Peace of Augsburg facts for kids

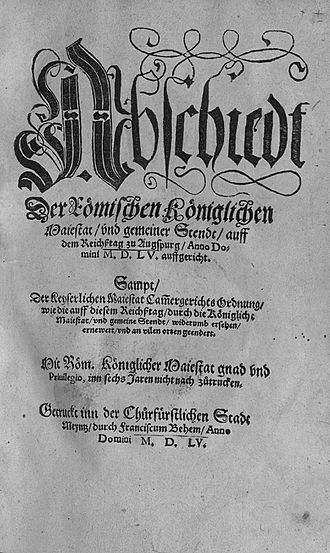

The front page of the document. Mainz, 1555.

|

|

| Date | 1555 |

|---|---|

| Location | Augsburg |

| Participants | Charles V, Schmalkaldic League |

| Outcome | (1) Established the principle Cuius regio, eius religio. (2) Established the principle of reservatum ecclesiasticum. (3) Laid the legal groundwork for two co-existing religious confessions (Catholicism and Lutheranism) in the German-speaking states of the Holy Roman Empire. |

The Peace of Augsburg, also known as the Augsburg Settlement, was an important agreement. It was signed in September 1555 in the city of Augsburg. This treaty was made between Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, and a group called the Schmalkaldic League.

The Peace of Augsburg officially ended a big religious fight. It made the split in Christianity permanent within the Holy Roman Empire. This meant that rulers could choose either Lutheranism or Roman Catholicism as the official religion for their state. However, this agreement also led to less Christian unity across Europe. Other Christian groups, like Calvinism, were not allowed until much later.

Many people see the Peace of Augsburg as the first step toward modern independent countries in Europe. The system it created, however, broke down in the early 1600s. This breakdown was one of the reasons for the terrible Thirty Years' War.

Contents

What the Peace of Augsburg Did

The Peace of Augsburg introduced a key idea: Cuius regio, eius religio. This Latin phrase means "whose realm, his religion." It allowed the princes (rulers) of states within the Holy Roman Empire to pick their religion. They could choose either Lutheranism or Catholicism. This choice then became the official religion for everyone in their area.

This rule also meant that if people didn't want to follow their prince's religion, they could move. They were given time to leave and settle in a different region. There, their chosen religion was accepted.

Article 24 of the treaty said: "If our people, whether Catholic or Lutheran, want to leave their homes with their families to live elsewhere, they should not be stopped. They can sell their property after paying local taxes and should not be dishonored."

Before this peace, Emperor Charles V had tried to solve religious differences. He issued something called the Augsburg Interim in 1548. This was a temporary rule about the two religions in the empire. It mostly followed Catholic rules but allowed priests to marry and people to receive both bread and wine during communion. However, Protestant areas didn't like this and created their own rules.

The Interim was overturned in 1552 by a revolt led by the Protestant elector Maurice of Saxony. During talks in Passau in 1552, even Catholic princes wanted a lasting peace. They worried the religious conflict would never end. The emperor, however, didn't want to accept the permanent religious split. The Peace of Passau in 1552 was a step towards the Augsburg Peace. It gave Lutherans religious freedom after Protestant armies won a victory. But this peace was only temporary, until the next big meeting of the empire.

The Peace of Augsburg was negotiated for Charles V by his brother, Ferdinand. It officially recognized Lutheranism within the Holy Roman Empire. This followed the rule of cuius regio, eius religio. Knights and towns that had been Lutheran for a while were protected by something called the Declaratio Ferdinandei.

On the other hand, the Ecclesiastical reservation was another important rule. It stopped the "whose realm, his religion" rule from applying if a church ruler (like a bishop) became Lutheran.

Key Rules of the Peace

The Peace of Augsburg had three main rules:

Whose Realm, His Religion

The first rule was cuius regio, eius religio ("Whose realm, his religion"). This meant that each state would have one religion. The prince's religion (either Lutheranism or Roman Catholicism) became the religion for everyone in that state. People who didn't agree with the prince's religion were allowed to move away. This was a new and important idea in the 1500s. Other Christian faiths, like Calvinism, were not recognized by the Empire.

Church Rulers' Rule

The second rule was called the reservatum ecclesiasticum (ecclesiastical reservation). This rule dealt with special church states. If a church leader (like a bishop or abbot) in charge of a state changed his religion, the people in his state did not have to change theirs. Instead, the church leader was expected to step down from his position. This wasn't fully written in the agreement, but it was the expectation.

Ferdinand's Declaration

The third rule was known as Declaratio Ferdinandei (Ferdinand's Declaration). This rule protected knights and some cities. It meant they didn't have to follow the prince's religion if they had been practicing the reformed religion since the 1520s. This allowed some cities and towns to have both Catholics and Lutherans living together. It also protected the power of noble families, knights, and some cities to decide their own religious rules. Ferdinand added this rule at the very last minute, on his own. This third rule was kept secret for almost 20 years after the treaty was signed.

Unsolved Problems

Even though the Peace of Augsburg brought some peace, it left some problems unsolved. It only recognized Lutheranism and Catholicism. It did not accept other Protestant groups like Calvinism or Anabaptism. This meant that many Protestant groups in the empire were still seen as practicing heresy (beliefs against official church teachings). They were not legally recognized until the Peace of Westphalia in 1648.

The lack of acceptance for Calvinists caused serious problems. These problems eventually led to the terrible Thirty Years' War. One famous event was the Third Defenestration of Prague in 1618. In this event, two officials of the Catholic king of Bohemia were thrown out of a castle window in Prague.

What Happened Next

The rule about church rulers (ecclesiastical reservation) was tested in the Cologne War (1583–1588). This war happened because the ruling church leader, Hermann of Wied, became Protestant. He didn't force his people to convert, but he made Calvinism equal to Catholicism in his area. This caused two big problems: first, Calvinism was still seen as a heresy. Second, the leader didn't step down from his church position. If he stayed, he could vote for the emperor. Also, his marriage raised the chance that his church state could become a family-ruled area. This would change the balance of religious power in the empire.

Another result of the religious troubles was Emperor Charles V's decision to step down. He divided his large empire into two parts. His brother Ferdinand ruled the Austrian lands. Charles's very Catholic son, Philip II, became the ruler of Spain, the Spanish Netherlands, parts of Italy, and other lands overseas.

See also

In Spanish: Paz de Augsburgo para niños

In Spanish: Paz de Augsburgo para niños

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |