OR-7 facts for kids

OR-7 in Jackson County, Oregon, in May 2014

|

|

| Other name(s) | Journey |

|---|---|

| Species | Gray wolf (Canis lupus) |

| Breed | Northwestern wolf subspecies (C. l. occidentalis) |

| Sex | Male |

| Born | April 2009 Oregon |

| Died | 2020 (presumed) |

| Nation from | United States |

| Parent(s) | B-300F/OR-2F (mother) & OR-4M |

| Offspring | 7 pups |

| Weight | 90 lb (41 kg) in February 2011 |

| Appearance | Gray |

| Named after | 7th wolf collared in Oregon |

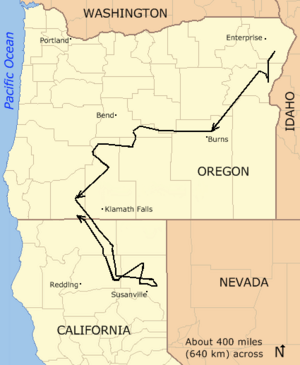

OR-7, also known as Journey, was a male gray wolf. He became famous for traveling a very long distance across the U.S. states of Oregon and northern California. Scientists tracked him using a special collar.

OR-7 left his family pack in Oregon in 2011. He traveled over 1,000 miles (1,600 km) looking for a mate and new territory. He was the first wild wolf seen in western Oregon since 1947. He was also the first in California since 1924.

By 2014, OR-7 found a mate in the Rogue River area of southern Oregon. In 2015, officials named their family the Rogue Pack. This was the first wolf pack in western Oregon. OR-7's tracking collar stopped working in October 2015. After that, scientists used trail cameras and sightings to watch the pack.

OR-7 was not seen during the wolf count in 2020. It is believed he died around that time. He was about 11 years old, which is quite old for a wild wolf.

Contents

Why Wolves Were Protected

Wolves in the United States were once in danger of disappearing. Because of this, they were protected by a law called the Endangered Species Act in 1978. This law helps animals that are at risk.

Later, wolves were brought back to Idaho. From there, they started to spread into other areas, including Oregon. When wolves began crossing into Oregon from Idaho in the 1990s, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) started to study them.

How Wolves Are Tracked

Wildlife experts would catch wolves and fit them with GPS tracking collars. These collars send daily reports about where the wolves are. Each collared wolf was given a special number. OR-7 was the seventh wolf to get a collar in Oregon.

Most wolves stayed in the northeastern part of Oregon, where there was plenty of food like elk and deer. But in 2010, scientists noticed some wolves in the Cascade Mountains. They wanted to know if these were just passing through or if they were settling down.

In February 2011, OR-7 was part of the Imnaha Pack in northeastern Oregon. This was Oregon's first wolf pack since wolves returned to the state. OR-7 was a young male from the pack's second group of pups.

OR-7's Amazing Journey

Young male wolves often leave their birth pack to find a mate and new territory. OR-7 left the Imnaha Pack in September 2011. In November, he was seen in western Oregon. This was the first time a wild wolf had been confirmed in southwestern Oregon since 1946.

Crossing State Lines

In late December 2011, OR-7 crossed into northern California. He was the first wolf seen in California since 1924. He explored different counties in California before heading back to Oregon in March 2012. By then, he had traveled over 1,000 miles (1,600 km).

OR-7 went back to California for the summer of 2012. He returned to Oregon in March 2013. His long journey caught the attention of people all over the world.

Becoming "Journey"

In 2012, a group called Oregon Wild held a contest for children to name the wolf. The winning name was "Journey." This contest helped make OR-7 very famous. The group hoped that his fame would help protect him.

Forming the Rogue Pack

In May 2014, cameras in the Rogue River – Siskiyou National Forest took pictures of OR-7 with a female wolf. A month later, biologists found two wolf pups. DNA tests confirmed that OR-7 was the father and the female was the mother. She was related to other wolf packs in northeastern Oregon.

New Pups and Protection

The birth of these pups near the California border was exciting. It meant that wolves might start living in California again. In June 2014, California decided to protect wolves under its own Endangered Species Act.

The adult wolves and their pups stayed in the Rogue River area. In early 2015, their group was officially named the Rogue Pack. This was Oregon's ninth wolf pack. By July 2015, OR-7 and his mate had a second group of pups. Trail cameras later showed two new pups, bringing the pack size to seven. By 2016, the pack had grown to nine wolves.

Tracking the Pack

OR-7's GPS tracking unit stopped working in October 2015. Officials wanted to replace it to keep tracking the pack. However, they couldn't catch OR-7 or other pack members. So, they relied on trail cameras and sightings.

In October 2017, biologists were able to collar OR-54. She was thought to be OR-7's daughter and was traveling with the Rogue Pack. Her collar helped officials track the pack's movements. Sadly, OR-54 was found dead in February 2020.

OR-7 was last seen in Oregon in the fall of 2019. Since he wasn't found in the winter wolf count of 2020, it's believed he passed away.

Since 2015, other wolves have also moved into western Oregon. This shows that the wolf population in Oregon is growing. In 2017, there were at least 112 wolves in the state.

Wolves Spreading to California

In 2015, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) shared a photo of the Shasta Pack in California. This pack had two adult wolves and five pups. The adult wolves were OR-7's brothers and sisters.

In 2017, scientists found another pack in California called the Lassen Pack. At least three pups from this pack were related to OR-7. One of OR-7's male offspring had pups, making Journey a grandfather! The Lassen Pack is California's second wolf pack since wolves were removed from the state in the 1920s.

More recently, in November 2020, a male wolf named OR-85 traveled from Oregon to California. By January 2021, another wolf, likely a female, joined him. In August 2021, it was confirmed that the Whaleback Pack (OR-85 and his mate) had 7 pups. The Lassen Pack also had 6 pups. This shows that wolves continue to expand their territory in California.

See also

- List of grey wolf populations by country

- List of wolves

- Slavc

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |