Nashville sit-ins facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Nashville sit-ins |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Sit-in movement in the Civil Rights Movement |

|||

Nashville's sit-in campaign targeted downtown lunch counters such as this one at Walgreens drugstore.

|

|||

| Date | February 13 – May 10, 1960 (2 months, 3 weeks and 6 days) |

||

| Location | |||

| Caused by |

|

||

| Resulted in |

|

||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Lead figures | |||

|

|||

The Nashville sit-ins were a series of peaceful protests in Nashville, Tennessee. They took place from February 13 to May 10, 1960. These protests aimed to end racial segregation at lunch counters in downtown Nashville.

This campaign was special because it succeeded early on. It also showed a strong focus on peaceful, nonviolent resistance. The Nashville sit-ins were part of a bigger movement across the southern United States. This movement started after similar protests in Greensboro, North Carolina.

During the Nashville sit-ins, students protested at many stores. Most participants were black college students. White onlookers often yelled at or physically attacked them. Even when attacked, the students did not fight back. More than 150 students were arrested for not leaving the lunch counters.

Lawyers, led by Z. Alexander Looby, defended the students in court. On April 19, Looby's home was bombed. Luckily, he was not hurt. Later that day, thousands of people marched to City Hall. They wanted to talk to Mayor Ben West about the violence. When asked if lunch counters should be desegregated, Mayor West agreed.

After talks between store owners and protest leaders, an agreement was made. On May 10, six downtown stores started serving black customers. This was a big step forward for civil rights.

Even after this success, protests against other segregated places continued. This lasted until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed. This law made segregation illegal everywhere in the U.S. Many leaders from the Nashville sit-ins became important figures in the Civil Rights Movement.

Contents

Understanding Segregation in the U.S.

In 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court made a decision called Plessy v. Ferguson. This decision said that separating people by race was okay, as long as facilities were "separate but equal." This led to many Jim Crow laws across the United States.

These laws made segregation legal in almost all public places. They allowed racial discrimination to happen, especially in the Southern states. In Nashville, like many Southern cities, African Americans faced many disadvantages. They went to schools that didn't get enough money. They were not allowed in many public places. They also had few chances for good jobs.

People in Nashville tried to fight Jim Crow laws as early as 1905. But it wasn't until 1958 that a group formed to truly challenge segregation. This group was the Nashville Christian Leadership Council.

Getting Ready for the Sit-ins

"We decided with great fear and anticipation we would desegregate downtown Nashville. No group of black people or other people anywhere in the United States in the 20th century, against the rapaciousness of a segregated system, ever thought about desegregating downtown."

The Nashville Christian Leadership Council (NCLC) was started by Reverend Kelly Miller Smith. This group was connected to Martin Luther King Jr.'s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Its goal was to gain civil rights for African Americans through peaceful civil disobedience. Reverend Smith believed that white Americans would be more open to desegregation if it happened through peaceful protests.

From 1958, the NCLC held workshops on nonviolent tactics. These workshops were led by James Lawson. He had learned about nonviolent resistance while working in India. Students from local colleges like Fisk University and Tennessee State University attended these sessions.

Many future Civil Rights leaders were part of Lawson's workshops. These included Marion Barry, James Bevel, Bernard Lafayette, John Lewis, Diane Nash, and C. T. Vivian.

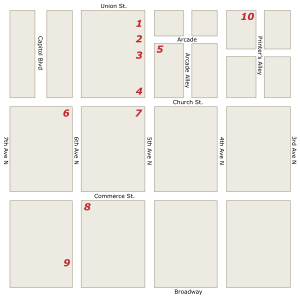

During these workshops, they decided to target downtown lunch counters first. At that time, black people could shop in downtown stores. But they could not eat in the stores' restaurants. The group felt lunch counters were a good target. They were easy to see and get to. They also showed how unfair segregation was every day.

In late 1959, James Lawson and other NCLC members met with store owners. They asked them to serve African Americans at their lunch counters. The owners said no, fearing they would lose business. So, students began practicing for sit-ins. They tried sitting at lunch counters at Harveys and Cain-Sloan stores. They wanted to see how people would react. They were refused service, but reactions varied. Harveys was polite, while Cain-Sloan was rude. These early tests were kept quiet.

The Main Protests Begin

Events in other cities made the Nashville students act faster. In early February 1960, a small sit-in in Greensboro, North Carolina, grew very quickly. It got a lot of media attention. When Lawson's group met, 500 new volunteers joined. Even though adult leaders wanted to wait, the students felt it was time to act.

The first big sit-in was on Saturday, February 13, 1960. About 124 students, mostly black, went into downtown stores. These included Woolworths, S. H. Kress, and McLellan stores. They asked to be served at the lunch counters. When staff refused, they sat for two hours and then left peacefully.

On the next Monday, many black churches in Nashville supported the students. They asked people to stop shopping at stores that practiced segregation. This boycott caused financial problems for the downtown stores.

The second sit-in happened on Thursday, February 18. More than 200 students went to Woolworths, S. H. Kress, McClellan, and Grants. The lunch counters closed right away. The students stayed for about 30 minutes and left without problems. The third sit-in was on February 20. About 350 students went to the same four stores plus Walgreens. White crowds gathered, but police watched and no violence occurred. The students stayed for almost three hours.

Tensions grew over the next week. On February 27, students held a fourth sit-in. This time, police were not there. White hecklers attacked several demonstrators. Some were pulled from their seats and beaten. When police arrived, the attackers ran away. Police then told the demonstrators to leave. When they refused, 81 students were arrested. They were charged with loitering and disorderly conduct.

The arrests brought a lot of media attention. National TV news and major newspapers covered the story. The students saw this media coverage as helpful. It showed their strong commitment to nonviolence.

More sit-ins happened over the next two months. This led to more arrests and attacks on students. Over 150 students were arrested in total. Throughout these protests, the students always remained peaceful. Their rules for conduct became a guide for other protests:

- "Do not strike back or curse if abused."

- "Do not laugh out."

- "Do not talk with the floor walker."

- "Do not leave your seat until your leader says so."

- "Do not block store entrances or aisles."

- "Do be polite and friendly at all times."

- "Do sit straight; always face the counter."

- "Do tell your leader about serious incidents."

- "Do politely send people asking for information to your leader."

- "Remember the teachings of Jesus, Gandhi, Martin Luther King. Love and nonviolence is the way."

Court Cases and a Teacher's Expulsion

The trials of the sit-in students drew a lot of attention. On February 29, the first day of trials, over 2,000 people gathered outside the courthouse. A team of 13 lawyers, led by Z. Alexander Looby, represented the students.

All arrested students were found guilty of disorderly conduct. They were fined $50 each. But the students refused to pay the fines. Instead, they chose to spend 33 days in the county workhouse. Diane Nash explained their choice. She said paying the fines would support the unfair arrests and convictions.

On the same day the trials began, a group of black ministers met with Mayor Ben West. James Lawson, a leader and teacher, was among them. A local newspaper criticized Lawson. This brought his activities to the attention of Vanderbilt University. Lawson was a student there. The university asked him to stop his involvement with the sit-ins. Lawson refused. He was then expelled from the university. The dean of the Divinity School resigned in protest.

A Committee for Change

On March 3, Mayor West formed a Biracial Committee. This committee was meant to ease racial tensions. It included leaders from two black universities. But it did not include any student protest leaders. The committee met for a month. On April 5, they suggested a partial solution. Each store would have one section for whites only. Another section would be for both whites and blacks.

The student leaders rejected this idea. They felt it was still based on segregation and was morally wrong. Less than a week later, the sit-ins started again. The boycott of downtown businesses also became stronger.

The Bombing of Looby's Home

At 5:30 AM on April 19, Z. Alexander Looby's home was attacked. Dynamite was thrown through a window. This was likely because he supported the protesters. The explosion badly damaged the house. But Looby and his wife, who were sleeping, were not hurt.

This event did not stop the protesters. Instead, it made the movement stronger. News of the bombing spread quickly. Around noon, nearly 4,000 people marched silently to City Hall. They wanted to confront the mayor. Mayor West met them on the steps.

Reverend C. T. Vivian read a statement. He accused the mayor of ignoring the unfairness of segregation. Diane Nash then asked the mayor if he thought it was wrong to discriminate based on race. Mayor West said yes, it was wrong. Nash then asked if he believed lunch counters should be desegregated. West said, "Yes." He added that it was up to the store managers.

Newspapers reported this event differently. The Tennessean focused on the mayor's agreement to desegregate. The Nashville Banner focused on his comment that it was up to the stores. This showed the different views of the newspapers. Still, the mayor's answer was a key moment for both activists and business owners.

The day after the bombing, Martin Luther King Jr. came to Nashville. He spoke at Fisk University. He praised the Nashville sit-in movement. He called it "the best organized and the most disciplined in the Southland."

Success: Desegregating Lunch Counters

After weeks of secret talks, an agreement was reached in early May. Small groups of African Americans would order food at downtown lunch counters. The store owners would know the day in advance. They would tell their employees to serve the customers without trouble. This would happen for a few weeks. Then, all controls would be removed.

On May 10, six downtown stores opened their lunch counters to black customers. The customers came in small groups and were served peacefully. At the same time, African Americans ended their six-week boycott of downtown stores. The plan worked well. The lunch counters were integrated without any more violence. Nashville became the first major city in the southern United States to begin desegregating its public places.

Even though the sit-ins ended, racism still existed in Nashville. For several years, more protests happened. These were at restaurants, movie theaters, and swimming pools. These actions continued until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed. This law made segregation illegal across the U.S. Many key figures from the sit-ins, like James Lawson and Kelly Miller Smith, later shared their experiences in a book.

Celebrating 50 Years of Change

In 2010, several events celebrated the 50th anniversary of the Nashville sit-ins.

- On January 20, Vanderbilt University held a discussion. It was called "Veterans of the Nashville Sit-ins – The Struggle Continues."

- The Tennessee State Museum had an exhibit. It was called "We Shall Not Be Moved: The 50th Anniversary of Tennessee's Civil Rights Sit-Ins."

- On February 10, Tennessee State University held a special event. Diane Nash was the main speaker.

- On February 12, Vanderbilt University hosted a discussion about media coverage. James Lawson and John Seigenthaler were speakers.

- The downtown Nashville library had a photo exhibit. It was called "Visions & Voices: The Civil Rights Movement in Nashville & Tennessee."

- Author Juan Williams led a discussion on civil rights. This happened at the downtown Nashville library on February 13.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |