Order of Railroad Telegraphers facts for kids

The Order of Railroad Telegraphers (ORT) was a special group, like a club or a team, for people who worked as telegraph operators on railroads in the United States. It started in the late 1800s. Its main goal was to help these workers get fair pay, good working conditions, and to make sure their jobs were safe.

Contents

How It Started

Telegraphs and Trains

In the early days of railroads, telegraph lines often ran right next to the tracks. In 1851, the telegraph was first used to help control train movements by Charles Minot. He was a superintendent for the Erie Railroad.

By the 1860s and 1870s, this became a common practice. Telegraphers worked in small stations along the railroad line. They would get orders from a central dispatcher. They also reported where trains were. These orders were written down and given to train crews as they passed by.

This system made single-track railroads much more efficient. Two trains could use the same track, even if they were going in opposite directions. The dispatcher would tell one train to wait on a side track. The local telegraph operator would keep track of train times. They also set the track switches for trains to move onto side tracks.

Why Telegraphers Were Important

Before time zones were created, local time could be different at each station. A mistake in timing when two trains met could cause a big accident. So, railroad telegraphers were very important. They helped trains run safely and on time. Think of them like air traffic controllers for trains!

In the 1860s, telegraphers started forming groups to improve their jobs. They wanted better pay and working conditions. After a strike in 1883 didn't work out, railroad telegraphers decided they were different from other telegraph operators. They focused on their own unique needs.

On June 9, 1886, a group of railroad telegraphers met in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. This meeting was organized by Ambrose D. Thurston. He published a magazine called Railroad Telegrapher. They formed the Order of Railway Telegraphers of North America. Only telegraphers who worked or had worked for railroads could join.

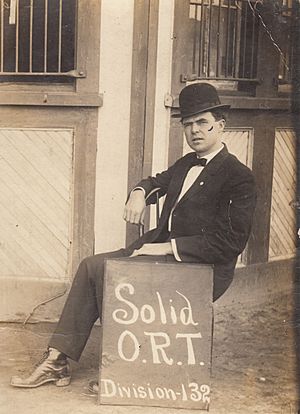

At first, the ORT was more like a social club than a strong union. It was similar to other railroad unions that were less likely to strike. Their rules even said members should only strike in extreme cases. By March 1887, they had 2,250 members. By March 1889, this number grew to 9,000.

Growing Stronger

Becoming More Active

In the early 1890s, members wanted the ORT to do more. They wanted the union to fight harder for better pay and working conditions. In 1891, the ORT changed its rules. It officially became a "protective" group. This meant it could call strikes if talks with the railroads failed. At this time, they also changed their name to "Order of Railroad Telegraphers."

Sometimes, operators would go on "wildcat" strikes without asking the ORT leaders first. The leaders then had to support these strikes that had already started. From 1890 to 1892, times were good for railroads. They were willing to work with the ORT. They signed agreements about wages and working hours. Agreements were made with several big railroads, like the Union Pacific and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

In 1892, D.G. Ramsay took over as the leader of the ORT. He promised to be tougher with the railroads.

Tough Times in the 1890s

The Panic of 1893 was a big economic crisis. It hit the railroad industry hard. Many large railroads went bankrupt. This led to more arguments between the ORT and the railroads. A strike began against the Lehigh Valley Railroad in November 1893. This happened because the railroad refused to talk with the ORT and other big railroad unions.

Government groups in New York and New Jersey helped solve the problem. They used mediation, which means they helped both sides talk and find a solution. The strike ended in December 1893. This was a big win for the ORT. The railroad agreed to hire back all the striking workers.

The Panic of 1893 also caused ORT membership to drop. It went from 18,000 members in 1893 to only 5,000 in 1895. Many members left the ORT to join a new union, the American Railway Union. This happened when the ORT leaders did not support a strike by other workers in 1894.

Steady Growth

In the late 1890s, the ORT got better at organizing its members. They added a special department in 1898 to help members who were sick or jobless. They also started allowing switch levermen to join.

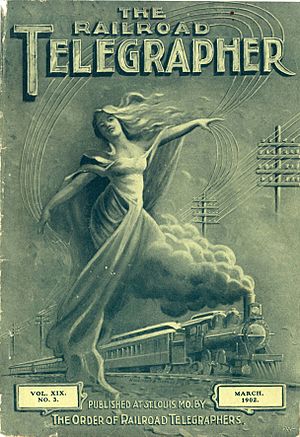

The ORT became an international union in 1896. They supported a strike against the Canadian Pacific Railway. This strike was about the railroad firing union workers and refusing to talk about wages. The strike ended after nine days. The railroad agreed to let the ORT represent its telegraphers. This win helped the ORT grow in Canada. They also started organizing in Mexico. Because of this, their magazine, Railroad Telegrapher, began to include sections in French and Spanish.

The ORT moved its main office several times. First, from Vinton, Iowa, to Peoria, Illinois, in 1895. Then, in 1899, they moved to St. Louis, Missouri. They also joined the American Federation of Labor. By 1901, the ORT had 30 local groups and 10,000 members. This was double the number from 1895.

Women in the ORT

The ORT welcomed women telegraphers from the very beginning. The Railroad Telegrapher magazine even had a section just for women operators. Women played an active role in getting new members and helping with local union activities.

Hattie Todd Pickard joined the ORT in 1890. She later became an Assistant Chief for one of the ORT's groups. Katherine B. Davidson was elected as a District Representative in 1905. Ola Delight Smith joined in 1906 and became a well-known labor organizer and writer.

Working Hours and Laws

The Hours of Service Act

Working long hours was a big problem for railroad telegraphers. Since they were like "air traffic controllers" for trains, being tired could cause serious accidents. In 1907, a bill was introduced in Congress to limit how many hours railroad workers could be on duty. This was called the La Follette Hours of Service Act.

A separate bill was also proposed to limit telegraphers to nine hours of work in a 24-hour period. Some people tried to change this to twelve hours. This made ORT members very angry. They immediately sent many telegrams to their representatives in Congress. This protest worked! The original nine-hour limit was put back. President Theodore Roosevelt signed the La Follette Hours of Service Act into law on March 4, 1907.

Even with this law, operators at small stations might still work long hours. Sometimes their work time was spread out over a longer period, called a "split trick." The ORT wanted to reduce the workday even more, to eight hours, and get rid of split tricks. However, the ORT didn't work closely with other railroad unions on this. So, when the Adamson Act was passed in 1917, it set an eight-hour day for most railroad workers, but it didn't clearly include telegraphers.

Government Control and Growth

World War I and Railroads

When the U.S. entered World War I, the government took control of the railroads and telegraph systems. On December 26, 1917, the United States Railroad Administration (USRA) took over the railroads. The USRA generally supported unions. During this time, railroad operators got an eight-hour workday. The ORT also gained the power to negotiate for all its members across the country.

The ORT signed agreements with several major railroads. By 1917, ORT membership had grown to 46,000. A special board was set up to handle railroad wages. The ORT's leader asked for a 40 percent pay raise and an eight-hour day. While some raises were given, they were much less than requested. This made ORT members unhappy. In 1919, a new leader, E. J. Manion, was elected.

Government control of the railroads ended on March 1, 1920. The ORT then had to negotiate new agreements with each railroad separately.

The 1920s and Beyond

The early 1920s were the best years for ORT membership. By 1922, the union had 78,000 members in the U.S., Canada, and Mexico. Some railroads kept the same agreements they had made during government control. A strike against the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad in 1925 ended with the railroad agreeing to the union's demands.

The Great Depression and Changes

Membership in the ORT started to fall after the stock market crash of 1929. This was due to the bad economy. Also, new technology called "centralized traffic control" meant fewer telegraphers were needed at each station. Membership dropped to 63,000 in 1929 and kept falling during the Depression years of the 1930s. The ORT even had to stop paying pensions to retired members because of less money from dues.

By the start of World War II, ORT membership was around 40,000. Railroad telegraphers often had several jobs. They might be station agents, express agents, and Western Union telegraphers. Each employer paid part of their salary. In 1930, the Railway Express Agency started handling certain shipments. This affected ORT members who worked as express agents. The ORT said the company was breaking agreements about pay.

The ORT took the company to court. After several appeals, the case went to the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1944, the Supreme Court decided in favor of the union. This decision was important. It showed that agreements made through collective bargaining (when the union negotiates for all its members) were more important than individual agreements. It also supported the union's right to negotiate for its members.

Final Years and Mergers

In the 1950s and 1960s, the railroad industry declined. This led to many ORT members losing their jobs. The ORT tried to protect jobs by demanding the right to say no to job cuts. Railroad companies accused them of "featherbedding." This means requiring unnecessary workers.

In 1962, the ORT went on strike against the Chicago & Northwestern Railroad. This was to protest 600 telegraphers being laid off. A special board, set up by President John F. Kennedy, sided with the railroad. They said the layoffs were fair. However, the railroad had to give 90 days' notice to laid-off workers. They also had to pay them 60 percent of their yearly salary for up to five years.

In 1965, the ORT changed its name to the Transportation Communications Employees Union. In 1969, this union joined with another large union called the Brotherhood of Railway & Airline Clerks (BRAC). At the time of this merger, the ORT had about 30,000 members.

In 1985, BRAC decided to bring back the TCU name as the Transportation Communications International Union. In 2005, this "new" TCU joined with the International Association of Machinists.

|