Old Post Office (Washington, D.C.) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

Old Post Office and Clock Tower

|

|

|

U.S. Historic district

Contributing property |

|

The Old Post Office Building in 2012

|

|

| Location | Washington, D.C. |

|---|---|

| Built | 1892 to 1899 |

| Architect | Willoughby J. Edbrooke (original building) Karn Charuhas Chapman & Twohey (East Atrium) |

| Architectural style | Romanesque Revival (original building) Modernist (East Atrium) |

| Part of | Pennsylvania Avenue National Historic Site (ID66000865) |

| NRHP reference No. | 73002105 |

| Added to NRHP | April 11, 1973 |

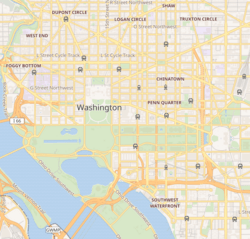

The Old Post Office building, also known as the Old Post Office and Clock Tower, is a famous landmark in Washington, D.C.. You can find it at 1100 Pennsylvania Avenue NW. It's part of the Pennsylvania Avenue National Historic Site.

Construction of this building started in 1892 and finished in 1899. It's a great example of Romanesque Revival architecture, a popular style from the 1800s. Its tall clock tower is the third highest structure in Washington, D.C., not counting radio towers.

The building was the city's main General Post Office until 1914. After that, it became a federal office building. It was almost torn down several times, especially in the 1920s and 1970s. But people fought to save it!

Major updates happened in 1976 and 1983. The 1983 changes added a food court, shops, and a cool skylight over the central area. This part of the building became known as the "Old Post Office Pavilion." In 2013, the building was leased and later became a luxury hotel. It opened as the Trump International Hotel Washington, D.C. in 2016. In 2022, it was sold and reopened as the Waldorf Astoria Washington DC.

The building's 315-foot (96-meter) clock tower holds special bells called the "Bells of Congress." From its observation deck, you can see amazing views of the city.

Contents

Building the Old Post Office

The United States Congress decided to build a new post office for Washington, D.C., in 1890. The spot chosen was at Pennsylvania Avenue and 12th Street. Architect Willoughby J. Edbrooke designed the building. He used the Romanesque Revival architecture style. Building started in 1892 and was finished in 1899. The total cost was $3 million.

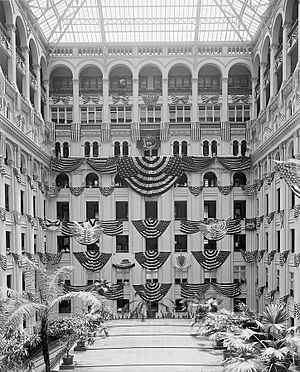

When it was finished, the Post Office Building had the biggest open space inside the city. Its clock tower reached 315 feet (96 meters) high. It was also the first building in D.C. to have a steel frame. It was also the first to have electrical wiring built into its design. The building featured fancy elevators and a glass-covered central area called an atrium. Marble was used for floors, railings, and walls.

The atrium was 196 feet (60 meters) high. Ten floors of balconies looked down into this space. It had over 39,000 electric lights and its own power generator. Even with all these features, the building had some problems. Reports said the windows leaked, and some construction was not perfect. It also quickly became too small for all the government offices.

Early Years of the Building

In the early 1900s, there were ideas to tear down many buildings in the area. However, the important McMillan Plan of 1902 suggested keeping the Old Post Office. Even so, some people still wanted it removed. They thought its style didn't fit with other government buildings.

The clock in the tower was first mechanical. It used a heavy weight and cable to keep time. In 1956, the weight fell through two floors! After that, an electric clock replaced the old mechanical one.

In 1914, the main post office moved to a bigger building near Union Station. This new location was better for mail delivery by train. The building at 12th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue then became known as the "old" post office. For the next 40 years, it was used for different government offices.

The Old Post Office Building was almost demolished again in the 1920s and 1930s. This was during the construction of the Federal Triangle complex. Many new government buildings were planned in a different style. But tearing down a strong, relatively new building during the Great Depression seemed wasteful. So, the Old Post Office was saved.

The tower of the Old Post Office slowly became a symbol of the city. It was even used in films shown in other countries.

Saving the Building in the 1970s

By the 1950s, the area around the Old Post Office was not looking its best. After seeing this, President John F. Kennedy started a plan to improve Pennsylvania Avenue. His plan suggested keeping the Old Post Office.

Later, a new commission suggested tearing down the Old Post Office. This was to complete the Federal Triangle plan. But a group of citizens and architects formed "Don't Tear It Down." They worked hard to save the building. This group included Nancy Hanks, a very influential person in the arts.

Their efforts gained support in the United States Senate. In 1971, a federal group also recommended keeping the building. The Nixon administration still wanted to tear it down. They wanted to finish the Federal Triangle for the United States Bicentennial in 1976. But Senator Mike Gravel strongly opposed this. In 1972, Congress voted against giving money to demolish the Old Post Office.

Renovation and Reopening

The Old Post Office was officially added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973. This meant it was recognized as an important historic site. The government then decided to save and renovate the building.

A big renovation started in 1977. The building really needed it. The roof leaked, and there was mold. The heating system often broke down.

1979–1983 Renovation

In 1978, the government looked for a partner to redevelop the building. A group of four firms won the project. They agreed to a 55-year lease.

The $29 million renovation was finished in 1983. Much of the inside was changed to use the space better. But some historic parts were kept. New marble was added, and the inside was repainted in soft colors. A glass elevator was added to reach the observation deck. A new grand staircase was also built.

The renovated building officially opened on April 19, 1983. Vice President George H. W. Bush was there. The Bells of Congress rang from the clock tower to celebrate. The first three floors became shops and restaurants. This area was called the "Old Post Office Pavilion." In 1986, Congress officially renamed the Old Post Office the Nancy Hanks Center, honoring the person who helped save it.

New Year's Eve Fun

From 1984, a special New Year's Eve event took place at the Old Post Office. The city government and the United States Postal Service created a huge wooden replica of the "Love" stamp. Each New Year's Eve, a new version of the stamp was lowered from the Clock Tower around midnight.

People celebrated with music and dancing inside the building. Outside, fireworks and searchlights lit up the sky. Celebrities performed on outdoor stages. At midnight, bells rang, and neon signs flashed "Happy New Year." The stamp grew larger over the years. By 1990, it was 20 feet by 30 feet and weighed two tons!

Up to 100,000 people came to this event each year. In 1990, the Postal Service stopped dropping the stamp. The outdoor celebrations ended, but smaller parties continued inside.

Changes and New Uses

Even with the renovations, the Old Post Office Pavilion faced challenges. The retail space was not well designed. It also didn't have storefronts on the outside to attract shoppers. Revenues changed a lot with the seasons.

In the early 1990s, an expansion called the East Atrium was built. This glass-enclosed addition opened in 1992. It added 100,000 square feet of space. The East Atrium aimed to bring in larger and more upscale shops. However, it struggled to find tenants.

By 1993, the Old Post Office Pavilion was having financial problems. It was behind on its rent. Experts said the cost of heating and cooling the huge atrium was a problem. Also, many shops kept leaving. The East Atrium was often empty.

In 1997, a hotel company wanted to turn the upper floors into hotel rooms. They also wanted to open up the Pennsylvania Avenue side for more shops. But the government didn't agree to their terms.

By 2000, the retail operations were not doing well. The East Atrium was closed. The government realized that a retail/office mix wasn't working. They started thinking about turning the whole building into a hotel. This idea became more popular after a nearby historic building was successfully turned into the Hotel Monaco.

Becoming a Hotel

In 2013, the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) leased the property for 60 years. The lease went to a group led by "DJT Holdings LLC." This company was owned by Donald Trump. Trump developed the property into a luxury hotel. It was named the Trump International Hotel Washington, D.C. It opened in September 2016.

During Donald Trump's time as president, the hotel often became a place for political protests. In 2019, the Trump Organization said it might sell the hotel.

The hotel closed on May 11, 2022. It was sold to CGI Merchant Group. It then reopened as the Waldorf Astoria Washington DC on June 1, 2022.

Clock Tower and Bells

The Old Post Office Building's 315-foot (96-meter) clock tower is the third-highest building in Washington, D.C. Only the Washington Monument and the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception are taller. The tower's observation deck is 270 feet (82 meters) high. It offers amazing views of the city. Inside the tower, you can see how the clock works.

The Clock Tower is home to the "Bells of Congress." These 10 bells are copies of bells found in Westminster Abbey in London. Sir David Wills donated them to the United States in 1976. This was to celebrate America's Bicentennial. The bells were installed in the tower in 1983.

The bells range in weight from 300 to 3,000 pounds (136 to 1,360 kg). They are made of copper and tin. Each bell has the Great Seal of the United States and other symbols. The tower was not originally built for bells. So, engineers had to make changes to support their weight.

The Washington Ringing Society rings the Bells of Congress every Thursday evening. They also ring them on special occasions. These bells are one of the largest sets of change ringing bells in North America. Visitors can see the ropes used to ring the bells.

National Park Service rangers give tours of the Clock Tower. These tours let people explore the tower and learn about its history.