Parachute Jump facts for kids

|

Parachute Jump

|

|

Seen from the Riegelmann Boardwalk

|

|

| Location | Coney Island, Brooklyn, New York City |

|---|---|

| Built | 1939 |

| Architect | Michael Mario; Edwin W. Kleinert |

| NRHP reference No. | 80002645 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | September 2, 1980 |

The Parachute Jump is an old amusement ride and a famous landmark in Brooklyn, a part of New York City. You can find it along the Riegelmann Boardwalk at Coney Island. This amazing structure is a 250-foot-tall (76 m) steel tower.

Twelve steel arms spread out from the top of the tower. When the ride was working, each arm held a parachute. People sat in two-person canvas seats, were lifted to the very top, and then dropped! Parachutes and special shock absorbers at the bottom made sure they landed safely.

It was first built for the 1939 New York World's Fair in Flushing Meadows–Corona Park, also in New York City. With a flagpole on top, it was the tallest building at the Fair. In 1941, after the Fair, it moved to its current spot in Steeplechase amusement park on Coney Island. The ride stopped working in the 1960s when the park closed. The tower then started to fall apart.

Even though people talked about tearing it down or fixing it, the Parachute Jump stayed unused for many years. Since the 1990s, it has been fixed up several times. These repairs made it safer and look better. In the 2000s, it was fully restored and got a cool new lighting system. The lights were turned on in 2006 and updated again in 2013. Today, it lights up for special events, like remembering important people. The Parachute Jump is the only part of Steeplechase Park that is still standing. It is now a New York City landmark and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Contents

What the Parachute Jump Looks Like

The Parachute Jump is located on the Riegelmann Boardwalk at Coney Island. It stands between West 16th and West 19th Streets. The structure has a six-sided steel frame that sits on a hexagonal base. Each of the tower's legs is a strong column with horizontal and diagonal metal bars. These legs are held firmly by concrete foundations.

There is a ladder on the north side of the tower that goes up from the base. Special devices are in place to stop people from climbing the frame. The tower has about 8,000 lights that create amazing light shows at night. The wide base of the tower makes it very stable, and it gets narrower towards the top.

The Parachute Jump is 250 feet (76 m) tall. When it was at the 1939 New York World's Fair, it was 262 feet (80 m) tall because it had a 12-foot (3.7 m) flagpole on top. At the very top, there are twelve drop points. These are marked by steel arms that reach out 45 feet (14 m) from the center of the tower. Each arm held a parachute.

Eight guide wires hung from each arm to help keep the parachutes open. There were walkways at the top of the tower and along each arm. Real parachutes hung from each of the twelve arms and were kept open by metal rings. Each parachute needed three people to operate its cables.

Riders sat in two-person canvas seats below the closed parachutes. As the riders were pulled up, the parachutes would open. Once they reached the top, a release system would drop them. The parachutes would slow their fall, and the seats would stop about 4 feet (1.2 m) above the ground. Shock absorbers, which were like big springs, made the landing soft.

The base of the tower has a two-story building called a pavilion. The top floor held the machines that lifted the parachutes. The ground floor had ticket booths and a waiting area. The pavilion has six sides with colorful red, yellow, and blue walls on the upper floor. A concrete platform surrounds the pavilion, which was originally where riders landed.

Because of its shape, the Parachute Jump is sometimes called the "Eiffel Tower of Brooklyn". Some people have said it looks like a giant toy building set or even a mushroom. The Parachute Jump has also appeared in movies, like Little Fugitive (1953).

How the Parachute Jump Came to Be

In the 1930s, people could learn to parachute by jumping from special towers instead of airplanes. A man named Stanley Switlik and George P. Putnam built a 115-foot-tall (35 m) tower in New Jersey. This tower was meant to train airmen. Famous pilot Amelia Earhart was one of the first to jump from it in 1935.

The idea for the "parachute device" came from retired U.S. Naval Commander James H. Strong and Stanley Switlik. Strong had seen simple wooden towers used to train paratroopers in the Soviet Union. Strong designed a safer version with eight guide wires around the parachute. He got a patent for his invention in 1935.

Strong built test platforms at his home in New Jersey. These military towers would drop a single person in a harness, giving them a few seconds of free fall before the parachute opened. When many people wanted to try the ride, Strong changed his design for fun, non-military use. He added a seat for two people, a bigger parachute for a slower drop, and springs to make the landing smoother. This new amusement ride was sold as a 150-foot-tall (46 m) jump with two arms.

Strong sold military versions of his tower to armies around the world. He also turned an observation tower in Chicago's Riverview Park into a six-chute amusement ride called "Pair-O-Chutes." This ride was so popular that Strong asked to build one at the 1939 New York World's Fair. Another jump, also designed by Strong, was built in Paris in 1937.

The Parachute Jump in Action

At the 1939 World's Fair

Construction of the Parachute Jump for the 1939 World's Fair began in December 1938. It was located in the "Amusement Zone" near Meadow Lake in Flushing Meadows–Corona Park, Queens. The candy company Life Savers helped pay for the ride.

The Jump opened on May 27, 1939, about a month after the Fair officially started. It had twelve parachute bays, but only five were ready at first. Eventually, eleven parachutes were used. A 12-foot (3.7 m) flagpole was added to the top of the 250-foot (76 m) tower. This was done to make it taller than a statue in the Soviet Pavilion, after people complained that the Soviet statue was higher than the American flag.

Each ride cost 40 cents for adults and 25 cents for children. The trip to the top took about a minute, and the drop lasted 10 to 20 seconds. The Fair's guidebook called the Parachute Jump "one of the most spectacular features" and said it was like "training for actual parachute jumping." It became the second most popular attraction at the Fair.

A few small problems happened in the first few months. In July 1939, a couple got stuck in the air for five hours because of tangled cables. The mayor of New York City, Fiorello La Guardia, even congratulated them for being brave. Other people also got stuck, but everyone was always brought down safely.

The Parachute Jump's popularity was affected because it was in a hidden part of the Fair. After Life Savers stopped sponsoring it, the ride was moved closer to the subway entrance for the 1940 season. This cost $88,500. Moving the ride helped improve business for the Fair. The Parachute Jump reopened in June 1940. During this time, a couple even got married on the Parachute Jump! When the Fair ended in October, there were plans to move the Parachute Jump to either Coney Island or Palisades Amusement Park in New Jersey.

Moving to Steeplechase Park

Frank Tilyou and George Tilyou Jr., who owned Steeplechase Park, bought the Jump for $150,000. Their park was recovering from a fire in 1939 that had destroyed many big rides. The Parachute Jump was taken apart and moved to the spot where a roller coaster used to be, right next to the boardwalk. Because the new location was windier, the ride needed some changes, like deeper foundations. Engineers Edwin W. Kleinert and Michael Mario oversaw the move.

The Jump reopened in May 1941. At first, unlimited rides on the Parachute Jump were included in Steeplechase Park's entrance fee. Later, they offered "combination tickets" that included park entry and a certain number of rides. During World War II, when many city lights were turned off for safety, the ride stayed lit to help ships navigate. The parachutes were originally colorful, but by the mid-1940s, they were replaced with white ones. The tower was repainted every year.

The Parachute Jump attracted up to half a million riders each year. Most riders reached the top in less than a minute, and the drop took 11–15 seconds. It felt like "flying in a free fall." The ride was very popular with military personnel. Sometimes, riders would get stuck or tangled, but they were always helped down. The ride had to close on windy days, especially when winds were stronger than 45 mph (72 km/h). Also, it needed at least fifteen people to operate, which made it expensive to run.

Coney Island became less popular in the 1960s due to more crime, not enough parking, and bad weather. Another World's Fair in 1964 also drew people away from Steeplechase Park. On September 20, 1964, Steeplechase Park closed for good. The land was sold to a developer named Fred Trump. He wanted to build a large dome with fun activities and a convention center on the site.

The Ride Closes

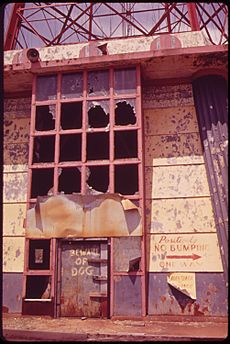

The Parachute Jump stopped working when Steeplechase Park closed in 1964. Some sources say it might have operated until 1968, but many historians believe it closed in 1964. A newspaper article in 1965 said the Parachute Jump was not working and had lost its wires and parachutes. Another article in 1966 even suggested turning it into the "world's largest bird feeding station."

However, some reports from the 1970s and later still mention a 1968 closing date. The city's Parks Department also says it closed in 1968, as it was one of several smaller rides that continued to operate for a short time after the main park closed.

After the Closure

City Takes Over

In 1966, local groups asked the city to make the Parachute Jump an official landmark. However, Fred Trump, who owned the land, wanted to sell the tower for scrap metal. He didn't think it was old enough to be a landmark. For a while, Trump rented out the base area for a small go-kart track. In 1968, the city decided to buy the land where Steeplechase Park used to be for $4 million.

The Parachute Jump then became the responsibility of NYC Parks. The agency tried to sell the Jump in 1971 but no one wanted to buy it. NYC Parks planned to tear it down if no one bought it. But a study in 1972 found that the Jump was still strong. At that time, people suggested making it a landmark and adding a light show.

The city tried to turn the Steeplechase site into a state park, but it didn't work out. By the late 1970s, the city wanted to build an amusement park there. A man named Norman Kaufman, who ran some small rides on the site, wanted to reopen the Parachute Jump. But Kaufman was removed from the site in 1981, and his plan ended.

Becoming a Landmark

After it was abandoned, the Jump became a place where teenagers would climb, and its base was covered in graffiti. Even though it was falling apart, it was still important to the community. People said you could see the tower from up to 30 miles (48 km) away. Local groups wanted to save the structure. In July 1977, the city officially named the tower a landmark. However, three months later, another city board disagreed, saying they weren't sure if the tower was strong enough. Despite this, the Parachute Jump was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.

The city government was worried about the tower's safety. A study in 1982 said it would cost $500,000 to make the ground under it stable and another $1 million to make it work again. Demolishing the structure would cost at least $300,000, which was also expensive. The cheapest option was just to maintain it, which would cost $10,000 a year.

The NYC Parks commissioner, Henry Stern, said the Parachute Jump was a "totally useless structure" and didn't think it could ever work as a ride again. He said that even the Eiffel Tower had a restaurant. Stern welcomed ideas from the community, but other officials thought the plans, like turning it into a giant windmill, were unrealistic. In the mid-1980s, a restaurant owner named Horace Bullard suggested rebuilding Steeplechase Park and making the Parachute Jump work again. At that time, the Parachute Jump was seen as a "symbol of despair" because no one had really tried to fix it.

In 1987, the city held meetings to decide if the Parachute Jump, Wonder Wheel, and Coney Island Cyclone should be landmarks. Two years later, on May 23, 1989, the Parachute Jump officially became a city landmark again. After this, Bullard was allowed to develop his amusement park, which included reopening the Parachute Jump. But these plans were delayed because there wasn't enough money.

Fixing and Lighting the Jump

In 1991, the city announced it would spend $800,000 to keep the Jump from falling down, even though they didn't have enough money in their budget. The city made the structure stable in 1993 and painted it in its original colors. However, it still rusted because of the salty air. A thrill-ride company was asked to see if the Parachute Jump could work again. Bullard's plan for the park was in conflict with another idea to build a baseball stadium on the site. Bullard's deal fell through in 1994. The area north of the Parachute Jump became a baseball stadium, KeySpan Park (now MCU Park), which opened in 2000.

The New York City Economic Development Corporation (NYCEDC) took over the tower in 2000. At first, the city wanted to make it a working ride again. But this plan was dropped because it would cost too much money to make it safe. The repairs would have cost $20 million, plus very high insurance costs.

2002 Restoration and First Lights

A $5 million restoration project started in 2002 and lasted 18 months. The NYCEDC hired an engineering company to fix the structure. The top part of the tower was taken apart, and about two-thirds of the original structure was removed and replaced. The tower was painted red. The restoration finished around July 2003. After the project, the Brooklyn Borough president, Marty Markowitz, started looking for ideas to use or reopen the structure. In 2004, a lighting company was hired to design a night-time lighting plan for the Parachute Jump. This lighting project cost $1.45 million.

In 2004, a design contest was held to find ideas for the 7,800-square-foot (720 m²) pavilion at the Jump's base. More than 800 teams from 46 countries took part. The winning design suggested a bowtie-shaped pavilion with lights and an activity center for all seasons. This center would include a souvenir shop, restaurant, bar, and exhibition space.

The first night-time light show happened on July 7, 2006. The lights could create six different animations and used most colors except green, which wouldn't show up well on the red tower. The animations were based on local events, like the boardwalk's seasons, the moon's cycle, the Coney Island Mermaid Parade, and holidays like Memorial Day and Labor Day. There was also a "Kaleidoscope" sequence for other holidays. The lights were usually on from dusk until midnight in summer, and until 11:00 p.m. the rest of the year. To help protect birds, the tower lights turned off at 11:00 p.m. during bird migration seasons.

2013 Restoration and New Lights

Even though Markowitz liked the first light show, by 2007 he was already planning a "Phase I" for a bigger lighting upgrade. In February 2008, the city started planning the second phase of lights. In 2010, anti-climbing devices were put on the Parachute Jump after people kept trying to climb it. The lights were temporarily turned off in 2011 because they weren't being maintained. At the same time, the area around the tower was redeveloped into Steeplechase Plaza.

A $2 million renovation was finished in 2013. After this, the tower had 8,000 LED lights, much more than the 450 lights from the first installation. The B&B Carousell, an old carousel, was moved to Steeplechase Plaza next to the Parachute Jump in 2013. The tower was lit up for its first New Year's Eve Ball drop at the end of 2014, and it has been lit for New Year's Eve every year since. The Parachute Jump also lights up for special causes, like World Autism Awareness Day and Ovarian Cancer Awareness Month. It also lights up to remember famous people, like after the 2020 death of basketball player Kobe Bryant.