Panama Papers facts for kids

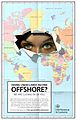

The Panama Papers (also known as Papeles de Panamá in Spanish) are a huge collection of 11.5 million secret documents. These documents, which were first shared on April 3, 2016, show financial and legal information about over 214,000 offshore companies. An offshore company is a business set up in a different country, often one with low taxes and strict privacy rules.

These papers came from a law firm in Panama called Mossack Fonseca. Some of the documents were very old, going back to the 1970s. They contained private financial details about rich people and public officials. While setting up offshore companies can be legal, reporters found that some of Mossack Fonseca's companies were used for illegal things. These included fraud, not paying taxes (called tax evasion), and getting around international rules (called international sanctions).

An anonymous person, known only as "John Doe," leaked these documents to a German journalist. John Doe said they leaked the papers because they saw how much unfairness the documents showed. Because there was so much information, the German newspaper asked the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) for help. Journalists from 107 news groups in 80 countries worked together for over a year to study the documents.

The documents were called the Panama Papers because they came from Panama. However, the government of Panama and others were not happy with this name. They worried it would make their country look bad. Some news groups used the name "Mossack Fonseca papers" instead.

In 2020, German authorities issued arrest warrants for the two people who started the law firm, Jürgen Mossack and Ramón Fonseca. They were wanted for helping with tax evasion and being part of a criminal group. In 2024, 27 former Mossack Fonseca employees, including the founders, went to trial in Panama for money laundering.

Contents

- What the Panama Papers Showed

- Understanding Tax Havens

- How Journalists Worked on the Leak

- Data Security Problems at Mossack Fonseca

- The Impact of the Leak

- People and Groups Named in the Papers

- Mossack Fonseca's Responses

- Responses in Panama

- Global Reactions and Investigations

- FIFA Investigation

- Money Recovered

- Images for kids

- See also

What the Panama Papers Showed

The leaked documents showed information about many important people around the world. This included leaders, politicians, sports stars, and artists. While owning an offshore company is not always against the law, journalists found that some of these companies were used for illegal activities. These activities included fraud, tax evasion, and avoiding international sanctions.

The papers also raised questions about what is morally right. For example, some very wealthy people and companies avoided paying taxes in very poor countries. One company, Octea, owed over $700,000 in property taxes to a city in Sierra Leone, a poor country. This was despite the company making huge amounts of money from exports.

Some of the offshore company dealings described in the documents seemed to break laws, like trade sanctions, or came from political corruption. For example:

- In Uruguay, five people were arrested for laundering money through Mossack Fonseca companies.

- A Swiss lawyer was accused of mismanaging client money and helping rich people and the Qatari royal family hide funds.

The leak named 12 current or former world leaders, 128 other public officials, and hundreds of famous people and business owners from over 200 countries.

Understanding Tax Havens

People and companies might open offshore accounts for many reasons, and some of them are legal. For example, a business might want to keep some of its money in US dollars. Also, planning how your money will be handled after you die (called estate planning) can be a legal way to avoid some taxes.

For example, the famous American filmmaker Stanley Kubrick owned a large English manor. After he died, three companies set up by Mossack Fonseca owned the property. These companies were held by trusts for his children and grandchildren. This arrangement helped his family avoid paying high taxes to both the US and British governments.

Other uses of offshore companies are less clear. Some Chinese companies might set up offshore businesses to get money from other countries, which is usually against the law in China. In some countries with dictators, leaders might use offshore companies to give oil or gold deals to themselves or their families. While this might be legal in their country, it can sometimes be prosecuted under international law.

A tax haven is a country or place where banks mainly serve people or businesses who don't live there. These places usually ask for very little information about who owns the money and have very low taxes.

Many experts believe that tax havens help rich people and large companies avoid paying their fair share of taxes. This means governments, both rich and poor, have less money for important public services like schools and hospitals. Experts also say that these shell companies are often used for large-scale money laundering.

Money laundering also affects richer countries. For example, a popular way to hide money is to buy expensive real estate in places like London, Miami, and New York. This practice can make housing prices go up, making it harder for regular people to afford homes.

Many countries believe that international cooperation is needed to share tax information between tax authorities. Panama, Vanuatu, and Lebanon might be put on a list of countries that don't cooperate enough. This is because they don't follow important rules for sharing banking information.

These rules include:

- Sharing information when asked.

- Signing agreements about information standards.

- Agreeing to automatically share information in the future.

Countries that don't meet these rules could be put on a "blacklist" or "greylist," which means they are seen as not cooperating.

How Journalists Worked on the Leak

The ICIJ helped organize the huge amount of data from the Panama Papers. They worked with reporters from many news organizations around the world, including The Guardian and the BBC. In total, reporters from 100 news groups in 25 languages used the documents.

Security was a big concern. The anonymous leaker, "John Doe," insisted that reporters only communicate using encrypted messages and never meet in person, saying their life was in danger.

The German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung also worried about security for their source, the documents, and their partners in countries with corrupt governments. They stored the data on computers that were never connected to the internet. They even painted the screws on the computers with glitter nail polish to see if anyone tried to tamper with them!

Reporters organized the documents into folders for each company. These folders held emails, contracts, and scanned papers. There were millions of emails, database entries, PDFs, and images.

Journalists used special software to sort and search through all the documents. This helped them find names of people and companies, connect them, and understand how money was moved around.

More stories based on this data were released later, and a searchable database of over 200,000 offshore companies was made public in May 2016. The amount of data in the Panama Papers was much, much larger than previous leaks like WikiLeaks.

Data Security Problems at Mossack Fonseca

Mossack Fonseca told its clients and news sources that their emails had been hacked. They said they always followed the law.

However, data security experts found that the company was not encrypting its emails. They were also using old software with known weaknesses, making it easier for hackers to get in. Their computer network was also not very secure, as their email and web servers were not separated from their client database.

A hacker even claimed they could access the customer database because of a common type of attack called "SQL injection." Another expert later found that Mossack Fonseca's client login page was running several types of spy software, showing many security problems.

The Impact of the Leak

The director of the ICIJ called the Panama Papers "probably the biggest blow the offshore world has ever taken." Edward Snowden, a famous whistleblower, called it the "biggest leak in the history of data journalism."

Some people, like the co-founder of Occupy Wall Street, saw it as a new way for leaks to be handled by professional journalists working together. However, WikiLeaks criticized the ICIJ for not releasing all the documents at once, saying it was "1% journalism."

The whistleblower later said that the murders of journalists Daphne Caruana Galizia and Ján Kuciak (who were investigating the Panama Papers) deeply affected them.

People and Groups Named in the Papers

While offshore companies are not illegal everywhere, reporters found that some Mossack Fonseca companies were used for illegal things. These included fraud, corruption, tax evasion, and avoiding international sanctions.

The reports showed how wealthy people, including public officials, could keep their financial information secret. Initial reports identified five current or former heads of state, as well as officials and close family members of leaders from over forty countries.

Some of the people mentioned included:

- Current leaders like President Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan of the United Arab Emirates and King Salman of Saudi Arabia.

- Former presidents like Mauricio Macri of Argentina and Ahmed al-Mirghani of Sudan.

- Former prime ministers like Bidzina Ivanishvili of Georgia and Ayad Allawi of Iraq.

The leaked files also named 61 family members and close friends of prime ministers, presidents, and kings. This included the brother-in-law of China's leader, children of former prime ministers of Pakistan, and the nephew of former South African president Jacob Zuma. Even the son of former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan and the son of former British prime minister Margaret Thatcher were mentioned.

The documents also showed how money from the famous 1983 Brink's-Mat robbery was hidden through a Panamanian company. The company was set up for an unknown client shortly after the robbery.

The famous actor Jackie Chan was also mentioned as a shareholder in six companies based in the British Virgin Islands.

What Mossack Fonseca Did for Clients

Mossack Fonseca was one of the biggest firms in its field. Banks and other financial institutions often sent clients to them. The firm helped clients set up and manage shell companies in countries with friendly laws. They could create "complex shell company structures" that, even if legal, made it very hard to see who the real owners were.

The leaked papers showed how complicated these structures could be. Mossack Fonseca worked with over 14,000 banks and law firms to set up companies for their clients. Most of these companies were registered in the British Virgin Islands.

The documents also showed that the firm would sometimes change the dates on documents if clients asked. In 2008, Mossack Fonseca even hired a 90-year-old British man to pretend to be the owner of an offshore company for a US businesswoman. This was a clear violation of rules meant to prevent money laundering.

Clients Who Were Under Sanctions

Many companies and individuals use the secrecy of offshore shell companies to get around international sanctions. Sanctions are rules put in place by countries (like the US) to limit trade or financial dealings with certain people, groups, or countries, often because of their actions.

More than 30 Mossack Fonseca clients were at some point blacklisted by the US Treasury Department. These included businesses linked to important figures in Russia, Syria, and North Korea.

For example, Mossack Fonseca continued to work with six businesses for Rami Makhlouf, a cousin of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad, even though the US had put sanctions on him. Internal documents showed that Mossack Fonseca knew about the sanctions but still worked with him for a while.

The firm also worked with DCB Finance, a company linked to North Korea, despite international sanctions against North Korea's weapons program. The US Treasury Department had called DCB Finance a front company for a North Korean bank that helped sell arms.

Mossack Fonseca, like all banks, was supposed to be careful about clients who were "politically exposed persons" (PEPs) – people who are or have close ties to government officials. This is to prevent money laundering or fraud. However, they sometimes failed to identify such risks.

Mossack Fonseca's Responses

Mossack Fonseca said that while they might have been hacked, nothing in the leaked documents showed they did anything illegal. They stated they had a good reputation for 40 years.

One of the founders, Ramón Fonseca Mora, said the reports were false and full of mistakes. He also said that many people mentioned were never clients of their firm.

Mossack Fonseca suggested that if any laws were broken, the responsibility might lie with other institutions. They said that about 90% of their clients were professional intermediaries, like banks, who were supposed to check their own clients according to anti-money laundering rules.

Jürgen Mossack, the other co-founder, said the leak was not an "inside job" and that the company was hacked by servers from outside Panama.

In March 2018, Mossack Fonseca announced it would close down. They said the Panama Papers scandal had caused "irreversible damage" to their image.

In 2019, a movie based on the Panama Papers called The Laundromat was released on Netflix. Mossack and Fonseca tried to stop the movie, saying it was unfair and could harm their right to a fair trial. However, a judge allowed the movie to be released.

Responses in Panama

When the news first broke, Ramón Fonseca Mora said he was not responsible and had not been accused of anything. He said the firm was a victim of a hack and that he was not responsible for what clients did with the offshore companies, which were legal under Panamanian law.

Panama's government initially felt attacked. The president, Juan Carlos Varela, created a commission to look into their financial system. However, a Nobel Prize winner, Joseph Stiglitz, resigned from this commission because the Panamanian government would not promise to make the final report public.

Panama's officials strongly denied that Panama was a tax haven and said the country would not be a "scapegoat." They also said the publication of the papers was an attack on Panama because of its strong economy.

Panamanian lawyers and business groups called the leak "cyber bullying" and an attack on Panama's image. They urged the government to sue. They stressed that offshore companies are legal, but illegal activities like money laundering or tax evasion are not.

In October 2016, it was reported that the Panamanian government spent $370 million to "clean" the country's image.

Law Enforcement Actions

Panama's Attorney General's office announced an investigation into Mossack Fonseca. In April 2016, police raided Mossack Fonseca's offices to get documents related to possible illegal activities. They also raided another location and found a lot of evidence.

A government body that supervises financial firms also started a review of Mossack Fonseca to see if they followed tax laws.

However, in January 2017, the investigation against Mossack Fonseca was temporarily stopped because the firm filed a legal appeal.

In February 2017, Mossack and Fonseca were arrested on money-laundering charges.

Global Reactions and Investigations

Many countries around the world reacted to the Panama Papers and started their own investigations.

Australia

Australia announced it would create a public register showing the real owners of shell companies to fight tax avoidance. The Australian tax office started investigating 800 Australians on the Mossack Fonseca client list.

The leaked documents linked some Australian businessmen to mining deals in North Korea, a country under international sanctions. This raised questions about whether Australia's government was doing enough to stop such deals.

Former Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull was also found in the Panama Papers as a former director of a Mossack Fonseca company. He denied any wrongdoing.

New Zealand

New Zealand's tax department began looking into people in the country who might have been involved with Mossack Fonseca. The director of the ICIJ said that New Zealand is known as a tax haven and a "nice front for criminals." This is because New Zealand allows foreign trusts and companies where the real owners can remain secret, and these trusts are not taxed in New Zealand.

New Zealand's Prime Minister John Key said that the whistleblower was confused about New Zealand's role with the Cook Islands, which is also a tax haven.

Niue

Mossack Fonseca helped the tiny island of Niue set up a tax haven in 1996. The law firm wrote the laws, allowing offshore companies to operate in total secrecy. This brought money to the island. However, the US government raised concerns about money laundering, and some banks stopped working with Niue. This caused problems for the local people, so Niue ended its contract with Mossack Fonseca. Still, the Panama Papers database lists nearly 10,000 companies and trusts set up in Niue.

Samoa

Many recently created shell companies were set up in Samoa, perhaps after Niue changed its tax laws. The Panama Papers database lists over 13,000 companies and trusts set up there.

FIFA Investigation

Many people mentioned in the Panama Papers were connected to FIFA, the world's football governing body. This included former football officials and even famous players like Lionel Messi.

The leak showed a conflict of interest involving a member of the FIFA Ethics Committee. Swiss police also searched the offices of UEFA (European football's governing body) after the new FIFA president, Gianni Infantino, was named. He had signed a TV deal with a company that the FBI later accused of bribery. Infantino denied any wrongdoing.

Money Recovered

By April 2019, over $1.2 billion had been recovered globally from lawsuits, fines, and unpaid taxes because of the Panama Papers. Great Britain recovered the most money, followed by Denmark, Germany, Spain, France, and Australia. Investigations are still ongoing in many countries, and more money is expected to be recovered.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Papeles de Panamá para niños

In Spanish: Papeles de Panamá para niños

- Swiss Leaks (2015)

- Paradise Papers (2017)

- Pandora Papers (2021)

- The Laundromat (2019 film)

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |