Nedîm facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Nedîm

Effendi

|

|

|---|---|

| نديم | |

A later artist's impression of Nedîm, no extant contemporary depictions of him exist.

|

|

| Born |

Ahmed

c. 1681 Constantinople (present-day Istanbul), Ottoman Empire

|

| Died | 1730 (aged 48–49) Beşiktaş, Constantinople, Ottoman Empire

|

| Resting place | Karacaahmet Cemetery, Scutari, Constantinople, Ottoman Empire |

| Occupation |

|

| Spouse(s) | Ümmügülsüm Hanım |

| Writing career | |

| Language | |

| Period | Tulip Era |

| Genres |

|

| Literary movement | Diwan vernacularism (Turkish: Mahallîleşme) |

Ahmed Effendi, known by his pen name Nedîm (meaning "companion" or "friend"), was a famous Ottoman poet. He lived during a time called the Tulip period (around 1703-1730). This was a time of peace and new ideas in the Ottoman Empire.

Nedîm became very famous during the rule of Sultan Ahmed III. He was known for his fresh and lively poems. He also helped bring popular folk songs, called türkü and şarkı, into the formal court poetry.

Contents

Life of Nedîm

Nedîm's Early Life and Education

We don't know a lot about Nedîm's early years. He was born in Constantinople (today's Istanbul) around 1681. His birth name was Ahmed.

Nedîm's father was a Kadı, which was like a judge or legal scholar. His family was involved in the Ottoman government. Because of this, Nedîm likely had a very good education. He studied many subjects, including science. He also learned enough Arabic and Persian to write poetry.

After his studies, he passed an important exam. This exam was led by Shaykh-al Islam Ebezâde Abdullah Effendi, a top religious leader. Nedîm then started working as a scholar in a madrasa, which is a type of school. He continued to teach and study in different madrasas. Eventually, he became a leading scholar at the Sahn-ı Seman Madrasas. He taught various subjects until he passed away in 1730.

Nedîm's Active Years as a Poet

Nedîm probably started writing poems even before 1703. His more traditional poems, called qasidas (long poems praising someone), became well-known. These poems helped him connect with important officials. One of these was Nevşehirli Damat Ibrahim Pasha, a powerful leader. Ibrahim Pasha liked Nedîm's poems a lot and supported his work.

Nedîm was also known for challenging the poetry styles of his time. Many poets in Constantinople followed the Nâbî school. This style focused on very philosophical and teaching-like poems called ghazals (short love poems). Nedîm's poems were more about feelings and everyday life. He became a leader of his own style, which people called Nedîmâne.

Nedîm knew his poetry was new and different. He even wrote about it in his poems:

Ma‘lûmdur benim sühanım mahlas istemez

Fark eyler onu şehrimizin nüktedânları

My words are clear, they don't need my name,

The clever writers of our city will know them as mine.

During these years, Nedîm was a respected teacher. He was invited to special sessions during Ramadan to share his knowledge of Islamic topics. He also worked in many different government roles. He was a scholar, a chief librarian, and a translator of history books. He also worked as an assistant to a kadı (judge). Later, he even became the Sultan's own nedîm (companion). All this time, he kept writing poetry.

Many people noticed Nedîm's unique style. He used everyday language and brought new ideas to poetry. A famous writer named Sâlim called him the "fresh-tongued" poet of his time. Other poets even wrote poems that copied Nedîm's style. Even with this early fame, he wasn't as celebrated then as he is today. His collected poems were not put together into a Diwan (a collection of poems) until 1736.

Nedîm's Final Years

There are different stories about how Nedîm's life ended. We know he struggled with a mental illness called illet-i vehîme, which means a serious anxiety disorder. He was also described as having a "fragile nature." He was married to Ümmügülsüm Hanım, and they had one child.

Most sources say he died during the Patrona Halil Rebellion in 1730. This was a big uprising that ended the Tulip Period. Some people say he accidentally fell from his house roof during the rebellion. Others believe he died from a disease that caused tremors, similar to Parkinson's. No matter the exact cause, he continued to work as a scholar at the Sekban Ali Pasha Madrasa until his last days.

Nedîm's Works

Today, Nedîm is considered one of the three greatest poets in Ottoman Divan poetry. The other two are Fuzûlî and Bâkî. However, he wasn't always seen this way. In his own time, Sultan Ahmed III gave the title "leader of poets" to other poets, not Nedîm. This might be because Nedîm's poetry was very new and different for its time.

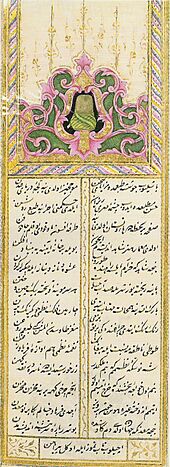

Nedîm's collected works are very varied. They include 170 ghazals, 34 şarkıs (songs), and 44 qasidas. He also wrote many other types of poems. Some of his poems were traditional, while others were very modern and even satirical (making fun of things).

Because his works are so diverse, people have studied them in many different ways. Some scholars, like H. A. R. Gibb, said Nedîm's style was local and focused on real-life descriptions. They also noted that his poems didn't focus much on Sufism (a mystical branch of Islam). However, more recent studies have shown that these older ideas might have been influenced by the times they were written in.

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |