcelona Front: Concha Pérez Collado was ambushed and wounded in Barcelona while patrolling.

- May Days: Clara Thalmann fought in the Barcelona May Days conflict. She met George Orwell on the barricades. After a crackdown, she was jailed but later returned to Switzerland. Teresa Rebull, a POUM nurse, also faced punishment and fled Spain.

June 1937

- Huesca Offensive: Women continued to die in combat. Margaret Zimbal was shot by a sniper while helping an injured comrade.

- May Day Fallout: Many milicianas in Barcelona tried to leave the city after being freed from prison due to the May Days events.

September 1937

- Republican Army Attacks: Foreign observers often wrote about women's bravery. In September 1937, at Cerro Muriano, Republican forces fled, but a small militia with two women held strong against Nationalist bombs.

October 1937

- Northern Front: Argentina García fought on the front in October 1937. Her bravery earned her a promotion to Captain.

July 1938

- Battle of the Ebro: Salaria Kea, serving as a nurse, was with the Abraham Lincoln Battalion during the Ebro Offensive.

Women Leave the Front

Historians disagree on the exact date women were told to leave the front lines. Some say it was late 1936, others say March 1937. It's likely that different leaders made their own decisions, so women gradually left the front. By September 1936, women were already being encouraged to leave.

In Guadalajara, women were told to leave the front in March 1937. Most were moved to support roles behind the lines. A few refused to leave, and their fate is unknown. Some women who left the front joined women's groups defending cities like Madrid and Barcelona. When Juan Negrín became the head of the Republican army in May 1937, women's time in combat ended. He also stopped foreign groups from sending women fighters.

Feminist groups changed their message, suggesting women should help on the home front or had different roles than men in war.

The decision to remove milicianas from the front was made by male Republican leaders. The women on the front did not agree. They saw it as a step backward, returning to old roles. They felt it was part of a bigger problem for women in society. Neither the milicianas nor the men they fought with protested their removal. The women were upset that their male comrades did not support them. So, the milicianas quietly left the front without public protest.

Removing women from the front was part of a plan to make the Republic more appealing to conservative people. These conservatives wanted to keep traditional Spanish beliefs about women's roles. This decision, based on ideas like women not knowing how to use weapons, actually encouraged Nationalist ideas.

How Media Showed Women Fighters

Republican propaganda showed women in different ways: as symbols of the fight, as caring nurses, as victims, as representatives of the Republic, as protectors of the home front, and as fighters.

The miliciana was an important symbol for the Republican side between July and December 1936.

Both Spanish and foreign media showed these women fighters breaking traditional gender roles. At first, this was a problem for some people in Spain, as the country had very traditional ideas about gender. While Republicans became more accepting, this changed by December 1936. The government started using the slogan, "Men to the Front, Women to the Home Front." By March 1937, this idea spread, and women were removed from combat roles.

In contrast, Nationalist propaganda showed the "mujer castiza" (traditional woman). She was modest, pure, and self-sacrificing. She supported the Spanish family by working at home and would never fight.

Milicianas on the front often wrote about their experiences for party newspapers. They often wrote about inequality, like having to fight and also do support jobs while men rested.

After women were removed from the front, they stopped appearing in Republican propaganda. They went back to being shown in their traditional roles at home. Stories about POUM fighters became more known because they often published their memories or had better connections with international media.

In the end, milicianas in propaganda often became a symbol of a gender ideal. Their images were often made for men on both sides of the war.

After the War (1938 - 1973)

Life Under Franco

When the Civil War ended and Francoist Spain won, traditional gender roles returned. Women were not allowed to serve in combat. After the war, many milicianas faced difficulties. They were mocked by propaganda, and the new government tried to imprison or torture them. Many fighters could not read or write, which limited their opportunities later. Those who went into exile in France also faced restrictions. Women who stayed politically active faced sexism in Communist and anarchist groups.

Some women veterans continued to fight against the state in secret. They used tactics like bombing police stations, robbing banks, and attacking offices. Women involved in this resistance included Victoria Pujolar, Adelaida Abarca, and Angelita Ramis. They helped connect exiled leaders with people in Spain and planned attacks.

Their Stories Ignored

The important contributions of Spanish women who fought for the Republic have often been ignored. One big reason was the sexism at the time. Women's issues were not seen as important, especially by the winning Francoist side. When women's involvement was discussed, it was treated as small stories, not part of the main history of the war. Since the Nationalists won, they wrote the history. They wanted to bring back traditional gender roles, so they had even less reason to talk about women fighting on the losing side.

Francoist propaganda actively made fun of milicianas. Many were imprisoned or tortured, even decades after the war. Because of this, many women who fought were forced to stay silent. The first time Spain's milicianas were openly discussed was in 1989 at a conference about the Civil War.

Another reason their role has been ignored is a lack of original documents. Sometimes, governments destroyed documents, or women themselves destroyed them to protect themselves. Hiding their involvement often saved their lives. In other cases, battles destroyed important documents about women's roles on the front.

See also

In Spanish: Milicianas en la guerra civil española para niños

In Spanish: Milicianas en la guerra civil española para niños

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |