Olufunmilayo Olopade facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Olufunmilayo Olopade

|

|

|---|---|

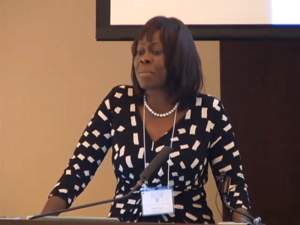

Olopade in 2012

|

|

| Born | 1957 (age 68–69) Nigeria

|

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | University of Ibadan |

| Spouse(s) | Christopher Sola Olopade |

| Children | Dayo Olopade |

| Medical career | |

| Field | Hematology |

| Institutions | University of Chicago |

| Sub-specialties | Oncology |

| Research | BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes |

| Awards | MacArthur Fellows Program, Villanova University Mendel Medal, Four Freedoms Award |

Olufunmilayo I. Olopade was born in 1957. She is a Nigerian-American doctor who specializes in treating blood cancers and other cancers. She is a special professor at the University of Chicago and helps improve health around the world. Dr. Olopade also leads a clinic at the University of Chicago Hospital that helps people understand their risk for cancer.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Olufunmilayo Olopade grew up in Nigeria. She was the fifth of six children. From a young age, she wanted to become a doctor. This was because there were not many doctors or medical supplies in Nigerian villages, and people really needed them.

She went to St Anne's School in Ibadan for her high school education. Later, she studied at the University of Ibadan in Nigeria. She earned her medical degree (MBBS) in 1980.

Career and Research

Dr. Olopade started her medical career in 1980. She worked as a medical officer at the Nigerian Navy Hospital. In 1983, she moved to the United States. She worked at Cook County Hospital in Chicago until 1987.

In 1991, Dr. Olopade joined the University of Chicago. There, she became a professor in blood cancer and cancer treatment. She also became the Dean of Global Health. She leads the Center for Clinical Cancer Genetics at the University of Chicago.

Dr. Olopade works closely with the Breast Cancer Research Foundation. She has done a lot of important research on how certain genes, called BRCA1 and BRCA2, affect breast cancer. Her work especially focuses on women of African heritage.

She is a member of several important medical groups. These include the American Association for Cancer Research and the American College of Physicians.

Discoveries in Cancer Genetics

In 1987, while at the University of Chicago, Dr. Olopade found a gene that helps stop tumors from growing. This was a big step in understanding cancer.

In 1992, she helped create the University of Chicago's Center for Clinical Cancer Genetics. Here, she discovered that African-American women often get breast cancer at a younger age than white women.

In 2003, she started a new study. She looked at breast cancer and genetics in African women from Nigeria to Senegal. She also studied African-American women in Chicago. By 2005, she found something very important. About 80% of tumors in African women did not need estrogen to grow. This was different from Caucasian women, where only about 20% of tumors were like this. She also found that this difference was due to how genes were working in these different groups of women.

Awards and Honors

Dr. Olopade has received many awards for her important work:

- 1975: Nigerian Federal Government Merit Award

- 1978: Nigerian Medical Association Award for Excellence in Pediatrics

- 1980: Nigerian Medical Association Award for Excellence in Medicine

- 1990: Ellen Ruth Lebow Fellowship

- 1991: American Society for Clinical Oncology Young Investigator Award

- 1992: James S. McDonnell Foundation Scholar Award

- 2000: Doris Duke Distinguished Clinical Scientist Award

- 2003: Phenomenal Woman Award for work within the African-American Community

- 2005: Access Community Network's Heroes in Healthcare Award

- 2005: MacArthur Fellows Program

- 2015: Four Freedoms Award

- 2017: Villanova University Mendel Medal

- 2019: The Lincoln Academy of Illinois gave Dr. Olopade the Order of Lincoln award. This is the highest honor given by the State of Illinois.

- 2021: She became a member of the U. S. National Academy of Sciences.

The "Genius Grant"

In 2005, Olufunmilayo Olopade was one of three African-Americans to receive a special award from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. This award was for $500,000 and was sometimes called the "genius grant." It was given to support her groundbreaking discoveries in diseases and health. This grant allowed her to continue her important research without many restrictions.

Family Life

In 1983, Olufunmilayo married Christopher Sola Olopade. He is also a physician at the University of Chicago. They have two daughters, including journalist Dayo Olopade, and one son.

See also

In Spanish: Olufunmilayo Olopade para niños

In Spanish: Olufunmilayo Olopade para niños

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |