Samuel Wilbert Tucker facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Samuel Wilbert Tucker

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | June 18, 1913 Alexandria, Virginia, United States

|

| Died | October 19, 1990 (aged 77) Richmond, Virginia, United States

|

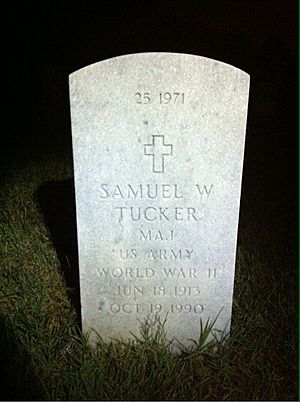

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Alma mater | Howard University |

| Occupation | Civil rights attorney |

| Spouse(s) | Julia E. Spaulding Tucker |

Samuel Wilbert Tucker (June 18, 1913 – October 19, 1990) was an American lawyer. He worked closely with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). His work for civil rights began when he organized a sit-in in 1939. This sit-in happened at the public library in Alexandria, Virginia, which was segregated at the time.

Tucker was a partner in a law firm in Richmond, Virginia. He argued and won several important civil rights cases. These cases went all the way to the Supreme Court of the United States. One of his most famous cases was Green v. County School Board of New Kent County. This case helped school integration more than almost any other Supreme Court decision since Brown v. Board of Education.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Samuel W. Tucker was born in Alexandria, Virginia, on June 18, 1913. His father, Samuel A. Tucker, was a real estate agent and a member of the NAACP. His mother was a teacher. Both made sure he received a good education. Samuel Tucker once said he got involved in the civil rights movement the day he was born, "I was born black."

Even though Alexandria was less segregated than some other cities, it did not have a high school for Black children. After finishing 8th grade, Samuel had to find a way to get a high school education. He traveled across the Potomac River to Washington, D.C., to attend Armstrong High School. Black children from Virginia would take the streetcar to get there.

In June 1927, when Samuel was 14, he and his two brothers and a friend refused to give up their seats on a streetcar. This happened after the streetcar crossed into Alexandria. A white woman thought one of the seats was only for white people. The police charged them with bad behavior. Samuel was fined $5, and his older brother George was fined $50. However, an all-white jury later found the young men not guilty.

Samuel started helping his father draft legal papers when he was young. He also read law books from Tom Watson, a lawyer who shared an office with his father. Samuel later attended Howard University. At Howard, Charles Hamilton Houston started the country's first program in civil rights law. Samuel earned his degree in 1933. He then qualified for the Virginia bar exam by studying in Watson's law office. He began practicing law in June 1934, when he turned 21.

After working with the Civilian Conservation Corps for two years, Samuel Tucker and his friend George Wilson began fighting segregation in Alexandria. They started with the public library, which opened in 1937. This library was only two blocks from Tucker's home, but it refused to give library cards to Black residents.

Fighting for Equal Rights

Tucker was allowed to practice law in 1934. This happened in the same courtroom where he had been found not guilty in the streetcar incident. He began his law practice in Alexandria.

Alexandria Library Sit-in

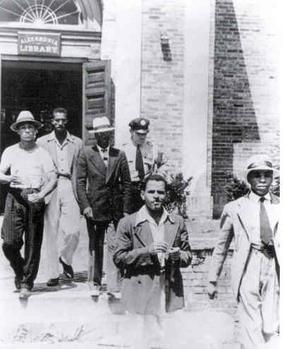

In 1939, Tucker organized a sit-in at the Alexandria Library. The library would not give library cards to Black people. On August 21, five young Black men, chosen and taught by Tucker, went into the library. They were William Evans, Otto L. Tucker, Edward Gaddis, Morris Murray, and Clarence Strange. Each man asked for a library card application. When they were refused, they each took a book and sat down to read. Police then removed them.

Tucker had told the men to dress nicely, speak politely, and not fight with the police. This was to make sure they wouldn't be found guilty of bad behavior. Tucker defended the men in court. The charges against them were dropped. As a result, a separate branch library was created for Black residents.

The local newspaper, the Alexandria Gazette, printed a short story about the sit-in. The Washington Post also mentioned it briefly. However, The Chicago Defender, a Black newspaper, put the story on its front page with a photo of the arrests. They called the protest a "test case" in Virginia. Other Black newspapers also covered the legal action. They reported how Tucker showed that if the men had been white, they would not have been arrested.

Even though Tucker successfully defended the sit-in participants, he was not happy with the "separate but equal" solution. He didn't want a new library just for Black people. He wanted Black people to be able to use the main library. In 1940, he wrote a letter saying he would not accept a card for the new Black-only library.

The photograph of the sit-in, showing the men calmly being led away by police, has become an important teaching tool. The city of Alexandria often remembers the sit-in. They use it to teach students about the Jim Crow era of segregation. Students from Samuel W. Tucker Elementary School even act out the sit-in and pose for recreated photos.

Service in the War and Moving On

World War II put a pause on Tucker's new law practice. He joined the army and served in the 366th Infantry. This group fought in Italy. Tucker became a major in the army.

After World War II, Tucker returned to Alexandria. But he felt there were too many Black lawyers there. So, he moved his law practice to Emporia, Virginia. This area was in the heart of Southside Virginia.

In Emporia, Tucker was the only Black lawyer. There were no Black judges or Black jurors. The white legal community in Greensville County often didn't like Tucker's way of defending his poor Black clients. He didn't just question the evidence; he also pointed out the racial unfairness in the legal system itself.

For example, Tucker defended a man named Jodie Bailey. Bailey was accused of hurting a white business owner who later died. With help from the NAACP, Tucker showed that for 30 years, no trial jury in Greensville County had included any Black jurors. The Virginia Supreme Court overturned Bailey's conviction, but he was convicted again in a new trial. Tucker also used statistics to help appeal the death sentences of the "Martinsville Seven." He argued that since 1908, Virginia had executed many Black men for certain crimes against white women, but no white men for similar crimes. However, judges did not accept this argument, and several clients were executed.

Fighting for the NAACP

As the Civil Rights Movement grew after the war, Tucker played a big part in its legal battles in Virginia. He filed lawsuits in almost 50 counties. By the time Brown v. Board of Education was decided in 1954 and 1955, the NAACP had many lawyers working together. They had filed many requests to end segregation in schools.

However, U.S. Senator Harry F. Byrd promised "Massive Resistance" to school desegregation. This meant he would strongly fight against it. Virginia then passed new laws to keep schools segregated. These laws also tried to stop the NAACP's work. They accused NAACP lawyers, including Tucker, of breaking these new laws.

Tucker was the only NAACP lawyer that the Virginia State Bar tried to stop from practicing law. This prosecution began in 1960. The NAACP sent a lawyer from Chicago to defend Tucker. The case was dismissed several times. The NAACP strongly supported Tucker, seeing this as an attempt to stop legal desegregation in Virginia. The case was finally dismissed in 1962. Later, in 1987, Tucker was honored for his work. He pointed out that he was now being recognized "for the very thing for which I'm being recognized today."

Work in Richmond and Other Counties

In the early 1960s, Tucker started a law firm in Richmond with Henry L. Marsh. They and the NAACP worked on the long legal fight to reopen public schools in Prince Edward County, Virginia. This county had closed its schools in 1959 to avoid desegregation. The schools only reopened in 1964 because of a court order. Tucker also continued to fight against racial discrimination in jury selection.

In 1966, the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund named Tucker "lawyer of the year." In 1967, Tucker had about 150 civil rights cases in various courts.

Tucker's biggest legal success was likely Green v. County School Board of New Kent County. This case challenged a "freedom-of-choice" plan. The school board claimed this plan would desegregate schools voluntarily. But it also allowed white children to attend private "segregation academies" at public expense. The case went to the Supreme Court of the United States. Tucker argued that the plan was just another way to keep schools segregated.

In May 1968, the Supreme Court ruled that the "freedom-of-choice" plan was not good enough. The Court said that school boards had a "duty" to desegregate their schools. They said that the old idea of "mere deliberate speed" for desegregation was no longer acceptable. The next day, Tucker appeared in court with 40 files of desegregation cases he wanted reopened.

Besides taking cases to court, Tucker was also active in the NAACP's leadership. He led the legal staff for the Virginia State Conference. He also represented Virginia, Maryland, and Washington D.C. on the national board of directors.

Political Work and Awards

Tucker ran for U.S. Congress twice. He ran against Watkins Abbitt, who supported segregation. Tucker knew he probably wouldn't win, but he believed it was important to show the protests and hopes of Black voters in the district.

In 1976, the NAACP honored Tucker with the William Robert Ming Advocacy Award. This award recognized his personal sacrifices and dedication to his legal work.

Later Life and Legacy

Samuel Tucker passed away on October 19, 1990. He was survived by his wife, Julia. They did not have children. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery, sharing a tombstone with his older brother George. The Robert H. Robinson Library, which opened in 1940 and closed in 1959, later became the Alexandria Black History Museum.

In 1998, Emporia, Virginia, put up a monument in Tucker's honor. The monument calls him "an effective, unrelenting advocate for freedom, equality and human dignity."

In 2000, Alexandria, Virginia, named a new school after him: Samuel W. Tucker Elementary School. This honored his life's work in desegregation and education. In 2014, the city's library started collecting money for the Samuel W. Tucker Fund. This fund helps expand a collection of civil rights history.

Also in 2000, the Richmond City Council voted to rename a bridge after Tucker. This bridge was formerly named after a Confederate General.

Since 2001, the Oliver W. Hill & Samuel W. Tucker Scholarship Committee has given scholarships to law students. These scholarships help future lawyers, especially minority students, learn about the legal profession.

|

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |