Penruddock uprising facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Penruddock Uprising |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

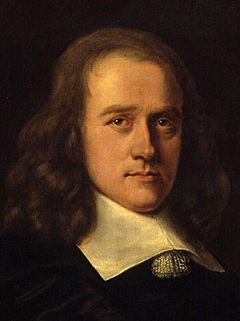

Colonel John Penruddock |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Captain Unton Croke | Colonel John Penruddock; Sir Joseph Wagstaffe | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 60 | 300 to 400 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 8 wounded | Minimal | ||||||

The Penruddock Uprising was a brave attempt by a group called the Royalists to bring back King Charles II to the throne of England. It started on March 11, 1655. This revolt was led by John Penruddock, a landowner from Wiltshire. He had fought for King Charles I during the First English Civil War.

The uprising was meant to be one of many planned revolts happening at the same time. However, the other planned uprisings did not happen. This made it easy for the government to stop Penruddock's group.

Some people thought the revolt was planned by a secret group called the Sealed Knot. But the real organizers were part of a different network. They hoped to get help from other groups who were unhappy with the government. These included Presbyterians, Levellers, and even some soldiers from the New Model Army. However, these hopes did not come true. The government, known as the Protectorate, knew about the plans long before they happened.

Several uprisings were planned across England for March 8. Most of them failed to start. Three days later, Penruddock and Joseph Wagstaffe attacked Salisbury. But since they had no support from other areas, they had to retreat into North Devon. On March 14, a group of New Model Army soldiers, led by Captain Unton Croke, attacked the rebels in South Molton. The rebels quickly gave up.

Even though it failed, the uprising showed that many people did not support the Protectorate. It also showed how much the government relied on its army. Penruddock and 11 others were put to death. But most of the rebels received light punishments. After this, Cromwell started the Rule of the Major-Generals. This made his government even more unpopular.

Why the Uprising Happened

In 1654, people started making plans for a revolt in England. This was supposed to happen at the same time as a rebellion in Scotland. But an attempt to kill Cromwell, called Gerard's conspiracy, failed badly.

After this, a small group of important Royalists, called the Sealed Knot, became responsible for planning future Royalist actions in England. They reported to important exiles like Edward Hyde. One member, Sir Richard Willis, was secretly working for Cromwell's spy chief, John Thurloe. This made the Sealed Knot less effective.

Some Royalists were frustrated because nothing was happening. So, a second group, called the 'Action Party', was formed. This group included landowners and Royalist soldiers from the First English Civil War. John Penruddock was one of them. They started planning another revolt for early 1655. They claimed they had support from important people like Thomas Fairfax, a former army commander. They also thought Levellers and moderate Presbyterians would help.

However, these claims were mostly false. And because Willis was a spy, Cromwell's spymaster, John Thurloe, knew all the details beforehand.

Despite the risks, King Charles II approved the plan. He sent his trusted advisors to help organize it. These advisors were arrested when they arrived in England. But they managed to escape with help from Royalist supporters. They were later joined by the Earl of Rochester, a skilled Royalist cavalry leader. The rebels planned to attack important ports and start revolts in different parts of England.

The Revolt Begins

The Earl of Rochester was joined by Sir Joseph Wagstaffe. Wagstaffe was a professional soldier who had fought in the English Civil War. He was sent to help Penruddock, while Rochester organized the uprising in the north.

Government troops already knew about the plans. They had secured important cities like Hull and Newcastle. On March 8, fewer than 150 men gathered near York. They were quickly scattered by soldiers. Many important Royalists were captured. Rochester managed to escape abroad. Another group of 300 rebels gathered in Nottinghamshire but went home when their leaders did not show up.

The revolt in the west was supposed to distract government troops. This would allow King Charles II to land at Dover. By March 11, Penruddock and Wagstaffe knew that the other uprisings had failed. But they decided to go ahead anyway.

Their first target was Winchester. But they learned its defenses had been strengthened. So, they decided to attack Salisbury instead. They gathered about 150 men. They captured the town and took several prisoners. Wagstaffe wanted to execute a government supporter, but Penruddock stopped him.

The next morning, the rebels left Salisbury. Their numbers had grown to about 400 because they had let prisoners out of local jails. They marched west through Blandford and Sherborne. They reached Yeovil on the evening of March 12. They hoped to be joined by the Marquis of Hertford and thousands of new recruits. But no one showed up. Penruddock then led his small force into Dorset, heading for the Royalist area of Cornwall.

Government troops, led by John Desborough, chased them. On March 14, the rebels crossed into Devon and stopped for the night in South Molton. Around 10 p.m., 60 soldiers from Exeter, led by Captain Unton Croke, attacked them. After a short fight, most of the Royalists gave up. Penruddock was captured. Wagstaffe escaped and made his way to the Spanish Netherlands.

What Happened Next

Penruddock was put on trial in Exeter on April 18, 1655. He argued that opposing Cromwell was not treason. Other legal experts agreed with him. But he was still found guilty. His wife begged Cromwell to spare his life, but Cromwell refused. Penruddock was executed on May 16.

Thirty-two other rebels were sentenced to death. Eleven of them were executed. The rest were sent to Barbados to work as indentured labourers. Seventy of those captured at South Molton were also sent there. They were sold to plantation owners.

One of the most important results of the revolt was Cromwell's reaction. He divided England and Wales into eleven regions. Each region was controlled by a senior army officer with broad powers. This was called the Rule of the Major-Generals. It became very unpopular. It brought together many people who were against Cromwell's government. This achieved something that armed rebellions had failed to do.

Sources