Penn Central Transportation Co. v. New York City facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Penn Central Transportation Co. v. New York City |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Argued April 17, 1978 Decided June 26, 1978 |

|

| Full case name | Penn Central Transportation Company, et al. v. New York City, et al. |

| Citations | 438 U.S. 104 (more)

98 S. Ct. 2646; 57 L. Ed. 2d 631; 1978 U.S. LEXIS 39; 11 ERC (BNA) 1801; 8 ELR 20528

|

| Prior history | Appeal from the Court of Appeals of New York |

| Holding | |

| Whether a regulatory action that diminishes the value of a claimant's property constitutes a "taking" of that property depends on several factors, including the economic impact of the regulation on the claimant, particularly the extent to which the regulation has interfered with distinct investment-backed expectations, as well as the character of the governmental action. | |

| Court membership | |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Brennan, joined by Stewart, White, Marshall, Blackmun, Powell |

| Dissent | Rehnquist, joined by Burger, Stevens |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. amend. V | |

Penn Central Transportation Co. v. New York City was an important case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States in 1978. It helped define when a government rule that affects private property should be considered a "taking." A "taking" means the government has to pay the property owner for their loss.

Protecting Historic Buildings in New York City

The New York City Landmarks Law

In 1965, New York City passed a law called the New York City Landmarks Law. This happened because people were worried about losing important old buildings. For example, the beautiful original Pennsylvania Station was torn down in 1963.

The Landmarks Law was created to protect buildings that are special to the city's history or culture. It makes sure these buildings can still be used, but also keeps their important look. The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission is the group that enforces this law.

Railroad Companies Face Challenges

Railroad travel was very popular in the 1920s. But by the late 1930s, fewer people were using trains. World War II brought a short boost in the 1940s. However, after the war, train use dropped sharply again.

This decline caused many railroad companies to struggle financially. They had to find new ways to make money to stay in business.

Grand Central Terminal's Future

Grand Central Terminal is a famous train station in New York City. In 1954, the New York Central Railroad, which owned Grand Central, started thinking about replacing parts of it. They considered building a huge new tower on top.

However, none of these early plans were ever built. For a while, the station was safe from major changes.

The Pan Am Building is Built

In 1958, a plan was made to build a new office building next to Grand Central Terminal. This building, called the Pan Am Building, was finished in 1963. It helped Grand Central make more money from office space. This gave the terminal more time before anyone tried to rebuild it.

Railroad Companies Merge

Even with the new office space, the New York Central Railroad was still losing money. By 1967, it was close to bankruptcy. The Pennsylvania Railroad was in a similar situation.

In 1968, these two big railroad companies merged. They formed a new company called the Penn Central Railroad. Penn Central then looked for ways to make Grand Central Terminal more profitable. They hoped this would save the company.

Plans for a Tower on Grand Central

In 1968, Penn Central revealed two new designs. These designs, made by architect Marcel Breuer, showed tall office buildings. They would be built right on top of Grand Central Terminal.

One design (Breuer I) was a 55-story building. It would float above the existing station, keeping its original look. The second design (Breuer II) would tear down part of Grand Central. This would create a new look for a 53-story office building. Both plans followed the city's building rules.

Landmarks Commission Says No

The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission reviewed Penn Central's plans. On September 20, 1968, they rejected both designs. Penn Central asked for a special permit, but they were denied again.

The Commission explained their reasons. They said the first design, Breuer I, would still ruin the view of Grand Central. They felt the tall tower would make the historic station look tiny. For Breuer II, they said you can't protect a landmark by tearing it down.

The Commission also said that additions must fit the original design. A 55-story tower would "overwhelm" Grand Central. They believed the station and its surroundings were a "great example of urban design." They wanted to protect it in a way that kept its original beauty.

The Commission offered Penn Central "Transfer of Development Rights" (TDRs). This meant Penn Central could sell the right to build tall structures above Grand Central to other developers. Penn Central felt this wasn't enough money for what they were losing.

The Court Case Begins

Penn Central Sues New York City

After the Landmarks Commission said no, Penn Central sued New York City. They argued that the city's rules stopped them from making enough money from their property. They said that because they were a regulated railroad and in bankruptcy, they couldn't just stop using the terminal. Penn Central felt this was like the city "taking" their property rights without paying them fairly.

A lower court agreed with Penn Central. However, the case eventually went to the highest court in New York. That court changed some of the rules. Penn Central then decided to take their case to the Supreme Court of the United States.

The Supreme Court's Decision

At the Supreme Court of the United States, Penn Central changed their argument. They said the city's rules took away their "air rights" above Grand Central. They pointed out that the station was designed to hold a tall building on top.

But the Supreme Court disagreed. They created a new test to decide if a government action is a "taking." The Court looked at how much the rule affected Penn Central financially. They decided that the impact was not severe enough. Penn Central could still use the terminal as a train station and office space. They could still make a "reasonable return" on their investment.

So, the Supreme Court ruled that New York City's rules did not "take" Penn Central's property. Justice William J. Brennan, Jr. wrote that the law did not stop Penn Central from using the terminal as it had been used for 65 years.

Some justices disagreed. They felt it was unfair for Penn Central to bear the entire cost of preserving Grand Central. They thought the city should help pay for the lost opportunity to build on top.

What Happened Next

Penn Central lost the case. By this time, the company was in bankruptcy. They didn't have enough money to keep Grand Central Terminal in good shape. The station started to fall apart.

Eventually, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) took over. They used public money to restore Grand Central Terminal. Today, it is a beautiful and busy landmark once again.

Images for kids

-

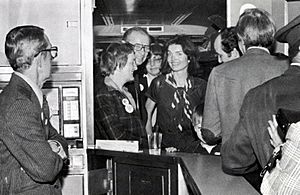

Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis (center) on board the Landmark Express, a special train for the Committee To Save Grand Central Terminal, on April 16, 1978.

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |