Museum of the Peaceful Arts facts for kids

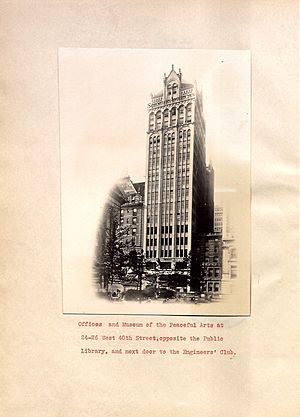

The Museum of the Peaceful Arts was a special museum located in Manhattan, New York City. It first opened its doors around 1920 at 24 West 40th Street. Later, it moved to the Daily News Building at 220 East 42nd Street. This museum eventually closed. Its ideas and purpose were later continued by the New York Museum of Science and Industry.

Contents

The Museum's Big Idea

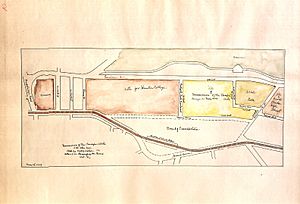

The idea for the Museum of the Peaceful Arts was very grand. It was first imagined as a huge group of twenty different museums. These museums were planned for Riverside Park in Manhattan. Later, there were plans to build them near the Jerome Park Reservoir in the Bronx.

The museum's original official document, called a charter, showed its wide goals. It aimed to create a lasting memory of a century of peace after the Treaty of Ghent was signed in 1814. The museum wanted to show how people used peaceful arts and industries to make progress.

It planned to have exhibits on many topics, including:

- Electricity

- Steam power

- Astronomy and how to navigate

- Safety tools

- Aviation (flying)

- Mechanical arts (how machines work)

- Agriculture (farming)

- Mining

- Labor (work)

- Efficiency (doing things well)

- Historic records

- Health and hygiene

- Textiles (fabrics)

- Ceramics and clays

- Architecture (building design)

- Scenic beauty

- Gardening

- Roads and building materials

- Commerce and trade

- Printing and books

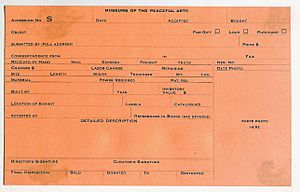

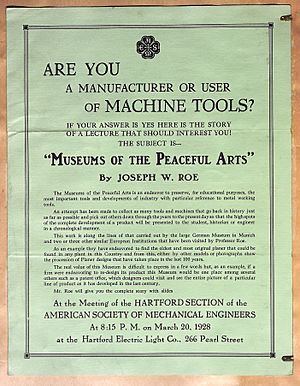

The museum also planned to have a library full of books and magazines about these subjects. There would be an auditorium for public meetings and lectures. The goal was to help schools, colleges, and universities. It wanted to be very useful for people in New York City, the state, and the whole country. The museum hoped to encourage education in business and industry.

Who Started the Museum?

George Frederick Kunz, a famous mineralogist and gem expert, was key to starting this museum. He suggested creating a new museum focused on "peaceful arts." While other museums showed science, war, or industry, this one would highlight peaceful inventions and progress.

A wealthy businessman named Henry R. Towne was very interested in Kunz's idea. He left $2.5 million in his will to New York for the Museum of Peaceful Arts. This generous gift helped experts travel to Europe. They studied museums like the German Museum in Munich. There, they saw amazing inventions like James Watt's first steam engine and Diesel's oil-compression engine. These studies helped New York and Chicago plan their own exhibits. The museum wanted to show working models of machines. This would help inventors and provide a place for new ideas.

Museum's Success and Exhibits

The Museum of the Peaceful Arts became quite popular. In 1929, The New Yorker magazine talked about it. They mentioned the museum had unusual machines. For example, visitors could see how much a steel rail could bend under a microscope. A movie also showed how air currents moved. The museum's collection began in 1913 with a group of business people. For two years, it was supported mainly by Henry F. Towne's large gift.

Fay Cluff Brown (1881-1968) was a physicist and inventor. He helped create and manage many educational exhibits for the museum. He was especially known for his work with the element selenium. Brown even invented a device using selenium that could turn printed text into sound!

One of the most interesting items the museum owned was America's very first submarine. This submarine, called the Holland, was bought from junk dealers by Dr. Peter J. Gibbons and his son. They then gave it to the Association for the Museum of the Peaceful Arts. Dr. George F. Kunz, who was also the president of Tiffany & Co., was the president of this new association.

Orville Wright's Interest

Many famous inventors were interested in the new museum. Orville Wright, one of the inventors of the airplane, wrote to George F. Kunz in May 1925. He talked about possibly giving one of his original Wright airplanes to the museum. He also shared his experiences with other museums.

Dear Mr. Kunz:

Orville Wright

The news that I might send our first airplane to the Kensington Museum brought me many letters. I am very busy with them, so please forgive this late reply.

I am sad about the situation at the Smithsonian Institution. It made it impossible for me to place our first airplane there. I wanted the plane to go to an American institution that had a historical and educational exhibit about flying. I didn't want it to be just a strange item in a museum. The Smithsonian is the only place in America that has such an exhibit now. But the Smithsonian did not want to show our 1903 plane, which was the first to fly. This was because it would make the 1903 Langley machine, which failed to fly, seem less important.

In 1910, when the Smithsonian asked for one of our machines, we suggested our original 1903 plane. They asked for our 1908 machine instead. ... The National Museum now has one of our 1909 planes.

I kept our 1903 machine, hoping things at the Smithsonian would change. But after almost 15 years, the situation got worse. So, I offered it to the Kensington Museum. At that time, I had not heard about your proposed Museum of the Peaceful Arts.

Sincerely,

Orville Wright's letter shows how important the Museum of the Peaceful Arts was becoming. It was seen as a place where significant historical inventions could be properly displayed and appreciated.

The Museum's Legacy

The historian of science, George Sarton, mentioned the Museum of the Peaceful Arts in his writings. He noted that George F. Kunz first came up with the idea in 1912. A lot of effort was made to raise enough money for the museum, but it was difficult. The museum was eventually replaced by the New York Museum of Science and Industry. This new museum continued the goal of educating people about science and industry.

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |