Greensboro sit-ins facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Greensboro Sit-ins |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Sit-in movement in the Civil Rights Movement |

|||

The Greensboro Four: (left to right) David Richmond, Franklin McCain, Ezell A. Blair, Jr., and Joseph McNeil. Photo by Jack Moebes. Jack Moebes Photo Archive.

|

|||

| Date | February 1 – July 25, 1960 (5 months, 3 weeks and 3 days) |

||

| Location | |||

| Caused by |

|

||

| Resulted in |

|

||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Lead figures | |||

|

|||

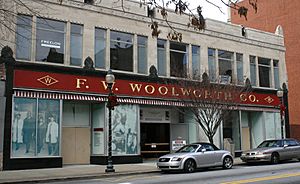

The Greensboro sit-ins were a series of peaceful protests that took place from February 1 to July 25, 1960. These protests happened mainly at the Woolworth store in Greensboro, North Carolina. This store is now the International Civil Rights Center and Museum. The sit-ins helped convince the F. W. Woolworth Company to end its rule of racial segregation in the Southern United States.

While there had been other sit-ins before, the Greensboro sit-ins became very famous. They helped start a bigger movement where about 70,000 people joined similar protests. These sit-ins also played a part in forming the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). This group was important in the Civil Rights Movement.

Contents

What Were Sit-ins?

A sit-in is a type of protest where people sit down in a public place and refuse to leave. They do this to show they are against something. It is a way of nonviolent protest. This means they protest peacefully without using any violence.

Before Greensboro, there were other sit-ins. In 1939, an African-American lawyer named Samuel Wilbert Tucker organized a sit-in at a library in Virginia. The Congress of Racial Equality also held sit-ins in cities like Chicago and St. Louis. In 1958, a sit-in in Kansas helped end segregation at a chain of drug stores.

The Activists' Plan: The Greensboro Four

The main people who started the Greensboro sit-ins were four young Black students. They were Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, Ezell Blair Jr., and David Richmond. They were all freshmen at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University. They often met in their dorm rooms to talk about how they could fight against segregation.

They were inspired by Martin Luther King Jr. and his ideas of peaceful protest. They especially wanted to change the rules at the F. W. Woolworth Company store in Greensboro. One time, McNeil was not allowed to buy a hot dog at a bus station because he was Black. After this, the four friends decided to take action.

Their plan was simple:

- They would sit at the "whites-only" lunch counter at Woolworth's.

- They would ask to be served food.

- When they were told no, they would not leave.

- They would do this every day until something changed.

Their goal was to get a lot of attention from the news. They hoped this would force Woolworth to end its segregation rules.

The Sit-ins Begin

On February 1, 1960, at 4:30 PM, the four students sat down at the lunch counter inside the Woolworth store. This counter had 66 seats. The students, now known as the A&T Four or the Greensboro Four, had already bought items from other parts of the store without problems. But when they asked for coffee and a donut at the lunch counter, they were refused service.

A white waitress told them, "We don't serve Negroes here." Blair pointed out that he had just been served a few feet away. The waitress replied, "Negroes eat at the other end." Some Black people in the store told them they were causing trouble. But an older white woman told them she was proud of them.

The store manager, Clarence Harris, asked them to leave. When they stayed, he called his boss. His boss thought the students would soon give up. So, Harris let them stay and did not call the police. The four students stayed until the store closed that night. Then, they went back to their university and asked more students to join them the next day.

More Students Join the Protest

On February 2, 1960, more than twenty Black students joined the sit-in. This group included four women. They sat at the counter from 11 AM to 3 PM, doing their schoolwork. They were again refused service and some white customers bothered them.

The sit-ins were reported in the local news on this second day. Reporters, a TV cameraman, and police officers were there. That night, the Student Executive Committee for Justice was formed. This group sent a letter to the president of F.W. Woolworth. They asked the company to stop discrimination.

On February 3, the number of protesters grew to over 60. Students from Dudley High School also joined. About one-third of the protesters were women, many from Bennett College. White customers continued to bother the students. Members of the Ku Klux Klan were also present. Woolworth's national office said they would "abide by local custom," meaning they would keep segregation.

On February 4, more than 300 people took part. This group included students from North Carolina A&T, Bennett College, and Dudley High School. They filled all the seats at the lunch counter. Three white female students from the Woman's College of the University of North Carolina also joined. The protests spread to another store, S. H. Kress & Co. Store managers and college leaders met to talk, but the stores still refused to end segregation.

Tensions Rise and Protests Spread

On February 5, the situation at Woolworth became tense. Fifty white men sat at the counter against the protesters. More than 300 people were at the store by 3 PM. Police removed two white customers for yelling. They also arrested three white customers before the store closed. Another meeting happened, but there was no solution.

On Saturday, February 6, over 1,400 North Carolina A&T students met. They voted to keep protesting. They went to the Woolworth store, filling it up. More than 1,000 protesters and people against the protest were in the store by noon. A bomb threat caused both the Woolworth and Kress stores to close.

On March 16, 1960, President Dwight D. Eisenhower spoke about the protests. He said he supported those fighting for equal rights.

The sit-in movement then spread to many other Southern cities. These included Winston-Salem, Durham, Raleigh, Charlotte, and Richmond. In Nashville, Tennessee, students had already started sit-ins. They were trained by civil rights activist James Lawson. The Nashville sit-ins helped end segregation at downtown lunch counters in May 1960. Most of these protests were peaceful, but some had violence.

The sit-ins spread to other public places too. These included bus stations, swimming pools, libraries, and museums. This happened mostly in the South.

Success of the Sit-ins

As the sit-ins continued, students started boycotting stores with segregated lunch counters. Sales at these stores dropped a lot. This caused the store owners to change their minds.

On Monday, July 25, 1960, Woolworth had lost nearly $200,000. Store manager Clarence Harris asked four Black employees to order food at the counter. These employees were Geneva Tisdale, Susie Morrison, Anetha Jones, and Charles Bess. They were quietly the first Black people to be served at a Woolworth lunch counter. Most stores soon ended segregation. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 later made segregation in public places illegal across the country.

The Lunch Counter Today

The original lunch counter from the Greensboro Woolworth store is now part of history. The International Civil Rights Center and Museum in Greensboro has most of the counter. Some seats were given to the National Museum of African American History and Culture in 2016. A four-seat part of the counter is also at the National Museum of American History.

Remembering the Sit-ins

The Greensboro sit-ins are remembered in many ways:

- In 1990, the street near the original store was renamed February One Place. This was to remember the date the first sit-in happened.

- In 2002, a sculpture called February One was put up at North Carolina A&T State University. It shows the Greensboro Four.

- On February 1, 2020, Google showed a special picture called a Google Doodle to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the sit-in.

- In 2022, a high school on the N.C. A&T campus was renamed "A&T Four Middle College."

In Film

- February One: The Story of the Greensboro Four is a 2003 documentary film shown on PBS.

- Seizing Justice: The Greensboro 4 is a 2010 documentary film for the Smithsonian Channel.

|

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |