Periodical cicadas facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Periodical cicada |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Specimen of Magicicada septendecim in the Bavarian State Collection of Zoology, Munich (2015) | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hemiptera |

| Family: | Cicadidae |

| Subfamily: | Cicadettinae |

| Genus: | Magicicada W. T. Davis, 1925 |

| Type species | |

| Magicicada septendecim (Linnaeus, 1758)

|

|

A periodical cicada is a special type of insect from the genus Magicicada, found in eastern North America. There are seven different species, famous for their super long life cycles of 13 or 17 years. They are called "periodical" because all the cicadas in one area appear from the ground at the same time, in the same year.

People sometimes call them "locusts," but this is incorrect. Locusts are a type of grasshopper, while cicadas are true bugs, part of the Hemiptera order. For almost their entire lives, periodical cicadas live underground as young insects called nymphs. They drink fluid from the roots of trees.

Then, in the spring of their 13th or 17th year, the nymphs all crawl out of the ground together. They are only active as adults for about four to six weeks. During this short time, the males make loud buzzing songs to find a mate. After mating, females lay eggs in tree branches, and the adult cicadas die. The eggs hatch, and the new nymphs fall to the ground, burrow underground, and start the long cycle all over again.

Contents

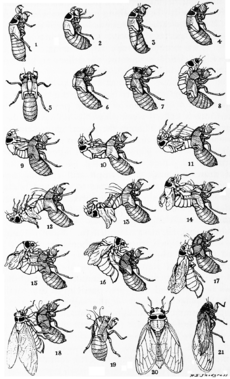

What Do They Look and Sound Like?

The adult periodical cicada has a black body, two big red eyes, and wings that are clear with orange veins. They are usually about 1 to 1.5 inches long, which is a bit smaller than the "annual" cicadas you might see every summer.

Only the male cicadas can "sing." They make a very loud buzzing sound to attract females. Different species have different songs. Some sound like they are calling out "weeeee-whoa" or "Pharaoh." The sound of thousands of cicadas singing together can be as loud as a lawnmower!

Cicadas do not sting and usually do not bite people. They have a mouthpart like a tiny straw, called a proboscis, which they use to drink sap from plants. If you handle a cicada, it might poke you with its proboscis, which can be a little painful but is not dangerous. They are not poisonous and do not spread diseases.

When female cicadas lay their eggs, they cut small slits into the twigs of trees. This can damage very young trees, but older, mature trees are usually not harmed by it.

The Amazing 17-Year Life Cycle

Periodical cicadas have one of the longest life cycles of any insect. Most of their life, either 13 or 17 years, is spent underground as a nymph. In comparison, the cicadas we see every summer (called annual cicadas) have life cycles that are much shorter, usually between two and ten years.

Life Underground

As nymphs, periodical cicadas live about two feet under the surface. They use their straw-like mouths to feed on juices from tree roots. They go through five stages of growth, called instars, while underground. It's believed that the main difference between a 13-year and a 17-year cicada is how long the second instar stage lasts.

Emerging from the Ground

In the spring of their final year, the mature nymphs build tunnels to the surface. They wait until the soil gets warm enough, about 64°F (18°C). Then, on a spring evening, they all crawl out of the ground at once. Sometimes, they emerge in huge numbers—more than a million in a single acre!

The nymphs climb up trees, walls, or anything vertical they can find. They then go through their final molt, shedding their nymph skin (called an exuviae) to become a winged adult. At first, they are soft and white, but their bodies and wings harden and darken within a few hours.

Adult Life and Reproduction

Adult periodical cicadas only live for a few weeks. Their main purpose is to reproduce. The males gather in large groups called choruses and sing together to attract females. When a female is ready to mate, she flicks her wings in a special way to signal a male.

After mating, the female lays her eggs. She cuts V-shaped slits in small tree branches and lays about 20 eggs in each slit. A single female can lay 600 eggs or more. About six to ten weeks later, the eggs hatch. The tiny new nymphs drop to the ground, burrow into the soil, and begin their own 13 or 17-year journey.

-

Mud turrets that emergent Brood X Magicicada nymphs created in Potomac, Maryland (2021)

-

A newly molted adult Brood XIII Magicicada and its old skin in Highland Park, Illinois (2007)

-

An adult Brood X Magicicada septendecim in Princeton, New Jersey (2004)

-

A Brood X Magicicada laying eggs in a tree branch near Baltimore, Maryland (2021)

A Clever Survival Plan

Why do so many cicadas emerge at once? It's a survival strategy called predator satiation. When millions of cicadas appear, predators like birds, squirrels, and cats can eat as many as they want, but there are still too many cicadas for them to eat them all. This ensures that most of the cicadas survive long enough to reproduce.

The Prime Number Mystery

Scientists have wondered why their life cycles are prime numbers (13 and 17). A prime number can only be divided by 1 and itself. One popular theory is that this helps them avoid predators.

Imagine a predator that has its own population boom every 3 years. If the cicadas emerged every 12 years, the predator would be at its peak every time the cicadas appeared (3, 6, 9, 12). But because the cicadas emerge every 17 years, the predator's cycle won't line up as often. This makes it harder for predators to rely on cicadas as a regular food source.

Another idea is that the prime-numbered cycles prevent different broods from emerging at the same time and mating with each other. This helps keep the 13-year and 17-year species separate.

What Are Cicada Broods?

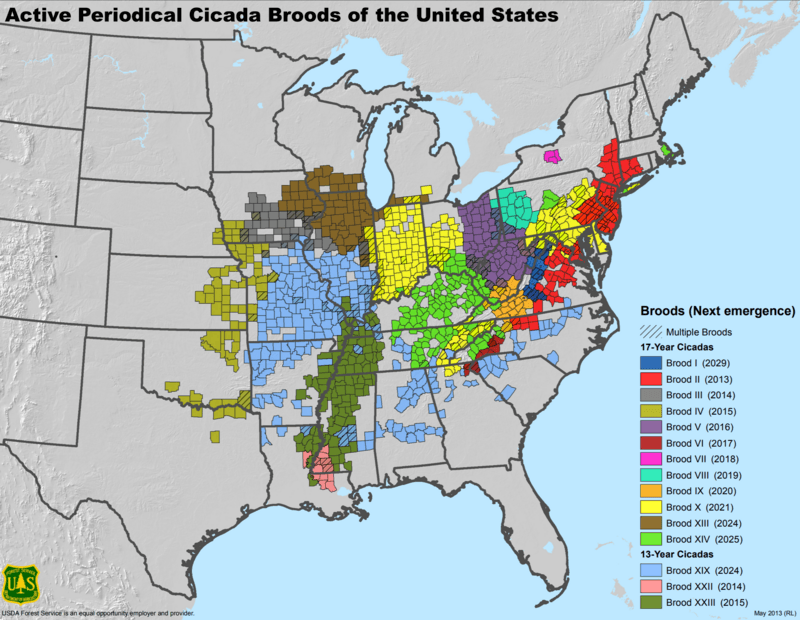

Periodical cicadas are grouped into broods. A brood is a group of cicadas that all emerge in the same year and in the same geographic area. Each brood is given a Roman numeral. Broods I through XVII are on a 17-year cycle, and broods XVIII through XXX are on a 13-year cycle. Today, only about 15 of these broods are known to still exist.

In 2024, two broods emerged at the same time for the first time since 1803: Brood XIII (a 17-year brood) and Brood XIX (a 13-year brood). They mostly appeared in different parts of the Midwest but may have overlapped in a few areas in Illinois. The next time these two specific broods emerge together will be in the year 2245.

| Name | Nickname | Cycle (yrs) | Last emergence | Next emergence | Extent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brood I | Blue Ridge brood | 17 | 2012 | 2029 | Western Virginia, West Virginia |

| Brood II | East Coast brood | 17 | 2013 | 2030 | Connecticut, Maryland, North Carolina, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Virginia, District of Columbia |

| Brood III | Iowan brood | 17 | 2014 | 2031 | Iowa |

| Brood IV | Kansan brood | 17 | 2015 | 2032 | Eastern Nebraska, southwestern Iowa, eastern Kansas, western Missouri, Oklahoma, north Texas |

| Brood V | 17 | 2016 | 2033 | Eastern Ohio, Western Maryland, Southwestern Pennsylvania, Northwestern Virginia, West Virginia, New York (Suffolk County) | |

| Brood VI | 17 | 2017 | 2034 | Northern Georgia, western North Carolina, northwestern South Carolina | |

| Brood VII | Onondaga brood | 17 | 2018 | 2035 | Central New York (Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, Ontario, Yates counties) |

| Brood VIII | 17 | 2019 | 2036 | Eastern Ohio, western Pennsylvania, northern West Virginia | |

| Brood IX | 17 | 2020 | 2037 | southwestern Virginia, southern West Virginia, western North Carolina | |

| Brood X | Great eastern brood | 17 | 2021 | 2038 | New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, District of Columbia, Virginia, West Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, Kentucky, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan |

| Brood XI | 17 | 1954 | Extinct | Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island. Last seen in 1954 in Ashford, Connecticut along the Fenton River | |

| Brood XIII | Northern Illinois brood | 17 | 2024 | 2041 | Northern Illinois and in parts of Iowa, Wisconsin, and Indiana |

| Brood XIV | 17 | 2025 | 2042 | Southern Ohio, Kentucky, Tennessee, Massachusetts, Maryland, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, northern Georgia, Southwestern Virginia and West Virginia, and parts of New York and New Jersey | |

| Brood XIX | Great Southern Brood | 13 | 2024 | 2037 | Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Indiana, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Missouri, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia |

| Brood XXI | Floridian Brood | 13 | 1870 | Extinct | Last recorded in 1870, historical range included the Florida panhandle |

| Brood XXII | Baton Rouge Brood | 13 | 2014 | 2027 | Louisiana, Mississippi |

| Brood XXIII | Mississippi Valley Brood | 13 | 2015 | 2028 | Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Missouri, Mississippi, Tennessee |

Map of Brood Locations

Species and Their History

There are seven known species of periodical cicadas. Three of them have a 17-year life cycle, and four have a 13-year life cycle. Even though they have different cycles, species from each group can look and sound very similar to one another.

Scientists believe that the 13- and 17-year life cycles evolved at least eight different times over the last 4 million years. This likely happened as a way for different groups of cicadas to avoid mating with each other, which helped them develop into separate species over time. This process is called allochronic speciation, where new species form because groups are separated by time.

Where Do They Live?

The 17-year cicadas are mostly found in the northern states, from the East Coast across the Ohio Valley and into the Great Plains. The 13-year cicadas are mostly found in the southern and Mississippi Valley states.

In some places, their territories overlap. For example, Brood IV (17-year) and Brood XIX (13-year) both live in parts of Missouri and Oklahoma.

A Part of History

The first known written report of a major cicada emergence in America was in 1633 by William Bradford, the governor of the Plymouth Colony. He described a "numerous company of Flies" that came out of the ground and made a "constant yelling noise."

In the 1700s, naturalist Pehr Kalm studied the cicadas in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. He was the first to formally report that they appeared every 17 years. Based on Kalm's work, the famous scientist Carl Linnaeus gave the 17-year cicada its scientific name, Cicada septendecim, in 1758. "Septendecim" is Latin for seventeen.

Later, in the 1800s, scientists discovered that some cicada broods in the South had a shorter, 13-year cycle.

Can People Eat Cicadas?

Yes, periodical cicadas are edible. For people who are not allergic to shellfish (like shrimp), cicadas can be a source of food. Some recipes suggest cooking them right after they have molted, while they are still soft.

Native Americans have historically eaten cicadas, often by roasting or frying them. While eating insects might seem strange to some, cicadas are clean eaters. As nymphs, they only drink plant sap, making them a perfectly fine food source.

Images for kids

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |