Phan Đình Phùng facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Phan Đình Phùng

潘廷逢 |

|

|---|---|

A statue of Phan Đình Phùng located in center of the traffic circle facing the Chợ Lớn General Post Office, District 5, Ho Chi Minh City.

|

|

| Born | 1847 Đông Thái, Hà Tĩnh Province, Nguyễn Empire

|

| Died | January 21, 1896 (aged 48–49) Nghệ An Province, Annam

|

| Other names | Phan Đình Phùng |

| Organization | Nguyễn dynasty |

| Movement | Cần Vương |

| Awards | 1st place, Metropolitan imperial examinations, 1877 |

| Notes | |

|

Imperial Censor of Emperor Tự Đức

|

|

Phan Đình Phùng (1847–1896) was a brave Vietnamese leader. He fought against the French who were taking over Vietnam. He was a very important scholar who led military groups against the French in the 1800s. After he died, people in the 1900s called him a national hero.

Phan Đình Phùng was known for his strong will and beliefs. He never gave up, even when the French destroyed his family's tombs. They also arrested his family and threatened to kill them. But Phan Đình Phùng still refused to surrender.

He was born into a family of mandarins (government officials) in Hà Tĩnh Province. Following his family's tradition, he became the best student in the main imperial exams in 1877. Phan quickly moved up in the government under Emperor Tự Đức of the Nguyễn dynasty. He was known for being honest and fighting against corruption.

Phan became the Imperial Censor. This job allowed him to criticize other officials and even the emperor. As the head of this group, Phan's investigations led to many corrupt or bad officials being removed from their jobs.

Contents

Early Life and Government Work

Phan Đình Phùng was born in Đông Thái village in Hà Tĩnh Province. This village was famous for producing many high-ranking government officials. Twelve generations of Phan's family had been successful mandarins. All three of Phan's adult brothers also passed the imperial exams and became officials.

Even though Phan didn't always like the old-fashioned school subjects, he worked hard. He passed the regional exams in 1876 and then came in first in the main exams the next year. In his exam, Phan mentioned Japan as an example of how an Asian country could quickly improve its military.

Phan was known more for his honesty than his school smarts. This helped him rise quickly under Emperor Tự Đức. He first worked as a district official in Ninh Binh Province. There, he punished a Catholic priest who was bothering non-Catholics. Phan was later moved to the capital city of Huế.

As a member of the censorate, Phan watched over other officials. He upset many colleagues by showing that most of them were not practicing rifle shooting as the emperor had ordered. Emperor Tự Đức then sent Phan to inspect northern Vietnam. His report caused many corrupt or bad officials to be removed, including the viceroy (a high-ranking governor) of the northern region. Phan became the Imperial Censor, which allowed him to criticize other high officials and even the emperor. He openly criticized Tôn Thất Thuyết, a very powerful official, because he thought Thuyết was reckless and dishonest.

Fighting for Independence

When Emperor Tự Đức died in 1883, Phan almost died in a power struggle. The regent Tôn Thất Thuyết ignored Tự Đức's wishes for who should be the next emperor. Three emperors were removed and killed in just over a year. Phan protested against Thuyết's actions. He lost his titles and was briefly jailed before being sent away to his home province.

At this time, France had taken over Vietnam and made it part of French Indochina. Phan, along with Thuyết, organized rebel armies. This was part of the Cần Vương movement, which means "Aid the King Movement." Their goal was to kick out the French and put the young Emperor Hàm Nghi in charge of an independent Vietnam. This fight lasted three years until 1888. That's when the French captured Hàm Nghi and sent him away to Algeria.

The Cần Vương Movement

Phan joined the cause of the young Emperor Hàm Nghi after a royal uprising failed in Huế in 1885. Thuyết had already decided to put Hàm Nghi at the head of the Phong Trào Cần Vương. Phan helped by setting up bases in Hà Tĩnh and creating his own guerrilla army.

The Cần Vương revolt began on July 5, 1885. Thuyết launched a surprise attack against the French forces. When the attack failed, Thuyết took Hàm Nghi north to a mountain base. The emperor then issued the Cần Vương edict, calling for people to help the king.

Phan gathered support from his home village and set up his headquarters on Mount Vũ Quang. Phan's group became a model for future rebels. He divided his area into twelve districts for better organization. His forces were disciplined and wore uniforms. Phan first used local scholars as his military leaders. Their first attack was on two nearby Catholic villages that had helped the French. French troops arrived quickly and forced the rebels to retreat. Phan escaped, but his older brother was captured by a former viceroy who was now working with the French.

The French tried to make Phan surrender by threatening his family. They used an old friend to appeal to Phan's feelings and his family traditions. Phan was reported to have replied:

(English)

From the time I joined with you in the Cần Vương movement, I determined to forget the question of family and village.

Now I have but one tomb, a very large one, that must be defended: the land of Vietnam.

I have only one brother, very important, that is in danger: more than twenty million countrymen.

If I worry about my own tombs, who will worry about defending the tombs of the rest of the country?

If I save my own brother, who will save all the other brothers of the country?

There is only one way for me to die now.

This event and Phan's answer showed his deep patriotism. He cared more about his country than his own family or region.

Guerrilla Warfare and Challenges

Phan's men were well-trained. Their military inspiration came from Cao Thắng, a bandit leader whom Phan's brother had protected earlier. They operated in the provinces of Thanh Hóa, Hà Tĩnh, Nghệ An, and Quảng Bình. Their strongest areas were the two central provinces.

In 1887, Phan realized his tactics were wrong. He ordered his men to stop open combat and use guerrilla tactics instead. His men built a network of base camps, food hiding spots, and spy contacts. Phan traveled north to coordinate plans with other leaders. Meanwhile, Cao Thắng led about 1,000 men with 500 firearms. Cao Thắng even made about 300 rifles by taking apart and copying French weapons. French officers later said these copied weapons were well-made.

The rebels' weapons were much weaker than the French ones. They could not get much help from China or other European countries. So, Phan had to find ways to get weapons from Siam by land. He told his followers to create a secret route from Hà Tĩnh through Laos into northeastern Siam. It's unclear if Phan went to Thailand himself, but a young female supporter named Co Tam bought weapons for him in Thailand.

After the Cần Vương Movement

In 1888, Emperor Hàm Nghi was betrayed and captured. He was then sent away to Algeria. Phan and Cao Thắng continued fighting in the mountains of Hà Tĩnh, Nghệ An, and Thanh Hóa. They built 15 more bases to support their main headquarters. Local villagers funded their operations by paying taxes in silver and rice. Phan's men also sold cinnamon bark to raise money.

When Phan returned in 1889, his first order was to find Ngọc, the man who betrayed Hàm Nghi. When Ngọc was found, Phan personally executed him. Phan then launched small attacks on French bases in 1890, but these didn't decide anything. The French built more forts, trying to surround the rebels.

In 1892, a big French attack in Hà Tĩnh failed. In August, Cao Thắng led a bold counterattack on the provincial capital. The rebels broke into the prison and freed their friends. This made the French increase their efforts against Phan. They forced the rebels back into the mountains. Two of their bases fell, and French pressure began to cut off their links with lowland villages. This made it harder to get food, supplies, and new recruits.

In mid-1893, Cao Thắng suggested a big attack on the provincial capital of Nghệ An. Phan reluctantly approved the plan. The troops were eager, but after taking over several small posts, the main force got stuck attacking a French fort. Cao Thắng was badly wounded while leading a risky attack and died. Phan considered the loss of Cao Thắng a very big one.

Phan knew that he might not win in the end. But he believed it was important to keep fighting the French. This showed the people that there was another way besides giving up.

Phan's Final Stand and Legacy

Hoàng Cao Khải, a Vietnamese official working for the French, understood Phan's goals better than the French themselves. Khải was from the same village as Phan. He led a strong effort to crush Phan's forces using all possible methods. By late 1894, relatives and suspected supporters of the rebels were threatened. More rebel commanders were killed. Communications were cut off, and the rebel hiding places became unsafe. To force Phan to surrender, the French arrested his family and dug up the tombs of his ancestors. They publicly displayed the remains in Hà Tĩnh.

Khải sent a message to Phan through a relative. Phan sent a written reply. Khải reminded Phan of their shared origins and promised an amnesty if Phan surrendered. Khải praised Phan's loyalty to the monarchy.

Phan's reply was very strong. He spoke about Vietnam's long history of fighting off invaders like the Chinese dynasties. He asked why a country "a thousand times more powerful" could not take over Vietnam. Phan said it was "because the destiny of our country has been willed by Heaven itself."

Phan blamed the French for the suffering of the people. He said they "acted like a storm." Phan's message was a clear attack on Khải and other Vietnamese who helped the French. He raised the stakes from family and village to the entire nation.

In July 1895, French commanders brought in 3,000 troops to surround the three remaining rebel bases. The rebels could still ambush at night, but Phan got dysentery (a serious illness). He had to be carried on a stretcher when his unit moved. A Vietnamese official named Nguyễn Thân, who helped the French, worked to cut off the rebels from their village supporters. Without supplies, the rebels had to eat roots and dried corn.

Phan died of dysentery on January 21, 1896. His captured followers were executed. A French report said that "the soul of resistance to the protectorate was gone."

Legacy

Phan's body was disturbed after his death. Ngô Đình Khả, a Catholic official who worked for the French, had Phan's tomb dug up. He used Phan's remains in gunpowder to execute other revolutionaries.

Phan Đình Phùng is widely seen as a revolutionary hero in Vietnam. Phan Bội Châu, a leading anti-colonial figure in the early 1900s, greatly praised Phan in his writings. He especially admired Phan's defiance. Hồ Chí Minh, a famous Vietnamese revolutionary leader, also spoke about Phan in the 1940s to gain support for his independence movement. Like Phan, Hồ was from the same region.

Hồ's Viet Minh group even named their self-made grenades after Phan. Since then, Vietnamese communists have presented themselves as the modern versions of respected nationalist leaders like Phan, who fought for Vietnam's freedom. Both North and South Vietnam named important streets in their capital cities after Phan to honor him.

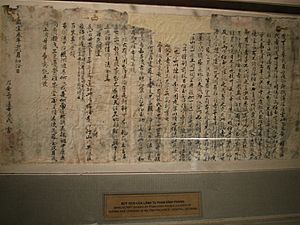

Images for kids

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |